Jason Barker & Hoduk Hwang in Sidecar:

On 3 December, the thirteenth President of the Republic of Korea, Yoon Suk Yeol, declared martial law. Looking tired and frustrated in his televised address to the nation (it is rumoured that he may have been drinking), he justified this decision by accusing the parliamentary opposition of establishing a ‘legislative dictatorship’, ‘conspiring to incite rebellion by trampling on the constitutional order of the free Republic of Korea’ and colluding with ‘North Korean communist forces’. The state of emergency didn’t last long – all of six hours, in which opposition leader Lee Jae-myung and his fellow lawmakers wrestled through a police cordon at the National Assembly and barricaded themselves inside, where they unanimously voted down the presidential decree. They were supported by a large crowd of Seoul residents who had rushed to parliament, forming a human shield to ward off paratroopers wielding assault rifles.

Yoon appeared on television again and agreed to revoke the measures, of which he evidently had not informed South Korea’s closest ally, the US. On 14 December he was impeached by the National Assembly; the constitutional court is deciding whether to remove him from office. The public has breathed a sigh of relief, and the liberal opposition, headed by the Democratic Party, has proclaimed that democracy has been saved. But the episode reveals a striking feature of South Korean political culture: the centrality of anti-communism to the constitutional order. It is in this context that Yoon’s apparent act of madness should be understood.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

At first it seemed that we were doomed to bear witness to a grim spectacle, a media frenzy over the appalling details of a nauseating crime that left its victim, in her own words, “

At first it seemed that we were doomed to bear witness to a grim spectacle, a media frenzy over the appalling details of a nauseating crime that left its victim, in her own words, “ It has been a ghastly year for American women — at least those of us who are not looking forward to being ruled by a claque of cartoon chauvinists — but a pretty rich year for women in the movies. One of 2024’s biggest hits featured an unfairly maligned woman who channels her galvanic anger into a fight against fascism. (I’m talking, of course, about “Wicked.”) Demi Moore gave a scenery-chewing performance in “The Substance,” a gruesome body horror film about the pressure on women to stay nubile. Amy Adams starred in Marielle Heller’s supernaturally inflected “Nightbitch,” in which a woman starts to go feral, perhaps literally, amid the tedium of early motherhood. Mikey Madison was incandescent as a street-smart sex worker from a post-Soviet country in “Anora,” a movie that takes the silly Cinderella fantasy behind “Pretty Woman” and explodes it.

It has been a ghastly year for American women — at least those of us who are not looking forward to being ruled by a claque of cartoon chauvinists — but a pretty rich year for women in the movies. One of 2024’s biggest hits featured an unfairly maligned woman who channels her galvanic anger into a fight against fascism. (I’m talking, of course, about “Wicked.”) Demi Moore gave a scenery-chewing performance in “The Substance,” a gruesome body horror film about the pressure on women to stay nubile. Amy Adams starred in Marielle Heller’s supernaturally inflected “Nightbitch,” in which a woman starts to go feral, perhaps literally, amid the tedium of early motherhood. Mikey Madison was incandescent as a street-smart sex worker from a post-Soviet country in “Anora,” a movie that takes the silly Cinderella fantasy behind “Pretty Woman” and explodes it. Graceland. I am here, for the first time, for the forty-fifth anniversary of Elvis Presley’s death. The name does not feel apt. Surrounded by sweaty, mutton-chopped worshippers in shiny polyester jumpsuits, women with wrinkly tattoos, and little boys in capes, I gulp down hot, syrupy banana glopped with peanut butter on smashed Bunny Bread to condition myself, then set out to meet the fans who keep a dead man alive as an engine of consumerism, a weird religion, and an inexplicable (to me) lifelong obsession.

Graceland. I am here, for the first time, for the forty-fifth anniversary of Elvis Presley’s death. The name does not feel apt. Surrounded by sweaty, mutton-chopped worshippers in shiny polyester jumpsuits, women with wrinkly tattoos, and little boys in capes, I gulp down hot, syrupy banana glopped with peanut butter on smashed Bunny Bread to condition myself, then set out to meet the fans who keep a dead man alive as an engine of consumerism, a weird religion, and an inexplicable (to me) lifelong obsession. What if I told you the next energy revolution isn’t in the sky, but under your feet?

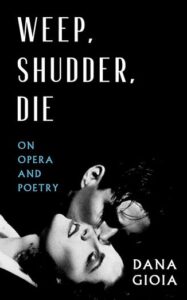

What if I told you the next energy revolution isn’t in the sky, but under your feet? Poet and former National Endowment for the Arts chairman

Poet and former National Endowment for the Arts chairman  In his new book,

In his new book,  NEAR THE END of Samantha Allen’s new novel Roland Rogers Isn’t Dead Yet, a memoirist who’s been moonlighting as a ghostwriter confides that he isn’t really an artist anymore, or anyway not the kind who’ll likely win a National Book Award. “I’m never going to be one of those waiflike, purple prose–writing authors who gets cover blurbs like ‘delicate and masterful’ or ‘a powerful meditation on X, Y, and Z.’”

NEAR THE END of Samantha Allen’s new novel Roland Rogers Isn’t Dead Yet, a memoirist who’s been moonlighting as a ghostwriter confides that he isn’t really an artist anymore, or anyway not the kind who’ll likely win a National Book Award. “I’m never going to be one of those waiflike, purple prose–writing authors who gets cover blurbs like ‘delicate and masterful’ or ‘a powerful meditation on X, Y, and Z.’” W

W LUMS is proud and thrilled to acquire the Lutfullah Khan Sound Archive, the premier repository for the literary, cultural, musical, and intellectual heritage of Pakistan and the wider region. There is no other audio library in the region that comes close to matching the scale, richness, and uniqueness of this incredible collection that is bound to serve as an invaluable resource for interdisciplinary scholarship, student learning, and community outreach across various disciplines, including history, sociology, religion, cultural studies, musicology, film studies, and more.

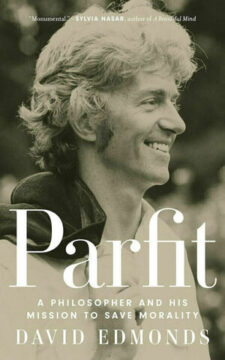

LUMS is proud and thrilled to acquire the Lutfullah Khan Sound Archive, the premier repository for the literary, cultural, musical, and intellectual heritage of Pakistan and the wider region. There is no other audio library in the region that comes close to matching the scale, richness, and uniqueness of this incredible collection that is bound to serve as an invaluable resource for interdisciplinary scholarship, student learning, and community outreach across various disciplines, including history, sociology, religion, cultural studies, musicology, film studies, and more. David Edmonds’ Parfit belongs to a burgeoning genre. There are the two recent collective biographies of Anscombe, Foot, Midgley and Murdoch (by Benjamin Lipscomb and by Claire Mac Cumhaill and Rachael Wiseman). There are M.W. Rowe’s J.L. Austin: Philosopher and D-Day Intelligence Officer and Nikhil Krishnan’s A Terribly Serious Adventure. Earlier works include Ray Monk’s Russell and Wittgenstein volumes, Tom Regan’s Bloomsbury’s Prophet, and Bart Schultz’s books on Sidgwick and the other classical utilitarians. And Edmonds himself is inter alia the author of The Murder of Professor Schlick and the coauthor of Wittgenstein’s Poker.

David Edmonds’ Parfit belongs to a burgeoning genre. There are the two recent collective biographies of Anscombe, Foot, Midgley and Murdoch (by Benjamin Lipscomb and by Claire Mac Cumhaill and Rachael Wiseman). There are M.W. Rowe’s J.L. Austin: Philosopher and D-Day Intelligence Officer and Nikhil Krishnan’s A Terribly Serious Adventure. Earlier works include Ray Monk’s Russell and Wittgenstein volumes, Tom Regan’s Bloomsbury’s Prophet, and Bart Schultz’s books on Sidgwick and the other classical utilitarians. And Edmonds himself is inter alia the author of The Murder of Professor Schlick and the coauthor of Wittgenstein’s Poker.