Dwight Garner at the New York Times:

At what point does an aside become a tangent, a tangent a digression, a digression a meander, a meander a ramble, a ramble a circumlocution, a circumlocution an excursus and an excursus a cul-de-sac? The reader has time to consider such matters while reading A.N. Wilson’s elastic-waisted but hardly unintelligent new biography, “Goethe: His Faustian Life.”

At what point does an aside become a tangent, a tangent a digression, a digression a meander, a meander a ramble, a ramble a circumlocution, a circumlocution an excursus and an excursus a cul-de-sac? The reader has time to consider such matters while reading A.N. Wilson’s elastic-waisted but hardly unintelligent new biography, “Goethe: His Faustian Life.”

Wilson is a prolific English biographer (of Darwin, Tolstoy, Milton and Queen Victoria, among others) and novelist whose books are usually worth attending to. Especially recommended is his bittersweet memoir “Confessions: A Life of Failed Promises,” from 2022. Two of his daughters, the classicist Emily Wilson and the food writer Bee Wilson, are inimitable writers as well. Does the world need another biography of the German polymath Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832), the author of the novels “The Sorrows of Young Werther” and “Elective Affinities” as well as “Faust,” his masterpiece, a tragic play in two parts?

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

One Hundred Years of Solitude has a near-mythical status for me that no other book does. Aged about 14, bored one day during the summer holidays, I found the Picador 1978 paperback edition on my parents’ bookshelf. I opened it on a whim, and read one of the most iconic first sentences in existence: “Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice.” I immediately sat down on the sofa and read for a further three hours. I date my life as a reader of literature to that afternoon, to that first sentence which I still know by heart. I have since reread it only once, 10 years later, because I wanted to wait until I had forgotten what happens. I’ll read it again as soon as the details have once more faded from my memory, and I can’t wait.

One Hundred Years of Solitude has a near-mythical status for me that no other book does. Aged about 14, bored one day during the summer holidays, I found the Picador 1978 paperback edition on my parents’ bookshelf. I opened it on a whim, and read one of the most iconic first sentences in existence: “Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice.” I immediately sat down on the sofa and read for a further three hours. I date my life as a reader of literature to that afternoon, to that first sentence which I still know by heart. I have since reread it only once, 10 years later, because I wanted to wait until I had forgotten what happens. I’ll read it again as soon as the details have once more faded from my memory, and I can’t wait. A

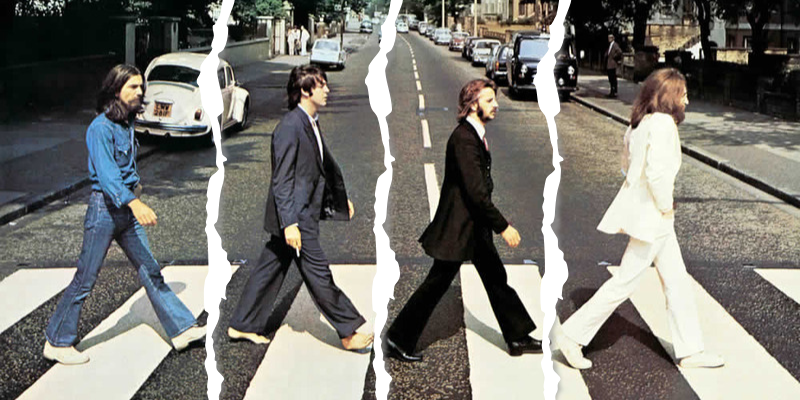

A “Looking back on it, we did used to say, it’s like a divorce,” Paul McCartney reflected on the Beatles’ breakup, now a marathon heading into its fifth year. “It really was like that, but four fellas trying to divorce instead of a man and a woman. And then you get four sets of lawyers instead of just two. All of that kind of stuff was not making life easy at all.” At the moment, the lawyers were not the problem.

“Looking back on it, we did used to say, it’s like a divorce,” Paul McCartney reflected on the Beatles’ breakup, now a marathon heading into its fifth year. “It really was like that, but four fellas trying to divorce instead of a man and a woman. And then you get four sets of lawyers instead of just two. All of that kind of stuff was not making life easy at all.” At the moment, the lawyers were not the problem. Artificial intelligence often gets criticized because it makes up information that appears to be factual, known as

Artificial intelligence often gets criticized because it makes up information that appears to be factual, known as  Written toward the end of Franz Kafka’s life, “Investigations of a Dog” is one of the lesser-known and most enigmatic works in the author’s oeuvre. Kafka didn’t give the story a title, writing it in the autumn of 1922 but leaving it unpublished and unfinished. It was published posthumously in 1931 in a collection edited by his friend and biographer Max Brod, who named it Forschungen eines Hundes — which could also be translated as “Researches of a Dog,” to give it a more academic ring.

Written toward the end of Franz Kafka’s life, “Investigations of a Dog” is one of the lesser-known and most enigmatic works in the author’s oeuvre. Kafka didn’t give the story a title, writing it in the autumn of 1922 but leaving it unpublished and unfinished. It was published posthumously in 1931 in a collection edited by his friend and biographer Max Brod, who named it Forschungen eines Hundes — which could also be translated as “Researches of a Dog,” to give it a more academic ring. This is an important book. It gathers the fruit of recent research on women in ancient philosophy, and across twelve chapters (all very well-written) offers the reader food for thought on a huge range of topics. We meet scientists and Cyrenaics, Epicurean sex workers and neo-Platonist mathematicians. Two chapters take us outside the standard story of Mediterranean antiquity, and we learn much from these perspective-shifting chapters. For example, Ban Zhao stands out as what, in the Greek tradition, we’d call a phronima: a woman who uses her practical wisdom to write philosophical texts even against the backdrop of difficult cultural headwinds that would seem to make a woman in philosophy an impossibility. While readers might be tempted to skip to the chapters that serve their current research interests, I would strongly encourage taking a look at the whole book: it is more than a sum of its parts, because the recurring themes look different precisely when they’re understood to be recurring.

This is an important book. It gathers the fruit of recent research on women in ancient philosophy, and across twelve chapters (all very well-written) offers the reader food for thought on a huge range of topics. We meet scientists and Cyrenaics, Epicurean sex workers and neo-Platonist mathematicians. Two chapters take us outside the standard story of Mediterranean antiquity, and we learn much from these perspective-shifting chapters. For example, Ban Zhao stands out as what, in the Greek tradition, we’d call a phronima: a woman who uses her practical wisdom to write philosophical texts even against the backdrop of difficult cultural headwinds that would seem to make a woman in philosophy an impossibility. While readers might be tempted to skip to the chapters that serve their current research interests, I would strongly encourage taking a look at the whole book: it is more than a sum of its parts, because the recurring themes look different precisely when they’re understood to be recurring. We tend to view the figure of the medieval and Renaissance fool or jester through 19th-century filters – to think of Victor Hugo’s Quasimodo and Verdi’s Rigoletto. Perhaps the show’s most striking achievement is to transcend these anachronistic and wistful habits and to reveal how much more complicated – and fascinating – the world of the fool has been.

We tend to view the figure of the medieval and Renaissance fool or jester through 19th-century filters – to think of Victor Hugo’s Quasimodo and Verdi’s Rigoletto. Perhaps the show’s most striking achievement is to transcend these anachronistic and wistful habits and to reveal how much more complicated – and fascinating – the world of the fool has been. The English historian J.A. Froude was famously gloomy about the ultimate prospects for his chosen branch of literature. “To be entirely just in our estimate of other ages is not difficult,” he said. “It is impossible.” Froude’s words came to mind the other day when I encountered Tucker Carlson’s interview with the podcaster Darryl Cooper, whose opinions about World War II may politely be described as “controversial.”

The English historian J.A. Froude was famously gloomy about the ultimate prospects for his chosen branch of literature. “To be entirely just in our estimate of other ages is not difficult,” he said. “It is impossible.” Froude’s words came to mind the other day when I encountered Tucker Carlson’s interview with the podcaster Darryl Cooper, whose opinions about World War II may politely be described as “controversial.” T

T I now present to you the Ultimate List, otherwise known as the List of Lists—in which I read all the Best Of lists and count which books are recommended most.

I now present to you the Ultimate List, otherwise known as the List of Lists—in which I read all the Best Of lists and count which books are recommended most. On December 20, OpenAI’s o3 system scored 85% on the

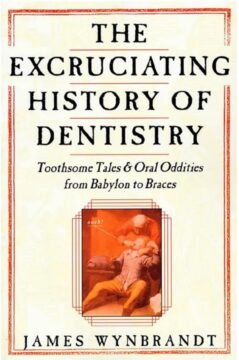

On December 20, OpenAI’s o3 system scored 85% on the  The writer P. J. O’Rourke famously quipped, “When you think of the good old days, think one word: dentistry.” So let us take his advice. James Wynbrandt’s The Excruciating History of Dentistry: Toothsome Tales & Oral Oddities from Babylon to Braces provides plenty to chew on. As the New York Times Book Review put it, “Wynbrandt has clearly done his homework.”

The writer P. J. O’Rourke famously quipped, “When you think of the good old days, think one word: dentistry.” So let us take his advice. James Wynbrandt’s The Excruciating History of Dentistry: Toothsome Tales & Oral Oddities from Babylon to Braces provides plenty to chew on. As the New York Times Book Review put it, “Wynbrandt has clearly done his homework.” Sharks present an interesting case study because unlike other fast swimmers such as tuna or swordfish, which have smooth skin surfaces, shark skin is rough—covered in teeth-like structures called denticles. Although ichthyologists have known for decades that denticles likely hold the key to a shark’s ability to quickly and efficiently move through the water, how they contribute to speed remained a mystery.

Sharks present an interesting case study because unlike other fast swimmers such as tuna or swordfish, which have smooth skin surfaces, shark skin is rough—covered in teeth-like structures called denticles. Although ichthyologists have known for decades that denticles likely hold the key to a shark’s ability to quickly and efficiently move through the water, how they contribute to speed remained a mystery. I

I When exactly did we stop

When exactly did we stop