Ari Schulman in The New Atlantis:

Shocking if not surprising investigations from the Wall Street Journal and ABC News find that pilots at Reagan National Airport, also known as DCA, had been formally warning the Federal Aviation Administration for more than three decades of nearly hitting military helicopters traversing the same corridor. Pilots who had faced this exact situation filed these reports to the FAA’s Aviation Safety Reporting System:

Shocking if not surprising investigations from the Wall Street Journal and ABC News find that pilots at Reagan National Airport, also known as DCA, had been formally warning the Federal Aviation Administration for more than three decades of nearly hitting military helicopters traversing the same corridor. Pilots who had faced this exact situation filed these reports to the FAA’s Aviation Safety Reporting System:

- In 2013: “I cannot imagine what business is so pressing that these helicopters are allowed to cross the path of airliners carrying hundreds of people! What would normally be alarming at any other airport in the country has become commonplace at DCA.”

- In 2006: “Why does the tower allow such nonsense by the military in such a critical area? This is a safety issue, and needs to be fixed.”

- In 1993: “This is an accident waiting to happen.”

- In 1991: “Here is an accident waiting to happen.”

An investigation by the Washington Post is even more damning. Using simple, publicly available information, the Post’s reporters quickly discovered what the FAA had missed or ignored: The helicopter flight path and the airplane landing path at their closest point have a vertical separation of just 15 feet.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Sexual partners transfer their distinctive genital microbiome to each other during intercourse, a finding that could have implications for forensic investigations of sexual assault.

Sexual partners transfer their distinctive genital microbiome to each other during intercourse, a finding that could have implications for forensic investigations of sexual assault. The year 2014 was a heady moment in the economic policy world. That spring, French economist Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century was published in English to astounding commercial and intellectual

The year 2014 was a heady moment in the economic policy world. That spring, French economist Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century was published in English to astounding commercial and intellectual

“The freedom to write”: PEN America’s

“The freedom to write”: PEN America’s  Questions concerning the differences between Schelling’s and Hegel’s philosophical systems have always been of intense interest. This has been the case since Hegel decisively ended their friendship and collaboration by critically describing the early Schelling’s concept of the Absolute (the identity of identity and non-identity, or A=A [Dews, 75–76]) as the night “in which all cows are black” in the Phenomenology of Spirit in 1807 (Hegel 1977, 9, cf. Dews 75). Schelling’s Absolute, on Hegel’s account, was an abyss of darkness within which the dynamic development of real difference did not emerge. In contrast, Hegel thought his own dialectical system could lift difference out of the night, capturing the “reality of the finite” and the dynamic process of becoming (77). While Schelling quickly moved on from the “Identity System” in question, Hegel nevertheless remained an inescapable shadow haunting Schelling’s philosophical career.

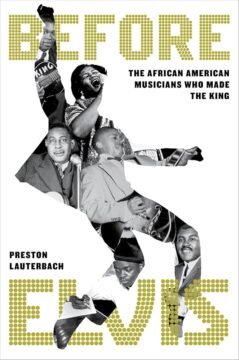

Questions concerning the differences between Schelling’s and Hegel’s philosophical systems have always been of intense interest. This has been the case since Hegel decisively ended their friendship and collaboration by critically describing the early Schelling’s concept of the Absolute (the identity of identity and non-identity, or A=A [Dews, 75–76]) as the night “in which all cows are black” in the Phenomenology of Spirit in 1807 (Hegel 1977, 9, cf. Dews 75). Schelling’s Absolute, on Hegel’s account, was an abyss of darkness within which the dynamic development of real difference did not emerge. In contrast, Hegel thought his own dialectical system could lift difference out of the night, capturing the “reality of the finite” and the dynamic process of becoming (77). While Schelling quickly moved on from the “Identity System” in question, Hegel nevertheless remained an inescapable shadow haunting Schelling’s philosophical career. The further we get from Elvis Presley’s death, the more a crude music industry frame takes hold: the blinding flash of his Sun Records youth, the snowballing Hollywood banality, and the celebrity pill junkie slumped on his toilet, dead at 42. Praise Allah for recent documentaries like Elvis Presley: The Searcher (Thom Zimny, 2018), and the Reinventing Elvis: The ’68 Comeback (John Scheinfeld, 2023), where the performer’s radical charisma speaks for itself. In the same way that historic recreations always comment on their contemporary context, the Elvis Presley of Sun Studios and early RCA singles between 1954 and 1958 will always sound tantalizingly out of reach to 21st-century ears—another 80 years of laissez-faire racism will do that.

The further we get from Elvis Presley’s death, the more a crude music industry frame takes hold: the blinding flash of his Sun Records youth, the snowballing Hollywood banality, and the celebrity pill junkie slumped on his toilet, dead at 42. Praise Allah for recent documentaries like Elvis Presley: The Searcher (Thom Zimny, 2018), and the Reinventing Elvis: The ’68 Comeback (John Scheinfeld, 2023), where the performer’s radical charisma speaks for itself. In the same way that historic recreations always comment on their contemporary context, the Elvis Presley of Sun Studios and early RCA singles between 1954 and 1958 will always sound tantalizingly out of reach to 21st-century ears—another 80 years of laissez-faire racism will do that. The advent of advanced AI systems capable of generating academic text — including “chain-of-thought” large language models with test-time web access — is poised to significantly influence scholarly writing and publishing. This review discusses how academia, particularly in quantitative social science, should adjust over the next decade to AI-assisted or AI-written articles. We summarize the current capabilities of AI in academic writing (from drafting and citation support to idea generation), highlight emerging trends, and weigh advantages against risks such as misinformation, plagiarism, and ethical dilemmas. We then offer speculative predictions for the coming ten years, grounded in literature and present data on AI’s impact to date. An empirical analysis compiles real-world data illustrating AI’s growing footprint in research output. Finally, we provide policy and workflow recommendations for journals, peer reviewers, editors, and scholars, presented in an exhaustive table. Our aim is to inform a balanced approach to harnessing AI’s benefits in academic writing while safeguarding integrity

The advent of advanced AI systems capable of generating academic text — including “chain-of-thought” large language models with test-time web access — is poised to significantly influence scholarly writing and publishing. This review discusses how academia, particularly in quantitative social science, should adjust over the next decade to AI-assisted or AI-written articles. We summarize the current capabilities of AI in academic writing (from drafting and citation support to idea generation), highlight emerging trends, and weigh advantages against risks such as misinformation, plagiarism, and ethical dilemmas. We then offer speculative predictions for the coming ten years, grounded in literature and present data on AI’s impact to date. An empirical analysis compiles real-world data illustrating AI’s growing footprint in research output. Finally, we provide policy and workflow recommendations for journals, peer reviewers, editors, and scholars, presented in an exhaustive table. Our aim is to inform a balanced approach to harnessing AI’s benefits in academic writing while safeguarding integrity Sometime in the 1980s, an unprecedented change in the human condition occurred. For the first time in known history, the average person on Earth had enough to eat all the time.

Sometime in the 1980s, an unprecedented change in the human condition occurred. For the first time in known history, the average person on Earth had enough to eat all the time.

Fischer and his colleagues focused on detecting enzymes called proteases, which break down proteins and are active in tumours, even from the very early stages. They specifically looked at the activity of matrix metalloproteinases involved in chewing up collagen and the extracellular matrix, which helps tumours to invade the body.

Fischer and his colleagues focused on detecting enzymes called proteases, which break down proteins and are active in tumours, even from the very early stages. They specifically looked at the activity of matrix metalloproteinases involved in chewing up collagen and the extracellular matrix, which helps tumours to invade the body.