Ezra Klein at the NYT:

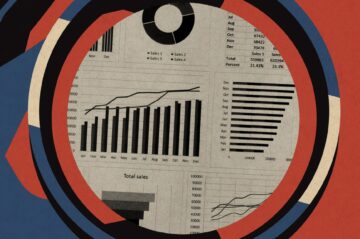

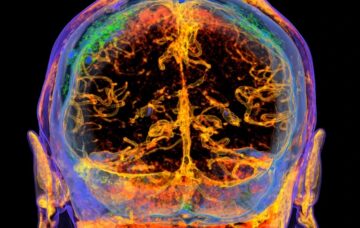

For the last couple of months, I have had this strange experience: Person after person — from artificial intelligence labs, from government — has been coming to me saying: It’s really about to happen. We’re about to get to artificial general intelligence.

For the last couple of months, I have had this strange experience: Person after person — from artificial intelligence labs, from government — has been coming to me saying: It’s really about to happen. We’re about to get to artificial general intelligence.

What they mean is that they have believed, for a long time, that we are on a path to creating transformational artificial intelligence capable of doing basically anything a human being could do behind a computer — but better. They thought it would take somewhere from five to 15 years to develop. But now they believe it’s coming in two to three years, during Donald Trump’s second term. They believe it because of the products they’re releasing right now and what they’re seeing inside the places they work. And I think they’re right.

If you’ve been telling yourself this isn’t coming, I really think you need to question that. It’s not web3. It’s not vaporware. A lot of what we’re talking about is already here, right now.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Michel de Montaigne is often upheld as a model of the examined life. In her introduction to What Do I Know? (the latest selection of Montaigne’s essays, translated by David Coward and published in 2023 by Pushkin Press), Yiyun Li writes: “For me, his writing serves as a reminder, a prompt, even, a mandate: a regular meditation on selfhood, like daily yoga, is a healthy habit.” And in M.A. Screech’s introduction to his translation of the Essays, he describes it as “one of Europe’s great bedside books.” Alain de Botton likewise included Montaigne in his book The Consolations of Philosophy as a helpful guide for thinking about the problem of self-esteem, and in his book The School of Life, he writes that the Essays “amounted to a practical compendium of advice on helping us to know our fickle minds, find purpose, connect meaningfully with others and achieve intervals of composure and acceptance.”

Michel de Montaigne is often upheld as a model of the examined life. In her introduction to What Do I Know? (the latest selection of Montaigne’s essays, translated by David Coward and published in 2023 by Pushkin Press), Yiyun Li writes: “For me, his writing serves as a reminder, a prompt, even, a mandate: a regular meditation on selfhood, like daily yoga, is a healthy habit.” And in M.A. Screech’s introduction to his translation of the Essays, he describes it as “one of Europe’s great bedside books.” Alain de Botton likewise included Montaigne in his book The Consolations of Philosophy as a helpful guide for thinking about the problem of self-esteem, and in his book The School of Life, he writes that the Essays “amounted to a practical compendium of advice on helping us to know our fickle minds, find purpose, connect meaningfully with others and achieve intervals of composure and acceptance.” Mother Nature is perhaps the most powerful generative “intelligence.” With just four genetic letters—A, T, C, and G—she has crafted the dazzling variety of life on Earth.

Mother Nature is perhaps the most powerful generative “intelligence.” With just four genetic letters—A, T, C, and G—she has crafted the dazzling variety of life on Earth. Tom Wolfe’s books are being

Tom Wolfe’s books are being

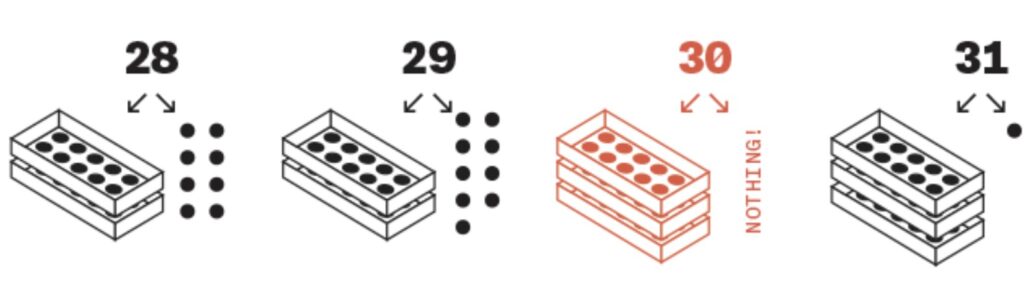

The publication process in social science is broken. Articles in prestigious journals use flawed data, employ questionable research practices, and reach illogical conclusions. Sometimes doubts over research become public, such as in the

The publication process in social science is broken. Articles in prestigious journals use flawed data, employ questionable research practices, and reach illogical conclusions. Sometimes doubts over research become public, such as in the  DON DIEGO DE ZAMA works as a counselor for the provincial Gobernador, but what this post entails is difficult to discern, because he takes great pains to do anything and everything but his job. Instead of performing his duties, he seethes, nurses grudges, squanders his money, erupts into paroxysms of rage, and lusts after women he does not succeed in courting. Occasionally, he performs the odd bureaucratic task or half-heartedly meets with a petitioner, but his true vocation is resentment. He is an Americano—a white man and an officer of the Spanish crown who was born in Latin America, for which reason he cannot aspire to the promotions or privileges afforded his Spanish-born colleagues. At most, he can hope for a transfer to a more central Latin American city and a reunion with his wife and sons, who remain in a distant part of the viceroyalty. In the meantime, he victimizes his mixed-race and Indigenous subordinates, loses his temper, and waits. “My career was stagnating in a post that was, it had been implied from the start, only a stopgap appointment,” he groans. In the first scene of the book, he spots a monkey corpse floating in the water by the docks without drifting further down the river and immediately identifies himself with it: “There we were: ready to go and not going.”

DON DIEGO DE ZAMA works as a counselor for the provincial Gobernador, but what this post entails is difficult to discern, because he takes great pains to do anything and everything but his job. Instead of performing his duties, he seethes, nurses grudges, squanders his money, erupts into paroxysms of rage, and lusts after women he does not succeed in courting. Occasionally, he performs the odd bureaucratic task or half-heartedly meets with a petitioner, but his true vocation is resentment. He is an Americano—a white man and an officer of the Spanish crown who was born in Latin America, for which reason he cannot aspire to the promotions or privileges afforded his Spanish-born colleagues. At most, he can hope for a transfer to a more central Latin American city and a reunion with his wife and sons, who remain in a distant part of the viceroyalty. In the meantime, he victimizes his mixed-race and Indigenous subordinates, loses his temper, and waits. “My career was stagnating in a post that was, it had been implied from the start, only a stopgap appointment,” he groans. In the first scene of the book, he spots a monkey corpse floating in the water by the docks without drifting further down the river and immediately identifies himself with it: “There we were: ready to go and not going.” I

I THE YEAR IS 2008. David Foster Wallace has just died by suicide and every Spanish-language writer is rushing to their blog to post a heartfelt obituary for their favorite North American novelist.

THE YEAR IS 2008. David Foster Wallace has just died by suicide and every Spanish-language writer is rushing to their blog to post a heartfelt obituary for their favorite North American novelist.  A slimy barrier lining

A slimy barrier lining  F

F Democrats, let the Republicans’ own undertow drag them away. At this rate, the Trump honeymoon will be over, best case, by Memorial Day but more likely in the next 30 days. And in November 2025, we start turning the tide with what will be remembered as one of the most important elections in recent years: the Virginia governor’s race. From tax enforcers to rocket scientists, bank regulators and essential workers — the Trump administration is hellbent on

Democrats, let the Republicans’ own undertow drag them away. At this rate, the Trump honeymoon will be over, best case, by Memorial Day but more likely in the next 30 days. And in November 2025, we start turning the tide with what will be remembered as one of the most important elections in recent years: the Virginia governor’s race. From tax enforcers to rocket scientists, bank regulators and essential workers — the Trump administration is hellbent on