Michelle Peng in Time Magazine:

Engagement scores for US workers fell to a 10-year low in January, a dip that coincides with workers’ falling confidence that someone at work cares about them as a person or supports their development at work, according to Gallup. For Karyn Twaronite, global vice chair of diversity, equity, and inclusiveness at EY, this rising level of isolation and loneliness is fundamentally an inclusion issue.

Engagement scores for US workers fell to a 10-year low in January, a dip that coincides with workers’ falling confidence that someone at work cares about them as a person or supports their development at work, according to Gallup. For Karyn Twaronite, global vice chair of diversity, equity, and inclusiveness at EY, this rising level of isolation and loneliness is fundamentally an inclusion issue.

“My job is to make sure that more of our people feel more included all the time,” she says, pointing out that the work also has a clear business case: “The lonelier people are at work, the less committed and less engaged they are.” Increase belonging and inclusion, on the other hand, and employers can also see productivity, engagement, and commitment rise.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Some of the microbes that rose from the ocean fell on land instead of water. Lying on the bare continents, they no longer had sea water to shield them from direct sunlight. Many likely died as the ultraviolet radiation ravaged their genes and proteins. Meanwhile, the atmosphere was sucking out the water from their interiors, causing their molecules to stick together and collapse into toxic shapes.

Some of the microbes that rose from the ocean fell on land instead of water. Lying on the bare continents, they no longer had sea water to shield them from direct sunlight. Many likely died as the ultraviolet radiation ravaged their genes and proteins. Meanwhile, the atmosphere was sucking out the water from their interiors, causing their molecules to stick together and collapse into toxic shapes.

In his introduction, Clark poses a more immediate question: “Shouldn’t we judge political art by its effects, not its beauty or truth?” Leaving aside the second clause, we find two questionable assertions implicit in the first: namely, that art can be political and that it can have an effect. In this context, he imagines the reader wondering why his book “makes room for Matisse and Jackson Pollock,” two artists who “reached the conclusion, in practice, that opinions had to be what art annihilated if it was to survive”. Their stance is one that Clark accepts: “The blankness was essential. It was reality as they lived it.”

In his introduction, Clark poses a more immediate question: “Shouldn’t we judge political art by its effects, not its beauty or truth?” Leaving aside the second clause, we find two questionable assertions implicit in the first: namely, that art can be political and that it can have an effect. In this context, he imagines the reader wondering why his book “makes room for Matisse and Jackson Pollock,” two artists who “reached the conclusion, in practice, that opinions had to be what art annihilated if it was to survive”. Their stance is one that Clark accepts: “The blankness was essential. It was reality as they lived it.”

For those hoping to cure death, and they are legion, a 2016 experiment at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in San Diego has become liminal — the moment that changed everything. The experiment involved mice born to live fast and die young, bred with a rodent version of progeria, a condition that causes premature aging. Left alone, the animals grow gray and frail and then die about seven months later, compared to a lifespan of about two years for typical lab mice.

For those hoping to cure death, and they are legion, a 2016 experiment at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in San Diego has become liminal — the moment that changed everything. The experiment involved mice born to live fast and die young, bred with a rodent version of progeria, a condition that causes premature aging. Left alone, the animals grow gray and frail and then die about seven months later, compared to a lifespan of about two years for typical lab mice. The Great Gatsby

The Great Gatsby It’s no secret that modern English is saturated with French. Insults and derogatory terms owe much to the French example – bastard, brute, coward, rascal, idiot. French oozes from the language of food and drink: chowder echoes the old French chaudière, meaning a cooking pot, while crayfish started out as escrevise before the English chopped off its initial vowel (something they also did with scarf, stew, slice and a host of others) and decided that the last syllable sounding like ‘fish’ was just too good to pass up. From arson to evidence, jury to slander, French runs through the language of the English law (and the ‘Oyez! Oyez! Oyez!’ of the

It’s no secret that modern English is saturated with French. Insults and derogatory terms owe much to the French example – bastard, brute, coward, rascal, idiot. French oozes from the language of food and drink: chowder echoes the old French chaudière, meaning a cooking pot, while crayfish started out as escrevise before the English chopped off its initial vowel (something they also did with scarf, stew, slice and a host of others) and decided that the last syllable sounding like ‘fish’ was just too good to pass up. From arson to evidence, jury to slander, French runs through the language of the English law (and the ‘Oyez! Oyez! Oyez!’ of the  I avoid contact with fans. Occasionally, I watch trash TV because I think the poet shouldn’t avert his eyes. I want to know what others aspire to. I’m a good but limited cook. My steaks are excellent, but they’ll never touch what you can get on any street corner in Argentina. Tree huggers are suspicious to me. Yoga classes for five-year-olds—which in California are a thing—are suspicious to me. I don’t use social media. If you see my profile anywhere there, you can be sure it’s a fake. I don’t use a smartphone. I never quite trust the media, so I get a truer picture of the political situation by going to multiple sources—the Western media, Al Jazeera, Russian TV, and occasionally by downloading the whole of a politician’s speech. I trust the Oxford English Dictionary, which is one of mankind’s greatest cultural achievements. I mean the one in twenty massive volumes with six hundred thousand entries and more than three million quotations culled from all over the English-speaking world and over a thousand years. I reckon thousands of researchers and amateur helpers spent 150 years combing through everything recorded. For me, it is the book of books, the one I would take to a desert island. It is inexhaustible, a miracle. The first time I visited Oliver Sacks on Wards Island north of Manhattan, I had mislaid the house number but knew the name of the little street. It was evening, winter-time; the slightly sloping street was icy. I parked and tiptoed along the icy pavement looking into every lit-up home. None of the windows had curtains. Through one window I saw a man sprawled on a sofa with one of the hefty volumes of the OED propped on his chest. I knew that had to be him, and so it was. Our first subject was the dictionary; for him as well, it was the book of books.

I avoid contact with fans. Occasionally, I watch trash TV because I think the poet shouldn’t avert his eyes. I want to know what others aspire to. I’m a good but limited cook. My steaks are excellent, but they’ll never touch what you can get on any street corner in Argentina. Tree huggers are suspicious to me. Yoga classes for five-year-olds—which in California are a thing—are suspicious to me. I don’t use social media. If you see my profile anywhere there, you can be sure it’s a fake. I don’t use a smartphone. I never quite trust the media, so I get a truer picture of the political situation by going to multiple sources—the Western media, Al Jazeera, Russian TV, and occasionally by downloading the whole of a politician’s speech. I trust the Oxford English Dictionary, which is one of mankind’s greatest cultural achievements. I mean the one in twenty massive volumes with six hundred thousand entries and more than three million quotations culled from all over the English-speaking world and over a thousand years. I reckon thousands of researchers and amateur helpers spent 150 years combing through everything recorded. For me, it is the book of books, the one I would take to a desert island. It is inexhaustible, a miracle. The first time I visited Oliver Sacks on Wards Island north of Manhattan, I had mislaid the house number but knew the name of the little street. It was evening, winter-time; the slightly sloping street was icy. I parked and tiptoed along the icy pavement looking into every lit-up home. None of the windows had curtains. Through one window I saw a man sprawled on a sofa with one of the hefty volumes of the OED propped on his chest. I knew that had to be him, and so it was. Our first subject was the dictionary; for him as well, it was the book of books. On Saturday Francis Collins resigned from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) after directing it for over a decade. His departure, coming on the heels of the expected confirmation of Stanford’s Jay Bhattacharya as his replacement, represents more than the loss of an influential physician-scientist who once

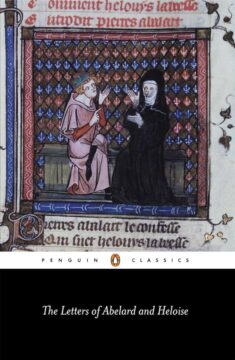

On Saturday Francis Collins resigned from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) after directing it for over a decade. His departure, coming on the heels of the expected confirmation of Stanford’s Jay Bhattacharya as his replacement, represents more than the loss of an influential physician-scientist who once  Whenever I read The Letters of Abelard and Héloïse I have in mind another, more contemporary couple, whose collaborative work I have come to think of as sacred, too. As soon as the performance artists Marina Abramović and Ulay met in the 1970s, they fell hard in love and began making performance art together. They called this work a “third energy,” their souls combined, a kind of artistic procreation (we don’t know what happened to Héloïse and Abelard’s child—only that she called him Astrolabe, after the astronomical instrument for reckoning with time and observing the stars. Astrolabe as the one instrument that could point up to the star-crossed lovers who made him and prove that their love had been real). The idea for “The Lovers” came to Abramović as a vision in a dream. They would walk from either end of the Great Wall of China to finally meet in the middle where they would marry, documenting the whole expedition on film—the kind of exaggeratedly cinematic, romantic scheme that is destined to go wrong. In the time it took to secure their visas—several years—the relationship had already begun to fall apart. Five years later, they set out at last to make “The Lovers.” After almost 90 days of walking, each covering over two thousand kilometres alone, they reunited on the wall, not to marry, but to break up. Watching the footage of “The Lovers,” I imagine they are actually Héloïse and Abelard, setting out on their private pilgrimages through life in the wake of their painful estrangement, then meeting in the middle again through the form of letters.

Whenever I read The Letters of Abelard and Héloïse I have in mind another, more contemporary couple, whose collaborative work I have come to think of as sacred, too. As soon as the performance artists Marina Abramović and Ulay met in the 1970s, they fell hard in love and began making performance art together. They called this work a “third energy,” their souls combined, a kind of artistic procreation (we don’t know what happened to Héloïse and Abelard’s child—only that she called him Astrolabe, after the astronomical instrument for reckoning with time and observing the stars. Astrolabe as the one instrument that could point up to the star-crossed lovers who made him and prove that their love had been real). The idea for “The Lovers” came to Abramović as a vision in a dream. They would walk from either end of the Great Wall of China to finally meet in the middle where they would marry, documenting the whole expedition on film—the kind of exaggeratedly cinematic, romantic scheme that is destined to go wrong. In the time it took to secure their visas—several years—the relationship had already begun to fall apart. Five years later, they set out at last to make “The Lovers.” After almost 90 days of walking, each covering over two thousand kilometres alone, they reunited on the wall, not to marry, but to break up. Watching the footage of “The Lovers,” I imagine they are actually Héloïse and Abelard, setting out on their private pilgrimages through life in the wake of their painful estrangement, then meeting in the middle again through the form of letters. To understand Trump’s political order, then, we need to familiarize ourselves with the

To understand Trump’s political order, then, we need to familiarize ourselves with the M

M