Elise Soutar at Paste:

For all the flowery adjectives and hyperbolic statements I’ve peddled through my writing over the past three years, I think that spur-of-the-moment assessment might be the most accurate statement about music I’ve ever verbalized. You could very well make the argument—as I suppose I am now—that the entire history of popular music (specifically in the U.K.) can be told through the life and career of Marianne Faithfull. There is a version of that history which I had been sold as a young person, just hungry to learn as much as I could. Yet, my reading and life experience over time have created a slow process of realizing I barely exist in that history—that the so-called “progressive” history of New Hollywood and the rock era mainly spelt freedom for those who already had it. I would never deny the importance or quality of so much of that work, but double-standards present themselves the second you start scratching away at the carefully-maintained patina of “rock history.”

For all the flowery adjectives and hyperbolic statements I’ve peddled through my writing over the past three years, I think that spur-of-the-moment assessment might be the most accurate statement about music I’ve ever verbalized. You could very well make the argument—as I suppose I am now—that the entire history of popular music (specifically in the U.K.) can be told through the life and career of Marianne Faithfull. There is a version of that history which I had been sold as a young person, just hungry to learn as much as I could. Yet, my reading and life experience over time have created a slow process of realizing I barely exist in that history—that the so-called “progressive” history of New Hollywood and the rock era mainly spelt freedom for those who already had it. I would never deny the importance or quality of so much of that work, but double-standards present themselves the second you start scratching away at the carefully-maintained patina of “rock history.”

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

T

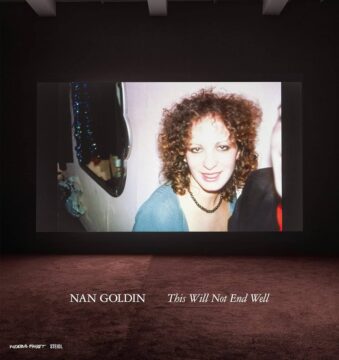

T Goldin’s sharp eye makes her stories simple, but it doesn’t make them easy. Sisters, Saints and Sibyls (2004-22) is a tribute to her elder sister, Barbara, who was institutionalised when she hit puberty and killed herself aged eighteen. A few years later, Nancy – as she was then – ran away from home. She was fostered and in 1968 landed in a ‘hippy free school’ called Satya, in Massachusetts. She spent as much time as she could at the Brattle Theatre and the Orson Welles cinema in Cambridge. The school had a grant from Polaroid, which was based nearby, and Goldin was one of the students given a camera. ‘Photography,’ she said recently, ‘was a way to walk through fear.’ As a teenager she was reticent and barely spoke, but became friends with a fellow student (and fellow photographer), David Armstrong. The camera became a solution to the problems of childhood, of growing up, of what was happening to her now – a way of proving her experiences were real.

Goldin’s sharp eye makes her stories simple, but it doesn’t make them easy. Sisters, Saints and Sibyls (2004-22) is a tribute to her elder sister, Barbara, who was institutionalised when she hit puberty and killed herself aged eighteen. A few years later, Nancy – as she was then – ran away from home. She was fostered and in 1968 landed in a ‘hippy free school’ called Satya, in Massachusetts. She spent as much time as she could at the Brattle Theatre and the Orson Welles cinema in Cambridge. The school had a grant from Polaroid, which was based nearby, and Goldin was one of the students given a camera. ‘Photography,’ she said recently, ‘was a way to walk through fear.’ As a teenager she was reticent and barely spoke, but became friends with a fellow student (and fellow photographer), David Armstrong. The camera became a solution to the problems of childhood, of growing up, of what was happening to her now – a way of proving her experiences were real. High in the skies of Earth, a new space race is underway. Here, just above the boundary where space begins, companies are trying to create a new class of daring satellites. Not quite high-altitude planes and not quite low-orbiting satellites, these sky skimmers are designed to race around our planet in an untapped region, with potentially huge benefits on offer.

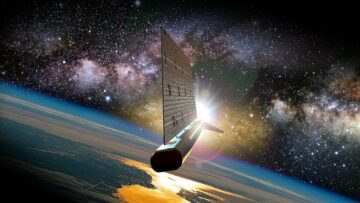

High in the skies of Earth, a new space race is underway. Here, just above the boundary where space begins, companies are trying to create a new class of daring satellites. Not quite high-altitude planes and not quite low-orbiting satellites, these sky skimmers are designed to race around our planet in an untapped region, with potentially huge benefits on offer. Google’s parent company lifting a longstanding ban on artificial intelligence (AI) being used for developing weapons and surveillance tools is “incredibly concerning”, a leading human rights group has said.

Google’s parent company lifting a longstanding ban on artificial intelligence (AI) being used for developing weapons and surveillance tools is “incredibly concerning”, a leading human rights group has said. For Kristian Cook, every pizza box he opened was another door closed on the path to overcoming obesity. “I had massive cravings for pizza,” he says. “That was my biggest downfall.” At 114 kilograms and juggling a daily regimen of medications for high cholesterol, hypertension and gout, the New Zealander resolved to take action. In late 2022, at the age of 46, Cook joined a clinical trial that set out to test a combination of the

For Kristian Cook, every pizza box he opened was another door closed on the path to overcoming obesity. “I had massive cravings for pizza,” he says. “That was my biggest downfall.” At 114 kilograms and juggling a daily regimen of medications for high cholesterol, hypertension and gout, the New Zealander resolved to take action. In late 2022, at the age of 46, Cook joined a clinical trial that set out to test a combination of the  Women have always had a special relationship with lies; often, we have relied on them for survival. But it was the aspirational feminism of the 2010s—individualistic, empowering, breathless, especially after SoulCycle—which first introduced many of us to the art of lying to ourselves.

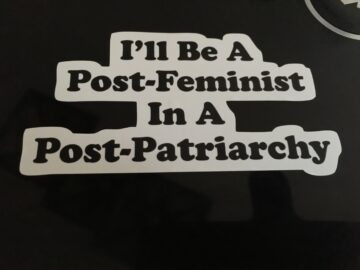

Women have always had a special relationship with lies; often, we have relied on them for survival. But it was the aspirational feminism of the 2010s—individualistic, empowering, breathless, especially after SoulCycle—which first introduced many of us to the art of lying to ourselves. QUIETLY, ALMOST ELUSIVELY, video has become the dominant medium of human communication. There are hundreds of billions of cameras out in the world filming as you’re reading this article. Two-thirds of global internet traffic is video; that number continues to climb. If we date print back to 1455 and

QUIETLY, ALMOST ELUSIVELY, video has become the dominant medium of human communication. There are hundreds of billions of cameras out in the world filming as you’re reading this article. Two-thirds of global internet traffic is video; that number continues to climb. If we date print back to 1455 and  In a column for The Point magazine, Agnes Callard, a philosopher and professor at the University of Chicago, comes out against advice. She makes her case using an anecdote involving the novelist Margaret Atwood. Asked about her advice for a group of aspiring writers, Atwood is stumped and ends up offering little more than bromides encouraging them to write every day and try not to be inhibited. Callard excuses Atwood’s banality, blaming it on the fundamental incoherence of the thing she was asked to produce.

In a column for The Point magazine, Agnes Callard, a philosopher and professor at the University of Chicago, comes out against advice. She makes her case using an anecdote involving the novelist Margaret Atwood. Asked about her advice for a group of aspiring writers, Atwood is stumped and ends up offering little more than bromides encouraging them to write every day and try not to be inhibited. Callard excuses Atwood’s banality, blaming it on the fundamental incoherence of the thing she was asked to produce.

We were fortunate that during our tenures in office no effort was made to unlawfully undermine the nation’s financial commitments. Regrettably,

We were fortunate that during our tenures in office no effort was made to unlawfully undermine the nation’s financial commitments. Regrettably,  Black History Month is a time to reflect on the central role of Black people in shaping this nation. Nowhere is that more evident than the labor movement. A founding tenet of American capitalism and our economy is that Black bodies are worth more than Black minds. This belief is continually demonstrated by the value placed on Black workers and their work. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Black workers risked their lives in essential jobs to keep the country operating. And in doing so faced an

Black History Month is a time to reflect on the central role of Black people in shaping this nation. Nowhere is that more evident than the labor movement. A founding tenet of American capitalism and our economy is that Black bodies are worth more than Black minds. This belief is continually demonstrated by the value placed on Black workers and their work. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Black workers risked their lives in essential jobs to keep the country operating. And in doing so faced an