Sally Adee in Noema:

We seem to be entering a new era of cries du coeur to gather more life, including plants, under the umbrella of intelligence. Bookstores these days are heaving with volumes with titles like “The Revolutionary Genius of Plants,” “Planta Sapiens” and “The Light Eaters.”

Their authors are not even at the vanguard anymore. Some boldly go even further, finding behavior they label intelligent in fungi, bacteria, slime molds and paramecia. Even the cells that constitute our bodies are now standing at the velvet ropes, backed by frontier scientists waving evidence of behavior that might qualify as the hallmarks of intelligence if it were observed in an animal.

What on Earth is going on? Should we consider everything to be intelligent now?

There’s some evidence that the question is exactly backward. A small but growing number of philosophers, physicists and developmental biologists say that, instead of continually admitting new creatures into the category of intelligence, the new findings are evidence that there is something catastrophically wrong with the way we understand intelligence itself. And they believe that if we can bring ourselves to dramatically reconsider what we think we know about it, we will end up with a much better concept of how to restabilize the balance between human and nonhuman life amid an ecological omnicrisis that threatens to permanently alter the trajectory of every living thing on Earth.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The jewelry designer Lola Oladunjoye remembers that she was sketching in the studio of her Paris apartment one day in late May 2020. She looked up at the television and, on CNN, watched in horror a video of George Floyd being fatally restrained

The jewelry designer Lola Oladunjoye remembers that she was sketching in the studio of her Paris apartment one day in late May 2020. She looked up at the television and, on CNN, watched in horror a video of George Floyd being fatally restrained  R

R To keep my vocabulary from shrinking, I signed up for one of those

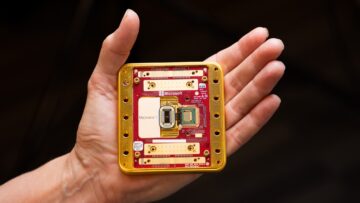

To keep my vocabulary from shrinking, I signed up for one of those  Researchers and companies have been working for years to build quantum computers, which

Researchers and companies have been working for years to build quantum computers, which  T

T P

P

Rap is original poetry recited in rhythm and rhyme over prerecorded instrumental tracks. Rap music (also referred to as rap or hip-hop music) evolved in conjunction with the cultural movement called hip-hop. Rap emerged as a minimalist street sound against the backdrop of the heavily orchestrated and formulaic music coming from the local house parties to dance clubs in the early 1970s. Its earliest performers comprise MCs (derived from master of ceremonies but referring to the actual rapper) and DJs (who use and often manipulate pre-recorded tracks as a backdrop to the rap), break dancers and graffiti writers.

Rap is original poetry recited in rhythm and rhyme over prerecorded instrumental tracks. Rap music (also referred to as rap or hip-hop music) evolved in conjunction with the cultural movement called hip-hop. Rap emerged as a minimalist street sound against the backdrop of the heavily orchestrated and formulaic music coming from the local house parties to dance clubs in the early 1970s. Its earliest performers comprise MCs (derived from master of ceremonies but referring to the actual rapper) and DJs (who use and often manipulate pre-recorded tracks as a backdrop to the rap), break dancers and graffiti writers.

Political outcomes would be relatively simple to predict and understand if only people were well-informed, entirely rational, and perfectly self-interested. Alas, real human beings are messy, emotional, imperfect creatures, so a successful theory of politics has to account for these features. One phenomenon that has grown in recent years is an alignment of cultural differences with political ones, so that polarization becomes more entrenched and even violent. I talk with political scientist Lilliana Mason about how this has come to pass, and how democracy can deal with it.

Political outcomes would be relatively simple to predict and understand if only people were well-informed, entirely rational, and perfectly self-interested. Alas, real human beings are messy, emotional, imperfect creatures, so a successful theory of politics has to account for these features. One phenomenon that has grown in recent years is an alignment of cultural differences with political ones, so that polarization becomes more entrenched and even violent. I talk with political scientist Lilliana Mason about how this has come to pass, and how democracy can deal with it. Monterroso has often been compared to Borges, and the comparisons are generally pretty apt. Both writers preoccupied themselves, formally, with short stories and essays that seem to merge into one another; both had a playful interest in scholarly arcana; both were obsessed with the question of style; and both were fascinated by parables and fables. But compared with the ironclad intertextuality of a writer like Borges, Monterroso’s own brand of self-referentiality isn’t exactly philosophically sound—a result, probably, of his antic disposition. It doesn’t approach, or even attempt to approach, the ideal of a closed system. Read a Borges story, and you often get a sense of the author going solemnly about his work like a monk. In a Monterroso story, the image called to mind is rather that of a clerk—one who is lazy, or bad at his job, or poorly trained, or some combination of the three. Things seem simply to have been misfiled.

Monterroso has often been compared to Borges, and the comparisons are generally pretty apt. Both writers preoccupied themselves, formally, with short stories and essays that seem to merge into one another; both had a playful interest in scholarly arcana; both were obsessed with the question of style; and both were fascinated by parables and fables. But compared with the ironclad intertextuality of a writer like Borges, Monterroso’s own brand of self-referentiality isn’t exactly philosophically sound—a result, probably, of his antic disposition. It doesn’t approach, or even attempt to approach, the ideal of a closed system. Read a Borges story, and you often get a sense of the author going solemnly about his work like a monk. In a Monterroso story, the image called to mind is rather that of a clerk—one who is lazy, or bad at his job, or poorly trained, or some combination of the three. Things seem simply to have been misfiled. Christopher Nolan’s film The Prestige presents a three-act structure said to apply to all great magic tricks. First is the pledge: the magician presents something ordinary, though the audience suspects that it isn’t. Next is the turn: the magician makes this ordinary object do something extraordinary, like disappear. Finally, there’s the prestige: the truly astounding moment, as when the object reappears in an unexpected way.

Christopher Nolan’s film The Prestige presents a three-act structure said to apply to all great magic tricks. First is the pledge: the magician presents something ordinary, though the audience suspects that it isn’t. Next is the turn: the magician makes this ordinary object do something extraordinary, like disappear. Finally, there’s the prestige: the truly astounding moment, as when the object reappears in an unexpected way.