Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Category: Recommended Reading

Lady Gaga’s New Album

Rich Juzwiak at Pitchfork:

Talk about truth in advertising: MAYHEM is its own charm offensive, a massive attack of good vibes. It is a project designed to remind listeners why they fell in love with her in the first place, before the jazz belting or the traditional singer-songwriter gravitas or movie stardom. Inspiration from fiancé Michael Polansky, entrepreneur and one of the album’s executive producers, to return to her pop roots prompted an internal survey—Gaga told EW that instead of seeking to reinvent her sound, “I started to think about what makes me me? What are my references? What are my inspirations?” MAYHEM, then, isn’t the sound of someone reheating her nachos on the sly and trying to pass them off as fresh—it’s a full-on cooking show devoted to the art of nacho-reheating.

Talk about truth in advertising: MAYHEM is its own charm offensive, a massive attack of good vibes. It is a project designed to remind listeners why they fell in love with her in the first place, before the jazz belting or the traditional singer-songwriter gravitas or movie stardom. Inspiration from fiancé Michael Polansky, entrepreneur and one of the album’s executive producers, to return to her pop roots prompted an internal survey—Gaga told EW that instead of seeking to reinvent her sound, “I started to think about what makes me me? What are my references? What are my inspirations?” MAYHEM, then, isn’t the sound of someone reheating her nachos on the sly and trying to pass them off as fresh—it’s a full-on cooking show devoted to the art of nacho-reheating.

If it sounds strange to say that it’s good to have Gaga back, it’s probably because she’s never really stayed away for too long. Between her proper sixth album, 2020’s Chromatica, and MAYHEM, Gaga played her Vegas residency and toured the world; was the best thing in two bad movies, 2021’s House of Gucci and 2024’s Joker: Folie à Deux; and released a companion album for the latter, the covers-heavy Harlequin.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Can We Solve the Parkinson’s Puzzle?

Paul Hond in Columbia Magazine:

Ping-pong is not a game that lends itself well to chatter. It demands sharp focus, quick reflexes, and a light touch, and the dozen players who have gathered this Monday afternoon at PingPod, a table-tennis venue on West 99th Street, are locked in the wordless rhythms of the back-and-forth. Aside from the occasional “Nice spin!” or grunt of self-reproach, the room is filled with the hollow percussion of little white balls glancing off paddles, skipping over the tops of the black tables, and rattling across the floor.

Ping-pong is not a game that lends itself well to chatter. It demands sharp focus, quick reflexes, and a light touch, and the dozen players who have gathered this Monday afternoon at PingPod, a table-tennis venue on West 99th Street, are locked in the wordless rhythms of the back-and-forth. Aside from the occasional “Nice spin!” or grunt of self-reproach, the room is filled with the hollow percussion of little white balls glancing off paddles, skipping over the tops of the black tables, and rattling across the floor.

Between games, one of the players, Lucy Miller ’81GS, praises the virtues of the activity. “Ping-pong is good for eye–hand coordination and coordination of the feet, so it’s good for people with Parkinson’s disease, because we have difficulty with those things,” Miller says. Like the other players here, Miller, who is seventy, is part of the New York chapter of a global organization called PingPongParkinson. Its members, all of whom have the disease, meet weekdays at ping-pong spots around Manhattan for community, exercise, and enjoyment. “It’s fun,” says Miller. “We have some pretty good players.”

Parkinson’s, or PD, is a progressive disorder in which brain cells involved in movement and coordination deteriorate and die.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

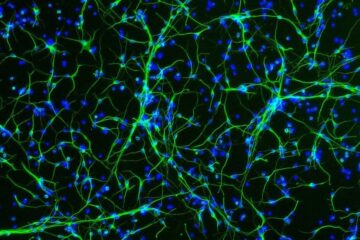

Aging Women’s Brain Mysteries Are Tested in Trio of Studies

Gina Kolata in The New York Times:

Women’s brains are superior to men’s in at least in one respect — they age more slowly. And now, a group of researchers reports that they have found a gene in mice that rejuvenates female brains. Humans have the same gene. The discovery suggests a possible way to help both women and men avoid cognitive declines in advanced age. The study was published Wednesday in the journal Science Advances. The journal also published two other studies on women’s brains, one on the effect of hormone therapy on the brain and another on how age at the onset of menopause shapes the risk of getting Alzheimer’s disease.

Women’s brains are superior to men’s in at least in one respect — they age more slowly. And now, a group of researchers reports that they have found a gene in mice that rejuvenates female brains. Humans have the same gene. The discovery suggests a possible way to help both women and men avoid cognitive declines in advanced age. The study was published Wednesday in the journal Science Advances. The journal also published two other studies on women’s brains, one on the effect of hormone therapy on the brain and another on how age at the onset of menopause shapes the risk of getting Alzheimer’s disease.

The evidence that women’s brains age more slowly than men’s seemed compelling. Researchers, looking at the way the brain uses blood sugar, had already found that the brains of aging women are years younger, in metabolic terms, than the brains of aging men.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

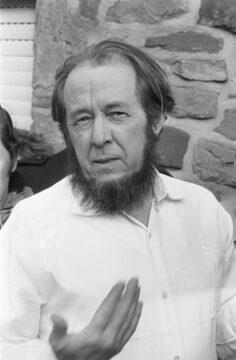

The Depletion Of Culture

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn at The New Criterion:

How irreversible, how irreparable is this process of mass vulgarization? Judging by the sphere of literature (the sphere closest to me), the path toward a reestablishment of high quality is not yet closed off, not yet taken from us, even if it will require a significant concentration of abilities and efforts. In principle, and according to the very nature of art—according to its flexibility and multifacetedness—the elite and the popular can coexist in a single work of literature: in successful cases, indeed, that work may be multileveled, written in such a way that it is accessible and satisfactory concurrently for readers of diverse levels of understanding and perception; and if a person experiences an elevation of level over time, he reads the same book with a newer understanding. Failure in achieving this is hardly preordained; but the author has to rise above the day-to-day demands of the publishing market, above calculations of assured near-term success.

How irreversible, how irreparable is this process of mass vulgarization? Judging by the sphere of literature (the sphere closest to me), the path toward a reestablishment of high quality is not yet closed off, not yet taken from us, even if it will require a significant concentration of abilities and efforts. In principle, and according to the very nature of art—according to its flexibility and multifacetedness—the elite and the popular can coexist in a single work of literature: in successful cases, indeed, that work may be multileveled, written in such a way that it is accessible and satisfactory concurrently for readers of diverse levels of understanding and perception; and if a person experiences an elevation of level over time, he reads the same book with a newer understanding. Failure in achieving this is hardly preordained; but the author has to rise above the day-to-day demands of the publishing market, above calculations of assured near-term success.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Tuesday Poem

…..Motion

Most motion now is at a speed no Roman

or enlightened despot ever dreamed

as truth. The landscape we see we miss;

The oceans we cross we overlook;

The accelerations of word and style

Disguise the flat art we flirt with

The thoughts we dispose of after use.

Speed in this palliative world

Amounts to no executive privilege

Nor does the distance we devour

Sustain us. We dream faster

Than we travel, and the dreams

Speed back to what they meant

When sceptic, wise and mortal Socrates,

Lay paralyzed at the apex of his argument.

by John Bruce

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Monday, March 10, 2025

The Liquid Music of Language

Charlotte Rogers in the Los Angeles Review of Books:

“If there is one feature that defines the human condition, it is language.” This pronouncement appears on the dust jacket of the new memoir by the linguist Julie Sedivy, Linguaphile: A Life of Language Love, but the idea dates back at least to Aristotle, who asserted that what distinguishes humans from other creatures is “logos,” our ability to think rationally and persuade others through language.

“If there is one feature that defines the human condition, it is language.” This pronouncement appears on the dust jacket of the new memoir by the linguist Julie Sedivy, Linguaphile: A Life of Language Love, but the idea dates back at least to Aristotle, who asserted that what distinguishes humans from other creatures is “logos,” our ability to think rationally and persuade others through language.

If language defines the human condition, then Sedivy is superhuman: she spoke five languages before kindergarten and learned to read without ever being taught how. She expresses the joyful rush of comprehension with a profusion of aquatic similes: learning a new word as a child is like catching “fish” amid “flashes of substance and meaning in the liquidity of language flowing all around [her].” Sedivy traces the human lifespan through the prism of language, from the way newborns suck on a pacifier more vigorously when they hear their mother tongue to her own sensual pleasure at sucking on beautiful words “like fruit drops” and the surprising ways vocabulary continues to grow in old age. Linguaphile is a passionate and occasionally zany paean to Aristotle’s logos, roaming freely over literature and the science of language acquisition. These meditations occasionally converge in hilarious ways: at one point, Sedivy imagines linguists in a lab fitting Virginia Woolf with an eye-tracking helmet to observe how the writer’s vision would show her nimble mind parsing a word’s multiple meanings.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

For years, I practised medicine with cool certainty, comfortable with life-and-death decisions. Then, one day, I couldn’t

Ronald W Dworkin at Aeon:

Several years ago, I left my medical practice for a long vacation. On the morning of my first day back, my alarm went off. I pushed the button in and, for a few minutes, lay with the light off. Then, one at a time, I lowered my feet to the floor. The slow process that would transform me back into an anaesthesiologist had begun.

Several years ago, I left my medical practice for a long vacation. On the morning of my first day back, my alarm went off. I pushed the button in and, for a few minutes, lay with the light off. Then, one at a time, I lowered my feet to the floor. The slow process that would transform me back into an anaesthesiologist had begun.

But something was wrong. I felt uneasy about my ability to perform my duties as a physician. Some kind of inner harmony was gone. Before my vacation, I had enjoyed the pleasure of working along a single groove, endlessly repeating surgical cases with unwearied regularity, and making snap decisions with confidence. The unexpected had never really startled me, and, at times, I even hoped for something out of the ordinary. Now something was different – off. I was filled with doubt, born of I knew not where, to which I returned unceasingly. How was this possible? One day I was perfectly fine, and now, after just a few weeks away, confidence and sureness were gone. Simply put, I had lost my professional intuition. Although that explanation may seem imprecise, intuition is real, and, without it, experts lose their bearings. What had once seemed sure and certain for them becomes a question for enquiry.

Researchers have long recognised intuition’s relevance to professional judgment.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Government Knows AGI is Coming

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Nuclear-Level Risk of Superintelligent AI

Dan Hendrycks and Eric Schmidt in Time:

In the nuclear age that followed Oppenheimer’s creation of the atomic bomb, America’s technological monopoly lasted roughly four years before Soviet scientists achieved parity. This balance of terror, combined with the unprecedented destructive potential of these new weapons, gave rise to mutual assured destruction (MAD)—a deterrence framework that, despite its flaws, prevented catastrophic conflict for decades. The stakes of nuclear retaliation discourage each side from striking first, ultimately allowing for a tense but stable standoff.

In the nuclear age that followed Oppenheimer’s creation of the atomic bomb, America’s technological monopoly lasted roughly four years before Soviet scientists achieved parity. This balance of terror, combined with the unprecedented destructive potential of these new weapons, gave rise to mutual assured destruction (MAD)—a deterrence framework that, despite its flaws, prevented catastrophic conflict for decades. The stakes of nuclear retaliation discourage each side from striking first, ultimately allowing for a tense but stable standoff.

Today’s AI competition has the potential to be even more complex than the nuclear era that preceded it, in part because AI is a broadly applicable technology that touches nearly every domain, from medicine to finance to defense. Powerful AI may even automate AI research itself, giving the first nation to possess it an expanding lead in both defensive and offensive power. A nation on the cusp of wielding superintelligent AI, an AI vastly smarter than humans in virtually every domain, would amount to a national security emergency for its rivals, who might turn to threatening sabotage rather than cede power. If we are heading towards a world with superintelligence, we must be clear-eyed about the potential for geopolitical instability.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Democracy, War, and Identity

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Return Of Brutalism

Daniel Brook at The Nation:

To enter the Rudolph retrospective at the Met is to be seduced. Enveloped in the museum’s 20th-century art galleries, the clean lines and daring spirit of Rudolph’s drawings place him comfortably in the company of the modern masters nearby. His geometric precision and imaginative forms echo Russian Constructivists like El Lissitzky. Exhibition photographs of Rudolph’s built works alluringly capture the interplay between light and shadow that animate the interiors and exteriors of his massive concrete structures. One featured building is a levitating layer cake improbably balanced on fluted columns; in another mock-up, a concrete snake of triangular apartment buildings slithers its way across Manhattan.

To enter the Rudolph retrospective at the Met is to be seduced. Enveloped in the museum’s 20th-century art galleries, the clean lines and daring spirit of Rudolph’s drawings place him comfortably in the company of the modern masters nearby. His geometric precision and imaginative forms echo Russian Constructivists like El Lissitzky. Exhibition photographs of Rudolph’s built works alluringly capture the interplay between light and shadow that animate the interiors and exteriors of his massive concrete structures. One featured building is a levitating layer cake improbably balanced on fluted columns; in another mock-up, a concrete snake of triangular apartment buildings slithers its way across Manhattan.

But Brutalism’s move from form to function is a journey from utopia to dystopia—a trajectory the curators pointedly ignore. Those photogenic fluted columns are from a parking garage that Rudolph jammed into the once-walkable heart of New Haven. A 1963 Vogue magazine feature, included in the galleries, shows Rudolph, dressed in a snappy suit, standing next to his gas guzzler on the parking garage’s roof.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Horrific Surrealism: Writing on Migration

Viet Thanh Nguyen at The Paris Review:

It is safe to say that perceptions of migrants are contradictory. In their countries of origin, they are sometimes celebrated for having embarked on adventures and sometimes criticized as having abandoned their homes. In the countries of their arrival, they can appear as terrifying threats in another people’s history or be welcomed as fresh blood. If they face hostility and suspicion, migrants might feel the need to insert themselves into their new nation’s chronicles of conquest. The migrant’s heroism can then harmonize with their host nation’s self-image, as well as affirming that nation’s hospitality and generosity.

It is safe to say that perceptions of migrants are contradictory. In their countries of origin, they are sometimes celebrated for having embarked on adventures and sometimes criticized as having abandoned their homes. In the countries of their arrival, they can appear as terrifying threats in another people’s history or be welcomed as fresh blood. If they face hostility and suspicion, migrants might feel the need to insert themselves into their new nation’s chronicles of conquest. The migrant’s heroism can then harmonize with their host nation’s self-image, as well as affirming that nation’s hospitality and generosity.

This is what happens in Jhumpa Lahiri’s short story “The Third and Final Continent,” from her lauded collection The Interpreter of Maladies, which focuses on Indian immigrants to the United States. I admire the formal elegance of much of Lahiri’s writing, especially her short stories, a genre in which she excels and in which I am at my most miserable. I spent seventeen horrible years writing short stories on a similar theme as Lahiri’s, signaled by the title of my book: The Refugees.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Where Are The War Poets ?

C. Day Lewis in All Poetry:

They who in folly or mere greed

They who in folly or mere greed

Enslaved religion, markets, laws,

Borrow our language now and bid

Us to speak up in freedom’s cause.

It is the logic of our times,

No subject for immortal verse –

That we who lived by honest dreams

Defend the bad against the worse.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

‘Scientists will not be silenced’: thousands protest Trump research cuts

From Nature:

Washington DC. Boston, Massachusetts. Denver, Colorado. Seattle, Washington. Trenton, New Jersey

Washington DC. Boston, Massachusetts. Denver, Colorado. Seattle, Washington. Trenton, New Jersey

Thousands of researchers and supporters of science protested in more than 30 cities across the United States and Europe today against actions taken by the administration of US President Donald Trump to cut the US scientific workforce and slash spending on research worldwide. The mood was defiant at many of the rallies, where chants of “Scientists will not be silenced”, “Facts over fear” and “What do we want? Peer review! When do we want it? Now!” were heard.

Quoting musician Bob Marley, Rush Holt Jr, former chief executive of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, told the crowd in Trenton, New Jersey, “get up, stand up”. In the crowd at Boston’s rally, Ana-Maria Vranceanu, a psychologist at Harvard Medical School whose work helps people with dementia, chronic pain and other conditions, said: “This is the time to actually stop this, before things get really bad.” Over the past month, “I’ve been waiting for someone to do something,” said Abraham Flaxman, a global-health metrics researcher at the University of Washington who attended the Seattle rally. But “it’s dawned on me: nobody is coming to save us. We’re going to have to save ourselves.”

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Sunday, March 9, 2025

An Inescapable Past

Shehryar Fazli in The Ideas Letter:

“This was a destruction not of a house but of our history, of my history,” said a veteran of Bangladesh’s 1971 liberation war. He was speaking to me of the destruction on Feb. 5 of the Dhaka home of Sheikh Mujib ur Rahman, Bangladesh’s first leader.

The address, 32 Dhanmondi, is as well known in Bangladesh as 1600 Pennsylvania in the U.S. It is where, in March 1971, Mujib was apprehended by Pakistani troops as they began their violent crackdown in East Pakistan that culminated in a genocide, the third Pakistan-India war, and the birth of a new nation. And it is where, on Aug. 15, 1975, Bangladeshi soldiers slaughtered Prime Minister Mujib and several members of his family in the country’s first military coup. That it now stands in ruins is an indication of how much public anger had accumulated during the 15 years of the increasingly repressive rule under Mujib’s daughter, Sheikh Hasina Wajed, which ended dramatically on Aug. 5, 2024 after weeks of student-led protests.

Hasina had turned 32 Dhanmondi into a memorial for her father. Now exiled in India, where she fled after her fall from power, Hasina is plotting a political comeback. On Feb. 5, marking a gathering of her Awami League party, she planned to give a speech that would condemn Chief Adviser Muhammad Yunus’s interim government and announce her intentions to avenge her ouster. The youth leaders warned that if she spoke they would destroy her father’s house.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

American Strong Gods

An argument for closed societies from the new right… N.S. Lyons in their substack:

I believe Donald Trump marks the overdue end of the Long Twentieth Century.

The 125 years between the French Revolution in 1789 and the outbreak of WWI in 1914 was later described as the “Long Nineteenth Century.” The phrase recognized that to speak of “the nineteenth century” was to describe far more than a specific hundred-year span on the calendar; it was to capture the whole spirit of an age: a rapturous epoch of expansion, empire, and Enlightenment, characterized by a triumphalist faith in human reason and progress. That lingering historical spirit, distinct from any before or after, was extinguished in the trenches of the Great War. After the cataclysm, an interregnum that ended only with the conclusion of WWII, everything about how the people of Western civilization perceived and engaged with the world – politically, psychologically, artistically, spiritually – had changed.

R.R. Reno opens his 2019 book Return of the Strong Gods by quoting a young man who laments that “I am twenty-seven years old and hope to live to see the end of the twentieth century.” His paradoxical statement captures how the twentieth century has also extended well past its official sell-by date in the year 2000. Our Long Twentieth Century had a late start, fully solidifying only in 1945, but in the 80 years since its spirit has dominated our civilization’s whole understanding of how the world is and should be. It has set all of our society’s fears, values, and moral orthodoxies. And, through the globe-spanning power of the United States, it has shaped the political and cultural order of the rest of the world as well.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The attention economy is devouring politics

Henry Farrell over at his substack, Programmable Mutter:

When Ezra Klein and Chris Hayes talked recently about Chris’s new book, The Siren’s Call: How Attention Became the World’s Most Endangered Resource, my friend John Sides took polite exception. His criticism doesn’t seem to be available online (it was in the newsletter for Good Authority) but his broad claim was that we should not pay too much attention to attention. Even if Trump and other Republicans are good at getting eyeballs, they may not win enough votes, and might even alienate people. Attracting attention may end up being a bad idea.

Good Authority is a political science publication* and John was making a case for the established wisdoms of political science. It was a good case, and one which, I am pretty sure that Chris would largely agree with (he says some pretty similar things in the book). But in the interests of good argument, I’d like to keep the dialectic going, counter-claiming that standard political science could greatly benefit from engaging with the ideas that Chris and Ezra batted around in their conversation, and that are discussed in greater depth in Chris’s book. Both podcast and book highlight problems that political scientists are bad at understanding. When political scientists think about attention, they usually rely on survey analysis and similar static means of capturing what citizens say about their attitudes. They do not, with occasional exceptions think much about the flows involved in therelationship between attention, technology and bandwidth.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

David Johansen (1950 – 2025) Lead Singer Of New York Dolls

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Paradox of Being a Good Person – George Orwell’s Warning to the World

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.