From iai:

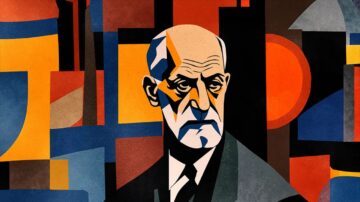

We associate Freud with the repression of thoughts and feelings. But he also described a subtler defense: recognizing an uncomfortable truth, yet acting as if it didn’t matter—a phenomenon he called disavowal. In this interview, philosopher Alenka Zupančič, a close collaborator of Slavoj Žižek, argues that disavowal is the key to understanding our political paralysis. From climate change to populism to the performative outrage of social media, Zupančič says the problem isn’t that we deny reality—it’s that we acknowledge it endlessly and keep doing nothing.

We associate Freud with the repression of thoughts and feelings. But he also described a subtler defense: recognizing an uncomfortable truth, yet acting as if it didn’t matter—a phenomenon he called disavowal. In this interview, philosopher Alenka Zupančič, a close collaborator of Slavoj Žižek, argues that disavowal is the key to understanding our political paralysis. From climate change to populism to the performative outrage of social media, Zupančič says the problem isn’t that we deny reality—it’s that we acknowledge it endlessly and keep doing nothing.

Oliver Adelson: Your latest book spans politics, philosophy, psychology, and more, but there’s one concept that you think is essential for making sense of all these areas: disavowal. What is disavowal, and why is it so key for understanding our predicament?

Alenka Zupančič: It’s something that I started to think about really intensely a few years ago. So it’s not that it’s been with me the whole time, but I think it captures something essential—as you put it—about this time. And it’s a very interesting concept, because we are used to this other concept, which is simple denial. You know, denial of climate change, denial of this or that. But disavowal functions in a much more perverse way. Namely, by first fully acknowledging some fact—“I know very well that this is how things are”—but then going on as if this knowledge didn’t really matter or register. So in practice, you just go on as before. And I think this is even more prevalent in our response to different social predicaments than simple denial.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

W

W I remember the vogue in the ’60s and ’70s for critical essays predicting the imminent “death of the novel.” In

I remember the vogue in the ’60s and ’70s for critical essays predicting the imminent “death of the novel.” In  It’s not that the AI companies are growing their computing power slowly — surprise at the lack of compute put into new training reflects how aggressively they’ve scaled until now. Releasing a one hundred times larger model every two years would demand a tenfold increase in capacity each year, which, You says, is unrealistic. A new model every three years, he says, might be feasible, though that still requires an ambitious five-fold increase in compute every year.

It’s not that the AI companies are growing their computing power slowly — surprise at the lack of compute put into new training reflects how aggressively they’ve scaled until now. Releasing a one hundred times larger model every two years would demand a tenfold increase in capacity each year, which, You says, is unrealistic. A new model every three years, he says, might be feasible, though that still requires an ambitious five-fold increase in compute every year. In 1987, Lei Jun 雷军 was a 21-year-old student in Wuhan University’s computer science program. The book that had set his imagination alight was Fire in the Valley 硅谷之火, which chronicles the evolution of 1970s homebrew hacker culture into global titans like Apple, Microsoft, and IBM. The heroes of that story, of course, were visionaries like Steve Jobs. Lei Jun’s trajectory — he founded

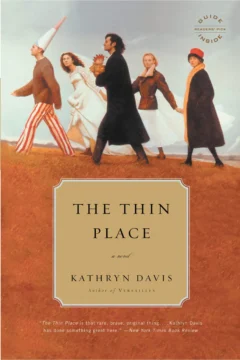

In 1987, Lei Jun 雷军 was a 21-year-old student in Wuhan University’s computer science program. The book that had set his imagination alight was Fire in the Valley 硅谷之火, which chronicles the evolution of 1970s homebrew hacker culture into global titans like Apple, Microsoft, and IBM. The heroes of that story, of course, were visionaries like Steve Jobs. Lei Jun’s trajectory — he founded A few years after I first read The Thin Place, I found myself interviewing Davis for an issue of The Review of Contemporary Fiction, which I was editing at the time. We talked then, as we still talk now, about writing and animals and the city of Philadelphia, where part of my family is from, and where Davis was born on November 13, 1946. Her childhood in a semidetached house on Woodale Road, at the edge of the affluent suburb of Chestnut Hill, Pennsylvania, has found its way into many of her books. It’s there most directly in the haunted house in Hell (1998), the suburban street in Duplex, and the shared childhood memories of the mysterious “we” who narrate The Silk Road (2019). But once you have entered the labyrinth of Davis’s work, you begin to see it, or sense it, around every corner: an atmosphere of dread ruled by the rituals of parents and the patterns of convention—a place where the important things go unsaid or are spoken in code so that if the children overhear, they won’t understand. A place that anybody in their right mind would try to escape.

A few years after I first read The Thin Place, I found myself interviewing Davis for an issue of The Review of Contemporary Fiction, which I was editing at the time. We talked then, as we still talk now, about writing and animals and the city of Philadelphia, where part of my family is from, and where Davis was born on November 13, 1946. Her childhood in a semidetached house on Woodale Road, at the edge of the affluent suburb of Chestnut Hill, Pennsylvania, has found its way into many of her books. It’s there most directly in the haunted house in Hell (1998), the suburban street in Duplex, and the shared childhood memories of the mysterious “we” who narrate The Silk Road (2019). But once you have entered the labyrinth of Davis’s work, you begin to see it, or sense it, around every corner: an atmosphere of dread ruled by the rituals of parents and the patterns of convention—a place where the important things go unsaid or are spoken in code so that if the children overhear, they won’t understand. A place that anybody in their right mind would try to escape. In Some Notes on Mediated Time – one of three completely new essays in the collection – Smith recalls how the “dreamy, slo-mo world” of her 1980s childhood gave way, within a generation, to the “anxious, permanent now” of social media. If you lived through that transition, you don’t have to be very old to feel ancient. When this estrangement is compounded by the ordinary anxieties of ageing, cultural commentary becomes inflected with self-pity. Smith’s identification with the protagonist of

In Some Notes on Mediated Time – one of three completely new essays in the collection – Smith recalls how the “dreamy, slo-mo world” of her 1980s childhood gave way, within a generation, to the “anxious, permanent now” of social media. If you lived through that transition, you don’t have to be very old to feel ancient. When this estrangement is compounded by the ordinary anxieties of ageing, cultural commentary becomes inflected with self-pity. Smith’s identification with the protagonist of  ‘J

‘J In 1990, when Julia Ioffe was 7 years old, her family left a collapsing Soviet Union for suburban Maryland. Her new classmates never let her forget that she was the “weird Russian girl,” but the disdain, she makes clear, was mutual. Growing up, she looked down on American kids who bragged about seeing a Broadway musical or vacationing in Florida. Ioffe’s idea of a good time was going to the opera and reading Pushkin.

In 1990, when Julia Ioffe was 7 years old, her family left a collapsing Soviet Union for suburban Maryland. Her new classmates never let her forget that she was the “weird Russian girl,” but the disdain, she makes clear, was mutual. Growing up, she looked down on American kids who bragged about seeing a Broadway musical or vacationing in Florida. Ioffe’s idea of a good time was going to the opera and reading Pushkin. In talks leading up to the cease-fire deal between Hamas and Israel, President Trump

In talks leading up to the cease-fire deal between Hamas and Israel, President Trump