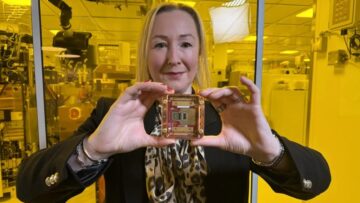

Zoe Kleinman in BBC:

There’s an old adage among tech journalists like me – you can either explain quantum accurately, or in a way that people understand, but you can’t do both. That’s because quantum mechanics – a strange and partly theoretical branch of physics – is a fiendishly difficult concept to get your head around. It involves tiny particles behaving in weird ways. And this odd activity has opened up the potential of a whole new world of scientific super power. Its mind-boggling complexity is probably a factor in why quantum has ended up with a lower profile than tech’s current rockstar – artificial intelligence (AI). This is despite a steady stream of recent big quantum announcements from tech giants like Microsoft and Google among others.

There’s an old adage among tech journalists like me – you can either explain quantum accurately, or in a way that people understand, but you can’t do both. That’s because quantum mechanics – a strange and partly theoretical branch of physics – is a fiendishly difficult concept to get your head around. It involves tiny particles behaving in weird ways. And this odd activity has opened up the potential of a whole new world of scientific super power. Its mind-boggling complexity is probably a factor in why quantum has ended up with a lower profile than tech’s current rockstar – artificial intelligence (AI). This is despite a steady stream of recent big quantum announcements from tech giants like Microsoft and Google among others.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

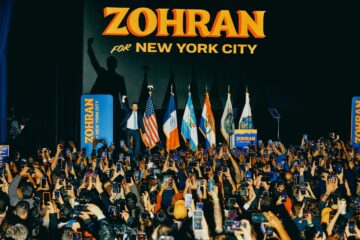

t’s ancient history now, but when Zohran Mamdani first entertained the notion of running for mayor, he imagined himself running against Eric Adams. It was 2021, and Adams had just won a squeaker of a primary, convincing New Yorkers that what they needed in the post-COVID moment was a swaggering ex-cop who believed in good old-fashioned law and order. This summer, while I was reporting a

t’s ancient history now, but when Zohran Mamdani first entertained the notion of running for mayor, he imagined himself running against Eric Adams. It was 2021, and Adams had just won a squeaker of a primary, convincing New Yorkers that what they needed in the post-COVID moment was a swaggering ex-cop who believed in good old-fashioned law and order. This summer, while I was reporting a  O

O T

T

Zohran Mamdani, as most readers know by now, is the son of a filmmaker, Mira Nair. His parents met while she was working on Mississippi Masala (1992); his father, Mahmood Mamdani, is a professor of international affairs and anthropology who had lived through the events from the 1970s described in the film.

Zohran Mamdani, as most readers know by now, is the son of a filmmaker, Mira Nair. His parents met while she was working on Mississippi Masala (1992); his father, Mahmood Mamdani, is a professor of international affairs and anthropology who had lived through the events from the 1970s described in the film. Of all the sins that might damn your soul for eternity, mumbling is probably pretty far down the list. Still, in medieval Europe, there was a demon for that:

Of all the sins that might damn your soul for eternity, mumbling is probably pretty far down the list. Still, in medieval Europe, there was a demon for that:

Mr. Mamdani, who campaigned on sweeping promises, can build a more positive legacy by focusing on tangible accomplishments. He should take notes from successful mayors, moderate and progressive alike, including

Mr. Mamdani, who campaigned on sweeping promises, can build a more positive legacy by focusing on tangible accomplishments. He should take notes from successful mayors, moderate and progressive alike, including  LONG BEFORE ELON

LONG BEFORE ELON  “Go ahead, tell the end, but please don’t tell the beginning!” begs the movie poster for the 1966 film Gambit. Why would the filmmakers prefer to blow the ending rather than beginning?

“Go ahead, tell the end, but please don’t tell the beginning!” begs the movie poster for the 1966 film Gambit. Why would the filmmakers prefer to blow the ending rather than beginning? When forests are cleared, wetlands drained, and slopes destabilized, entire ecosystems lose their balance. Floods, landslides, and erosion then hit both communities and wildlife alike.

When forests are cleared, wetlands drained, and slopes destabilized, entire ecosystems lose their balance. Floods, landslides, and erosion then hit both communities and wildlife alike. You remember the scene: A camera at a Coldplay concert is showing audience members enjoying the show, with lead singer Chris Martin making a few friendly comments about each fan. The camera cuts to an attractive middle-aged couple in the midst of a cute embrace, with the man holding the woman from behind as they sway to the music. Then the couple spots the Jumbotron, and a perfectly choreographed series of panicked actions unfolds. The woman, shocked, covers her face, and turns away from the camera. The man dives to his left, out of the camera’s view. A younger woman, sitting behind them, and evidently in the know about what is happening, comes into view, the look on her face a poetic mix of horror and glee. “Oh, what?” Martin comments. “Either they’re having an affair or they’re just very shy.”

You remember the scene: A camera at a Coldplay concert is showing audience members enjoying the show, with lead singer Chris Martin making a few friendly comments about each fan. The camera cuts to an attractive middle-aged couple in the midst of a cute embrace, with the man holding the woman from behind as they sway to the music. Then the couple spots the Jumbotron, and a perfectly choreographed series of panicked actions unfolds. The woman, shocked, covers her face, and turns away from the camera. The man dives to his left, out of the camera’s view. A younger woman, sitting behind them, and evidently in the know about what is happening, comes into view, the look on her face a poetic mix of horror and glee. “Oh, what?” Martin comments. “Either they’re having an affair or they’re just very shy.” In a 1990 review

In a 1990 review How can whole societies come to believe that the dead walk among them? Understanding that requires moving beyond theoretical approaches and engaging with tangible human communities and their world-views. We will first visit two very different societies in which the veil between life and death has been thin. The dead have been close: sometimes to be revered, sometimes to be feared, but regularly to be interacted with, if not unambiguously in a bodily form. Both case-studies manifest an endemic layer of anxiety, capable of intensifying under stress into something more concentrated and physical.

How can whole societies come to believe that the dead walk among them? Understanding that requires moving beyond theoretical approaches and engaging with tangible human communities and their world-views. We will first visit two very different societies in which the veil between life and death has been thin. The dead have been close: sometimes to be revered, sometimes to be feared, but regularly to be interacted with, if not unambiguously in a bodily form. Both case-studies manifest an endemic layer of anxiety, capable of intensifying under stress into something more concentrated and physical.