Taffy Brodesser-Akner in The New York Times:

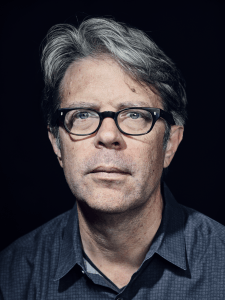

Jonathan Franzen now lives in a humble, perfectly nice two-story house in Santa Cruz, Calif., on a street that looks exactly like a lot of other streets in America and that, save for a few cosmetic choices, looks exactly like every other house on the block. Santa Cruz, he says, is a “little pocket of the ’70s that persisted.” Inside his house, there is art of birds — paintings and drawings and figurines. Outside, in the back, there are actual birds, and a small patio, with a four-person wrought-iron dining set, and beyond that, a shock: a vast, deep ravine, which you would never guess existed behind the homes on such a same-looking street, but there it is. There is so much depth and flora to it, so much nature, so many birds — whose species Franzen names as they whiz by our faces — that you almost don’t notice the ocean beyond.

Jonathan Franzen now lives in a humble, perfectly nice two-story house in Santa Cruz, Calif., on a street that looks exactly like a lot of other streets in America and that, save for a few cosmetic choices, looks exactly like every other house on the block. Santa Cruz, he says, is a “little pocket of the ’70s that persisted.” Inside his house, there is art of birds — paintings and drawings and figurines. Outside, in the back, there are actual birds, and a small patio, with a four-person wrought-iron dining set, and beyond that, a shock: a vast, deep ravine, which you would never guess existed behind the homes on such a same-looking street, but there it is. There is so much depth and flora to it, so much nature, so many birds — whose species Franzen names as they whiz by our faces — that you almost don’t notice the ocean beyond.

He had been reluctant to move here. He played a game of chicken with the woman he calls his “spouse equivalent” (“I hate the word ‘partner’ so much”), the writer Kathryn Chetkovich, telling her that he would never live here and that she should instead move to New York, where he was living in the Yorkville section of the Upper East Side. He still keeps an apartment there. He doesn’t miss Yorkville, which he calls the “last middle-class neighborhood in Manhattan,” though he’s pretty sure the new Second Avenue subway will change all that. Things were changing so fast as it was. The stores he loved kept closing. His favorite produce market, owned by a nice Greek couple, had been supplanted by a bank, and the Food Emporium he reluctantly shopped at became a Gristedes that resembled a Soviet-era rations market. But where are you going to live? The Upper West Side? Best of luck. Each east-west block is nearly a quarter of a mile. “You need to bring a pup tent if you’re walking between Central Park West and Columbus Avenue. It’s like, ‘Bring supplies!’ ”

It’s a different world here in Santa Cruz, an easier place to seclude yourself, to find some anonymity. You can interact on your own terms. Franzen and Chetkovich play mixed doubles with their friends and host game nights. They work out with a trainer named Jason twice a week, who was in a truly open adoption in the 1980s, a time when that was almost unheard-of in this country, which Franzen finds very interesting. Jason administers a workout that is “terrible,” though Franzen, who is 58, has grown to love it: push presses, 400-meter flat-out rowing. He likes to fool around on the guitar that sits in a cradle in the living room, “a better guitar than my advanced beginner status deserves,” trying to learn Chuck Berry and Neil Young songs from YouTube demos.

More here.

White House Press Secretary Sarah Sanders went to have dinner

White House Press Secretary Sarah Sanders went to have dinner Early on in the study of quantum computers, computer scientists posed a question whose answer, they knew, would reveal something deep about the power of these futuristic machines. Twenty-five years later, it’s been all but solved. In a paper

Early on in the study of quantum computers, computer scientists posed a question whose answer, they knew, would reveal something deep about the power of these futuristic machines. Twenty-five years later, it’s been all but solved. In a paper  I became aware of his utter lack of vanity. He never adjusted his hair or gave a damn about makeup or a lighting setup.

I became aware of his utter lack of vanity. He never adjusted his hair or gave a damn about makeup or a lighting setup. The B-2 stealth bomber is the world’s most exotic strategic aircraft, a subsonic flying wing meant to be difficult for air defenses to detect—whether by radar or other means—yet capable of carrying nearly the same payload as the massive B-52. It came into service in the late 1990s primarily for use in a potential nuclear war with the Soviet Union, and clearly as a first-strike weapon rather than a retaliatory one. First-strike weapons have destabilizing, not deterrent, effects. It is probably just as well that the stealth bomber was not quite as stealthy as it was meant to be, and was so expensive—at $2.1 billion each—that only 21 were built before Congress refused to pay for more. Nineteen of them are now stationed close to the geographic center of the contiguous United States, in the desolate farmland of central Missouri, at Whiteman Air Force Base. They are part of the 509th Bomb Wing, and until recently were commanded by Brigadier General Paul W. Tibbets IV, whose grandfather dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima. B-2 bombers are still primarily regarded as a nuclear-delivery system, meaning that their crews are by selection the sort of men and women capable of defining success as a precisely flown sortie at the outset of mass annihilation. No one should doubt that, if given the order to launch a nuclear attack, these crews would carry it out. In the meantime, they have occasionally flown missions of a different sort—make-work projects such as saber rattling over the Korean peninsula, and the opening salvos in Serbia, Afghanistan, and Iraq—to tactical advantage without American discomfort.

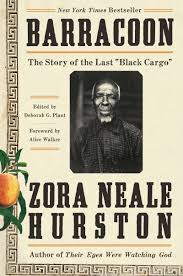

The B-2 stealth bomber is the world’s most exotic strategic aircraft, a subsonic flying wing meant to be difficult for air defenses to detect—whether by radar or other means—yet capable of carrying nearly the same payload as the massive B-52. It came into service in the late 1990s primarily for use in a potential nuclear war with the Soviet Union, and clearly as a first-strike weapon rather than a retaliatory one. First-strike weapons have destabilizing, not deterrent, effects. It is probably just as well that the stealth bomber was not quite as stealthy as it was meant to be, and was so expensive—at $2.1 billion each—that only 21 were built before Congress refused to pay for more. Nineteen of them are now stationed close to the geographic center of the contiguous United States, in the desolate farmland of central Missouri, at Whiteman Air Force Base. They are part of the 509th Bomb Wing, and until recently were commanded by Brigadier General Paul W. Tibbets IV, whose grandfather dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima. B-2 bombers are still primarily regarded as a nuclear-delivery system, meaning that their crews are by selection the sort of men and women capable of defining success as a precisely flown sortie at the outset of mass annihilation. No one should doubt that, if given the order to launch a nuclear attack, these crews would carry it out. In the meantime, they have occasionally flown missions of a different sort—make-work projects such as saber rattling over the Korean peninsula, and the opening salvos in Serbia, Afghanistan, and Iraq—to tactical advantage without American discomfort. Anne Enright recently said of the Irish-American writer Maeve Brennan: “[she] didn’t have to be a woman to be forgotten, but it surely helped”. The same could be said of the African-American writer Zora Neale Hurston (1891-1960), whose extraordinary fictional and anthropological works of the 1930s disappeared into obscurity until revived by feminist scholars in the 1970s. Alongside the better-remembered male writers Langston Hughes and Alain Locke, Hurston was a significant figure of the Harlem Renaissance, though her work was less concerned with the urban “New Negro” than with the rural black subject whose experience she documented alongside her mentor, Franz Boaz, the founder of American anthropology. Her ethnographic scholarship considered the chains that link African, Caribbean, and African-American culture, and she frequently turned to her own home town of Eatonville, Florida for material. She is best-known, however, for her fiction, in particular for her remarkable 1937 novel Their Eyes Were Watching God, which tells the tale of Janie Crawford, an African-American woman born in the aftermath of slavery who must contend not only with white oppression but with black male dominance as well.

Anne Enright recently said of the Irish-American writer Maeve Brennan: “[she] didn’t have to be a woman to be forgotten, but it surely helped”. The same could be said of the African-American writer Zora Neale Hurston (1891-1960), whose extraordinary fictional and anthropological works of the 1930s disappeared into obscurity until revived by feminist scholars in the 1970s. Alongside the better-remembered male writers Langston Hughes and Alain Locke, Hurston was a significant figure of the Harlem Renaissance, though her work was less concerned with the urban “New Negro” than with the rural black subject whose experience she documented alongside her mentor, Franz Boaz, the founder of American anthropology. Her ethnographic scholarship considered the chains that link African, Caribbean, and African-American culture, and she frequently turned to her own home town of Eatonville, Florida for material. She is best-known, however, for her fiction, in particular for her remarkable 1937 novel Their Eyes Were Watching God, which tells the tale of Janie Crawford, an African-American woman born in the aftermath of slavery who must contend not only with white oppression but with black male dominance as well. He worked hard and now can rest. He was one of America’s best-loved poets and won all the literary awards. At eighty-six, he had his first New York Times best seller, with Essays After Eighty, celebrating the indignities of growing old. I once gave him a terrible review, and we didn’t speak for years. “I know I was pissed at you for ten or twelve years,” he wrote. “I take it back. You are good.” He was a judge for the Pulitzer the year I was a finalist. We became friends.

He worked hard and now can rest. He was one of America’s best-loved poets and won all the literary awards. At eighty-six, he had his first New York Times best seller, with Essays After Eighty, celebrating the indignities of growing old. I once gave him a terrible review, and we didn’t speak for years. “I know I was pissed at you for ten or twelve years,” he wrote. “I take it back. You are good.” He was a judge for the Pulitzer the year I was a finalist. We became friends. Soccer makes very little sense at the best of times, and on Monday, in the dying moments of Iran’s World Cup match against Portugal, it made no sense at all. The game had been combative. It was the third and final match day in Group B, and both teams had a chance to advance to the knockout stage; both teams also knew that a bad result could send them home. Elbows flew on every contested header. Bodies strained in ways that made you think of the word “sinew,” possibly for the first time all year. Cristiano Ronaldo, the Portuguese star, winced so hard after bashing a free kick into the Iranian wall that his neck briefly looked like the Rock’s neck.

Soccer makes very little sense at the best of times, and on Monday, in the dying moments of Iran’s World Cup match against Portugal, it made no sense at all. The game had been combative. It was the third and final match day in Group B, and both teams had a chance to advance to the knockout stage; both teams also knew that a bad result could send them home. Elbows flew on every contested header. Bodies strained in ways that made you think of the word “sinew,” possibly for the first time all year. Cristiano Ronaldo, the Portuguese star, winced so hard after bashing a free kick into the Iranian wall that his neck briefly looked like the Rock’s neck. A four-minute film produced for the UnLonely Film Festival and Conference last month featured a young woman who, as a college freshman,

A four-minute film produced for the UnLonely Film Festival and Conference last month featured a young woman who, as a college freshman,

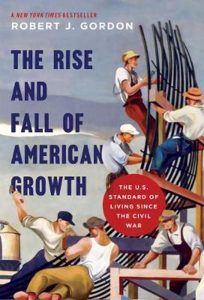

The ability to control electricity so that it arrives in measured doses where and when needed combined with simple steps to improve public sanitation, such as running water, indoor toilets and the removal of the uncountable tons of horse manure that marked major cities before the advent of the internal combustion engine that spurred roads and transportation networks that enabled frozen food to be enjoyed from coast to coast, wrought a step change in living standards unlikely to be repeated.

The ability to control electricity so that it arrives in measured doses where and when needed combined with simple steps to improve public sanitation, such as running water, indoor toilets and the removal of the uncountable tons of horse manure that marked major cities before the advent of the internal combustion engine that spurred roads and transportation networks that enabled frozen food to be enjoyed from coast to coast, wrought a step change in living standards unlikely to be repeated.

Give me a break I mutter. I text—and I text. Incessantly I text. Send money. Now. Send money. More money. You don’t reply. You will. It is Spring and I am young. Everyone around me on the beach is around my age or younger. We are young.

Give me a break I mutter. I text—and I text. Incessantly I text. Send money. Now. Send money. More money. You don’t reply. You will. It is Spring and I am young. Everyone around me on the beach is around my age or younger. We are young.