Text of The W. G. Sebald Lecture on Literary Translation by Arundhati Roy in Raiot:

At a book reading in Kolkata, about a week after my first novel, The God of Small Things was published, a member of the audience stood up and asked, in a tone that was distinctly hostile:

At a book reading in Kolkata, about a week after my first novel, The God of Small Things was published, a member of the audience stood up and asked, in a tone that was distinctly hostile:

Has any writer ever written a masterpiece in an alien language? In a language other than his mother tongue?

I hadn’t claimed to have written a masterpiece (nor to be a “he”), but nevertheless I understood his anger toward a me, a writer who lived in India, wrote in English, and who had attracted an absurd amount of attention. My answer to his question made him even angrier. “Nabokov,” I said. And he stormed out of the hall.

The correct answer to that question today would of course be “algorithms.” Artificial Intelligence, we are told, can write masterpieces in any language and translate them into masterpieces in other languages. As the era that we know, and think we vaguely understand, comes to a close, perhaps we, even the most privileged among us, are just a group of redundant humans gathered here with an arcane interest in language generated by fellow redundants.

Only a few weeks after the mother tongue/masterpiece incident, I was on a live radio show in London. The other guest was an English historian who, in reply to a question from the interviewer, composed a paean to British imperialism. “Even you,” he said, turning to me imperiously,

the very fact that you write in English is a tribute to the British Empire.

Not being used to radio shows at the time, I stayed quiet for a while, as a well-behaved, recently civilized savage should. But then I sort of lost it, and said some extremely hurtful things.

More here.

Born to an Ashkenazi Jewish father and mother of Irish and German descent, science and heredity has long fascinated Carl Zimmer.

Born to an Ashkenazi Jewish father and mother of Irish and German descent, science and heredity has long fascinated Carl Zimmer.

Cavell, rather than being the type of all college professors, turned out to be unique. His tutelage at that time seemed the big experience of my life, and I can’t say that it wasn’t, even now. I was afraid of him, personally—afraid, I mean, of damaging the relation by something personal. I went in later years to his lectures on aesthetics, attended his screenings of operas and films, tried to focus on sessions on Wittgenstein, on language and epistemology.

Cavell, rather than being the type of all college professors, turned out to be unique. His tutelage at that time seemed the big experience of my life, and I can’t say that it wasn’t, even now. I was afraid of him, personally—afraid, I mean, of damaging the relation by something personal. I went in later years to his lectures on aesthetics, attended his screenings of operas and films, tried to focus on sessions on Wittgenstein, on language and epistemology. In July of 2008, as a national broadcast correspondent, I reported on environmental conditions in Newtok, a remote community of roughly 400 Yup’ik people in Northwest Alaska. Newtok was losing forty to a hundred feet of coastline a year to erosion, and sinking because of “permafrost” that is no longer permanent, the direct result of a warming climate. Flooding threatened homes, the school, and the only supply of clean water. I chose to report on Newtok because the community was actively working on a relocation plan after voting to move to higher, more stable ground. My story compared the actions of Newtok with Kivalina, an Inupiaq community of the same size situated on a barrier island further north. Kivalina faced similar conditions and had filed suit that same year against ExxonMobil Corp. for damages caused by climate change.

In July of 2008, as a national broadcast correspondent, I reported on environmental conditions in Newtok, a remote community of roughly 400 Yup’ik people in Northwest Alaska. Newtok was losing forty to a hundred feet of coastline a year to erosion, and sinking because of “permafrost” that is no longer permanent, the direct result of a warming climate. Flooding threatened homes, the school, and the only supply of clean water. I chose to report on Newtok because the community was actively working on a relocation plan after voting to move to higher, more stable ground. My story compared the actions of Newtok with Kivalina, an Inupiaq community of the same size situated on a barrier island further north. Kivalina faced similar conditions and had filed suit that same year against ExxonMobil Corp. for damages caused by climate change. Old houses are full of holes. Creatures sneak into the living room. A summer ago, a garter snake entered and slithered across my living room. I stepped on its head and threw it outside. The same year, I discovered a visitor who became my favorite for persistence. A chipmunk took up residence and remained on the first floor for two or three months. Every day I would hear chirping, at first sounding like an electronic signal. Then the chipmunk came into sight, pausing with its paws tucked or folded before it, I suppose sustained by my cat’s kibble and water. As for my cat, she stared at it intently, fascinated. My housekeeper, Carole, bought a tiny Havahart trap and baited it with whatever we imagined was a chipmunk treat. Every morning the bait was gone, but so was the chipmunk. One morning the creature skittered from the kitchen into the toolshed, where the door showed a wide space at its bottom, and never appeared again. I felt abandoned. When autumn descended into winter, I walked into the cluttered dining room, never used in old age, and smelled something rotten in a box of unsorted snapshots. Under a layer of pictures I found the small body of our chipmunk. It had not escaped after all. With a paper towel I picked it up, rigid and almost weightless, and threw it from the door as far as I could. Next morning when I opened the door to pick up the newspaper, half of his small mummified corpse lay beside the door.

Old houses are full of holes. Creatures sneak into the living room. A summer ago, a garter snake entered and slithered across my living room. I stepped on its head and threw it outside. The same year, I discovered a visitor who became my favorite for persistence. A chipmunk took up residence and remained on the first floor for two or three months. Every day I would hear chirping, at first sounding like an electronic signal. Then the chipmunk came into sight, pausing with its paws tucked or folded before it, I suppose sustained by my cat’s kibble and water. As for my cat, she stared at it intently, fascinated. My housekeeper, Carole, bought a tiny Havahart trap and baited it with whatever we imagined was a chipmunk treat. Every morning the bait was gone, but so was the chipmunk. One morning the creature skittered from the kitchen into the toolshed, where the door showed a wide space at its bottom, and never appeared again. I felt abandoned. When autumn descended into winter, I walked into the cluttered dining room, never used in old age, and smelled something rotten in a box of unsorted snapshots. Under a layer of pictures I found the small body of our chipmunk. It had not escaped after all. With a paper towel I picked it up, rigid and almost weightless, and threw it from the door as far as I could. Next morning when I opened the door to pick up the newspaper, half of his small mummified corpse lay beside the door. Books are so intimate, somehow, and perhaps this is one reason why so many of the current glut of reading memoirs leave me cold. Even as they strain for this sense of disclosure – don’t you feel like this, too? they ask – their tone is proprietorial, hellbent on exceptionality (I love the Brontës even more than you). You would, I think, accept this from a lover, but not from a writer you’ve never met – unless, I will now add, that writer happens to be Edmund White, the tone of whose new book, The Unpunished Vice: A Life of Reading, quite often resembles the gentle whisper of a sweetheart. Ownership, you see, is not at all his style. In fact, he doesn’t claim always to understand the books that he loves most. “I’ve read it 10 times, though I’m none the wiser for it,” he writes of

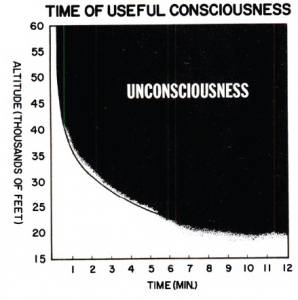

Books are so intimate, somehow, and perhaps this is one reason why so many of the current glut of reading memoirs leave me cold. Even as they strain for this sense of disclosure – don’t you feel like this, too? they ask – their tone is proprietorial, hellbent on exceptionality (I love the Brontës even more than you). You would, I think, accept this from a lover, but not from a writer you’ve never met – unless, I will now add, that writer happens to be Edmund White, the tone of whose new book, The Unpunished Vice: A Life of Reading, quite often resembles the gentle whisper of a sweetheart. Ownership, you see, is not at all his style. In fact, he doesn’t claim always to understand the books that he loves most. “I’ve read it 10 times, though I’m none the wiser for it,” he writes of  Since 1900, average life expectancy around the globe

Since 1900, average life expectancy around the globe

Why do people care about sport? With hundreds of millions of human beings (myself included) obsessively following the world cup that is being played out in Russia, it’s a good time to reflect once again on this perennially interesting question.

Why do people care about sport? With hundreds of millions of human beings (myself included) obsessively following the world cup that is being played out in Russia, it’s a good time to reflect once again on this perennially interesting question.

The German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900) pursued two main themes in his work, one now familiar, even commonplace in modernity, the other still under-appreciated, often ignored. The familiar Nietzsche is the “existentialist”, who diagnoses the most profound cultural fact about modernity: “the death of God”, or more exactly, the collapse of the possibility of reasonable belief in God. Belief in God – in transcendent meaning or purpose, dictated by a supernatural being – is now incredible, usurped by naturalistic explanations of the evolution of species, the behaviour of matter in motion, the unconscious causes of human behaviours and attitudes, indeed, by explanations of how such a bizarre belief arose in the first place. But without God or transcendent purpose, how can we withstand the terrible truths about our existence, namely, its inevitable suffering and disappointment, followed by death and the abyss of nothingness?

The German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900) pursued two main themes in his work, one now familiar, even commonplace in modernity, the other still under-appreciated, often ignored. The familiar Nietzsche is the “existentialist”, who diagnoses the most profound cultural fact about modernity: “the death of God”, or more exactly, the collapse of the possibility of reasonable belief in God. Belief in God – in transcendent meaning or purpose, dictated by a supernatural being – is now incredible, usurped by naturalistic explanations of the evolution of species, the behaviour of matter in motion, the unconscious causes of human behaviours and attitudes, indeed, by explanations of how such a bizarre belief arose in the first place. But without God or transcendent purpose, how can we withstand the terrible truths about our existence, namely, its inevitable suffering and disappointment, followed by death and the abyss of nothingness? In 1890, just over six thousand people lived in the damp lowlands of south

In 1890, just over six thousand people lived in the damp lowlands of south  EARLY IN THE MORNING

EARLY IN THE MORNING