Category: Recommended Reading

David Goldblatt (1930 – 2018)

Sunday Poem

The Physics of Angels

I suspect the world remembers everything—

time and bones and words flung together,

and me in it, suspecting. If we can believe

in photons—entities that possess movement

but not mass, and if the spirit, too

is made of light—then who am I to say

I haven’t lived before—or you,

and thus this tenderness?

Who am I to doubt that grace

is elemental like fire—or that souls

have no need of us, finally?

by Trish Crapo

from Walk Through Paradise Backward

Slate Roof Publishing 2004

Should You Tell Everyone They’re Honest? People try to live up to their labels

Christian B. Miller in Nautilus:

Here is the predicament that most of us seem to be in. We are not virtuous people. We simply do not have characters that are good enough to qualify as honest, compassionate, wise, courageous, and the like. We are not vicious people either—dishonest, callous, foolish, cowardly, and so forth. Rather we have a mixed character with some good sides and some bad sides. This is the most plausible interpretation of what psychology tells us. It is also true to our lived experience in the world. Those are the facts as I see them. Now comes the value judgment—this is a real shame. It is very unfortunate that our characters are this way. It is a good thing—indeed, a very good thing—to be a good person. Excellence of character, or being virtuous, is what we should all strive for. Admittedly, the news is not all bad. It would be a lot worse if most of us were vicious people. Imagine what it would be like to live in a world full of mostly cruel, self-centered, dishonest, and hateful people. It would be hell on earth.

Here is the predicament that most of us seem to be in. We are not virtuous people. We simply do not have characters that are good enough to qualify as honest, compassionate, wise, courageous, and the like. We are not vicious people either—dishonest, callous, foolish, cowardly, and so forth. Rather we have a mixed character with some good sides and some bad sides. This is the most plausible interpretation of what psychology tells us. It is also true to our lived experience in the world. Those are the facts as I see them. Now comes the value judgment—this is a real shame. It is very unfortunate that our characters are this way. It is a good thing—indeed, a very good thing—to be a good person. Excellence of character, or being virtuous, is what we should all strive for. Admittedly, the news is not all bad. It would be a lot worse if most of us were vicious people. Imagine what it would be like to live in a world full of mostly cruel, self-centered, dishonest, and hateful people. It would be hell on earth.

Nevertheless, at this point we are confronted with a significant gap.

What strategies are there to try to develop a better character, and which of these strategies show substantial promise? In my book The Character Gap: How Good Are We?, I consider a number of different strategies. One I find quite interesting is what we might call “virtue labeling.” Suppose you come to believe, as I do, that most of the people we know do not have any of the virtues. So your friend, your boss, your neighbor … you need to change your opinion of all of them. Now here is the interesting idea—even with this new outlook firmly in mind, you should still go ahead and call them honest people next time you see them. You should still praise them for being compassionate. You should go out of your way to comment on their courage.

What strategies are there to try to develop a better character, and which of these strategies show substantial promise? In my book The Character Gap: How Good Are We?, I consider a number of different strategies. One I find quite interesting is what we might call “virtue labeling.” Suppose you come to believe, as I do, that most of the people we know do not have any of the virtues. So your friend, your boss, your neighbor … you need to change your opinion of all of them. Now here is the interesting idea—even with this new outlook firmly in mind, you should still go ahead and call them honest people next time you see them. You should still praise them for being compassionate. You should go out of your way to comment on their courage.

Why would you do such a thing? Isn’t that just wrong?

More here.

Saturday, June 30, 2018

Benjamin Libet and The Denial of Free Will: How Did a Flawed Experiment Become so Influential?

Steve Taylor in Psychology Today:

You might feel that you have the ability to make choices, decisions and plans – and the freedom to change your mind at any point if you so desire – but many psychologists and scientists would tell you that this is an illusion. The denial of free will is one of the major principles of the materialist worldview that dominates secular western culture. Materialism is the view that only the physical stuff of the world – atoms and molecules and the objects and beings that they constitute – are real. Consciousness and mental phenomena can be explained in terms of neurological processes.

You might feel that you have the ability to make choices, decisions and plans – and the freedom to change your mind at any point if you so desire – but many psychologists and scientists would tell you that this is an illusion. The denial of free will is one of the major principles of the materialist worldview that dominates secular western culture. Materialism is the view that only the physical stuff of the world – atoms and molecules and the objects and beings that they constitute – are real. Consciousness and mental phenomena can be explained in terms of neurological processes.

Materialism developed as a philosophy in the second half of the nineteenth century, as the influence of religion waned. And right from the start, materialists realised from the start the denial of free will was inherent in their philosophy. As one of the most fervent early materialists, T.H. Huxley, stated in 1874, “Volitions do not enter into the chain of causation…The feeling that we call volition is not the cause of a voluntary act, but the symbol of that state of the brain which is the immediate cause.” Here Huxley anticipated the ideas of some modern materialists – such as the psychologist Daniel Wegner – who claim that free will is literally a “trick of the mind.” According to Wegner, “The experience of willing an act arises from interpreting one’s thought as the cause of the act.” In other words, our sense of making choices or decisions is just an awareness of what the brain has already decided for us.

More here.

The momentous transition to multicellular life may not have been so hard after all

Elizabeth Pennisi in Science:

Billions of years ago, life crossed a threshold. Single cells started to band together, and a world of formless, unicellular life was on course to evolve into the riot of shapes and functions of multicellular life today, from ants to pear trees to people. It’s a transition as momentous as any in the history of life, and until recently we had no idea how it happened.

Billions of years ago, life crossed a threshold. Single cells started to band together, and a world of formless, unicellular life was on course to evolve into the riot of shapes and functions of multicellular life today, from ants to pear trees to people. It’s a transition as momentous as any in the history of life, and until recently we had no idea how it happened.

The gulf between unicellular and multicellular life seems almost unbridgeable. A single cell’s existence is simple and limited. Like hermits, microbes need only be concerned with feeding themselves; neither coordination nor cooperation with others is necessary, though some microbes occasionally join forces. In contrast, cells in a multicellular organism, from the four cells in some algae to the 37 trillion in a human, give up their independence to stick together tenaciously; they take on specialized functions, and they curtail their own reproduction for the greater good, growing only as much as they need to fulfill their functions. When they rebel, cancer can break out.

Multicellularity brings new capabilities. Animals, for example, gain mobility for seeking better habitat, eluding predators, and chasing down prey. Plants can probe deep into the soil for water and nutrients; they can also grow toward sunny spots to maximize photosynthesis. Fungi build massive reproductive structures to spread their spores. But for all of multicellularity’s benefits, says László Nagy, an evolutionary biologist at the Biological Research Centre of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences in Szeged, it has traditionally “been viewed as a major transition with large genetic hurdles to it.”

More here.

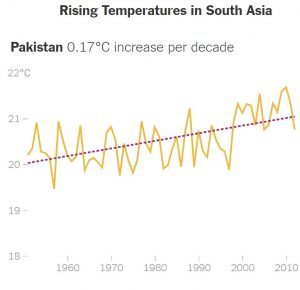

Global Warming in South Asia: 800 Million at Risk

Somini Sengupta and Nadja Popovich in the New York Times:

Climate change could sharply diminish living conditions for up to 800 million people in South Asia, a region that is already home to some of the world’s poorest and hungriest people, if nothing is done to reduce global greenhouse gas emissions, the World Bank warned Thursday in an ominous new study.

Climate change could sharply diminish living conditions for up to 800 million people in South Asia, a region that is already home to some of the world’s poorest and hungriest people, if nothing is done to reduce global greenhouse gas emissions, the World Bank warned Thursday in an ominous new study.

The study looked at all six countries of South Asia, where average annual temperatures are rising steadily and rainfall patterns are already changing. It concentrated on changes in day-to-day weather, rather than sudden-onset natural disasters, and identified “hot spots” where the deterioration is expected to be most severe.

“The analyses reveal that hot spots tend to be more disadvantaged districts, even before the effects of changes in average weather are felt,” the report concluded. “Hot spots are characterized by low household consumption, poor road connectivity, limited access to markets, and other development challenges.”

Unchecked climate change, in other words, would amplify the hardships of poverty.

More here.

Oppression Obsession

The Famously Curmudgeonly and Irascible Harlan Ellison

John Scalzi at The LA Times:

What did I do to deserve a yelling at from the famously curmudgeonly and irascible Harlan Ellison? Well, from 2010 to 2013, I was the president of SFWA, the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America, an organization to which Harlan belonged and which made him one of its Grand Masters in 2006. Harlan believed that as a Grand Master I was obliged to take his call whenever he felt like calling, which was usually late in the evening, as I was Eastern time and he was on Pacific time. So some time between 11 p.m. and 1 a.m., the phone would ring, and “It’s Harlan” would rumble across the wires, and then for the next 30 or so minutes, Harlan Ellison would expound on whatever it was he had a wart on his fanny about, which was sometimes about SFWA-related business, and sometimes just life in general.

What did I do to deserve a yelling at from the famously curmudgeonly and irascible Harlan Ellison? Well, from 2010 to 2013, I was the president of SFWA, the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America, an organization to which Harlan belonged and which made him one of its Grand Masters in 2006. Harlan believed that as a Grand Master I was obliged to take his call whenever he felt like calling, which was usually late in the evening, as I was Eastern time and he was on Pacific time. So some time between 11 p.m. and 1 a.m., the phone would ring, and “It’s Harlan” would rumble across the wires, and then for the next 30 or so minutes, Harlan Ellison would expound on whatever it was he had a wart on his fanny about, which was sometimes about SFWA-related business, and sometimes just life in general.

more here.

Exploring the New Science of Psychedelics

Mick Brown at Literary Review:

For better or worse, Albert Hofmann has a lot to answer for. It was Hofmann, a chemist working for Sandoz Laboratories in Switzerland, who in 1943, in search of a respiratory and circulatory stimulant, inadvertently hit upon a substance called lysergic acid diethylamide, or LSD. Accidentally ingesting some of the substance, Hofmann found himself overcome by ‘an uninterrupted stream of fantastic pictures, extraordinary shapes with intense, kaleidoscopic play of colors’. This was the world’s first acid trip.

For better or worse, Albert Hofmann has a lot to answer for. It was Hofmann, a chemist working for Sandoz Laboratories in Switzerland, who in 1943, in search of a respiratory and circulatory stimulant, inadvertently hit upon a substance called lysergic acid diethylamide, or LSD. Accidentally ingesting some of the substance, Hofmann found himself overcome by ‘an uninterrupted stream of fantastic pictures, extraordinary shapes with intense, kaleidoscopic play of colors’. This was the world’s first acid trip.

It was Hofmann, too, who in 1958 isolated psilocybin, the ingredient found in several species of ‘magic mushrooms’ from Latin America. These had long been used in shamanic rituals, but Hofmann’s breakthrough allowed psilocybin to be easily prepared in the laboratory for clinicians and psychiatrists to use in ‘psychedelic therapy’.

more here.

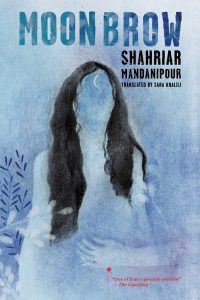

On Reading ‘Moon Brow’

Shohreh Laici at The Quarterly Conversation:

Moon Brow is a story of lust, love, and loss set during three periods of time: Iran’s revolution, the post-revolution and Eight Years War with Iraq, and the post-war era. An Eight Years War veteran, Amir Yamini, who formerly drowned himself in sex and alcohol, is discovered in a hospital for shell-shock victims by his mother and his sister Reyhaneh, having languished there for five years. Suffering from mental injuries caused by the war, Amir is haunted by a woman in his dreams that he calls “Moon Brow” because he can’t see her face. Amir’s attempt to seek the truth of his past brings him to his old friend, Kaveh, who might know what happened in Amir’s past life. The search for a woman he truly loved before going to war takes him to where he lost his left arm—and his wedding ring—during the war. Amir’s relationship with his sister Reyhaneh is one of the best parts of the novel—a true companion, Reyhaneh helps Amir discover the truth of his life before the war. Moon Brow combines Amir’s journey into his past life with the history of Iran, and also it shares the trauma of war as it reveals the victims of Saddam Hussein’s genocidal ideology.

Moon Brow is a story of lust, love, and loss set during three periods of time: Iran’s revolution, the post-revolution and Eight Years War with Iraq, and the post-war era. An Eight Years War veteran, Amir Yamini, who formerly drowned himself in sex and alcohol, is discovered in a hospital for shell-shock victims by his mother and his sister Reyhaneh, having languished there for five years. Suffering from mental injuries caused by the war, Amir is haunted by a woman in his dreams that he calls “Moon Brow” because he can’t see her face. Amir’s attempt to seek the truth of his past brings him to his old friend, Kaveh, who might know what happened in Amir’s past life. The search for a woman he truly loved before going to war takes him to where he lost his left arm—and his wedding ring—during the war. Amir’s relationship with his sister Reyhaneh is one of the best parts of the novel—a true companion, Reyhaneh helps Amir discover the truth of his life before the war. Moon Brow combines Amir’s journey into his past life with the history of Iran, and also it shares the trauma of war as it reveals the victims of Saddam Hussein’s genocidal ideology.

more here.

Sexual Double Standards

Martie Haselton in Edge:

I’m asking myself about double standards a lot lately, in public life and also in science. I’m particularly concerned about double standards in science whereby women’s issues are viewed differently than men’s. We’ve lagged behind in important ways because there is a concern that if we have a biological explanation for women’s behavior, it will smash women up against the glass ceiling, whereas a biological explanation for men’s behavior doesn’t do such a thing. So, we’ve been freer in biomedical science to explore questions about the biological foundations of men’s behavior and less free to explore those questions about women’s behavior. That’s a problem that manifests itself in the lag behind what we understand about men and what we understand about women.

I’m asking myself about double standards a lot lately, in public life and also in science. I’m particularly concerned about double standards in science whereby women’s issues are viewed differently than men’s. We’ve lagged behind in important ways because there is a concern that if we have a biological explanation for women’s behavior, it will smash women up against the glass ceiling, whereas a biological explanation for men’s behavior doesn’t do such a thing. So, we’ve been freer in biomedical science to explore questions about the biological foundations of men’s behavior and less free to explore those questions about women’s behavior. That’s a problem that manifests itself in the lag behind what we understand about men and what we understand about women.

I’ll give you a couple of examples. Men have their bedroom troubles that have been solved, by and large, by pharmaceutical companies, whereas women’s have not. Women’s desires may very well be more complicated than, say, solving a mechanical problem for men, but we just don’t know much. And the options we do have, by way of pharmaceutical interventions, are terrible and nobody wants to use them.

For men, Viagra solved a lot of their bedroom troubles. Woman have something called Flibanserin—a very sexy name. Men can take Viagra within an hour of wanting to have sex, and that will help with erectile dysfunction, whereas Flibanserin, which is supposed to solve some of the problems of women’s sexual desire or lack thereof, has to be taken every day. It makes them lightheaded and prone to passing out, and they can’t drink alcohol when they’re taking it. There’s a real inequality there.

There are a couple of factors to think about here. One involves the bias against understanding the biological factors that underlie women’s behavior because of a sexual double standard, and I can elaborate on that. Another is that males, across animal species, have been viewed as the default and, therefore, the thinking is that if you understand males, you understand females. Even at the cellular level that is not the case. The NIH has now started to recognize that. It is a requirement that clinical trials involve equal numbers of males and females unless there are really good reasons for why a researcher would want to study males to the exclusion of females or females to the exclusion of males.

More here.

Wombs in Revolt

Claire Horn in Avidly:

In the 1970s, Shulamith Firestone wrote: “the end goal of feminist revolution must be […] not just the elimination of male privilege but of the sex distinction itself […] The reproduction of the species by one sex for the benefit of both would be replaced by (or at least the option of) artificial reproduction: children would be born to both sexes equally.” This hopeful if unsettling vision of the artificial womb entices me, a 1970s harbinger of the “gender is over” rallying cry. Firestone’s utopian manifesto, penned in a world where birth control and in vitro fertilisation were new to the reproductive conversation, was buoyed by its relative improbability. Maybe Firestone really believed that the new reproductive technologies of her era heralded the arrival of ectogenesis sometime after. More likely it was the stuff of fantasy, provocatively introduced to challenge readers to reconsider the status quo.

In the 1970s, Shulamith Firestone wrote: “the end goal of feminist revolution must be […] not just the elimination of male privilege but of the sex distinction itself […] The reproduction of the species by one sex for the benefit of both would be replaced by (or at least the option of) artificial reproduction: children would be born to both sexes equally.” This hopeful if unsettling vision of the artificial womb entices me, a 1970s harbinger of the “gender is over” rallying cry. Firestone’s utopian manifesto, penned in a world where birth control and in vitro fertilisation were new to the reproductive conversation, was buoyed by its relative improbability. Maybe Firestone really believed that the new reproductive technologies of her era heralded the arrival of ectogenesis sometime after. More likely it was the stuff of fantasy, provocatively introduced to challenge readers to reconsider the status quo.

But what once felt like fantasy seems increasingly more real. A human pregnancy is 40 weeks of gestation, with any baby born before 37 weeks considered preterm. The point at which a human fetus can survive outside the mother’s womb (otherwise known as “fetal viability”) sat around 28 weeks of gestation when Roe v. Wade was handed down almost exactly forty-five years ago. Today, following progress in neonatal intensive care technologies, viability in most wealthy countries is somewhere between 22 and 26 weeks, depending on the resources available in a given area and hospital. The health of babies born before 28 weeks remains precarious. In April of 2016, however, a group of scientists in Philadelphia developed a partial artificial womb that may allow for fetuses born at the cusp of viability (22-23 weeks) to gestate to term outside the mother’s body. Trialed with lamb fetuses at the equivalent of 22-24 human weeks of gestation, the technology, dubbed the “Biobag”, mimics the conditions of a fetus in utero, surrounding it with artificial amniotic fluid. If the Biobag is successful, almost half of a fetus’s gestation might be able to occur outside the womb. In August, scientists in Australia replicated the experiment, with the unnerving addition of dubbing the technology “ex-vivo uterine environment,” or EVE.

The crux of Firestone’s utopia is the idea of gender becoming essentially irrelevant for building families. Since the Supreme Court heard Obergefell and granted same-sex couples the right to marry, equal acknowledgement of gay and lesbian couples as legal paThe crux of Firestone’s utopia is the idea of gender as essentially irrelevant for building familiesents should follow.

More here.

Saturday Poem

Ormesby Psalter

East Anglican School, c. 1310

The psalter invites us to consider

a cat and a rat in relationship

to an arched hole, which we

shall call Circumstance. Out of

Circumstance walks the splendid

rat, who is larger than he ought

to be, and who affects an expression

of dapper cheer. We shall call him

Privilege. Apparently Privilege has

not noticed the cat, who crouches

a mere six inches from Circumstance,

and who will undoubtedly pin

Privilege’s back with one swift

swipe, a torture we can all nod at.

The cat, however, has averted

its gaze upward, possibly to heaven.

Perhaps it is thanking the Almighty

for the miraculous provision of a rat

just when Privilege becomes crucial

for sustenance or sport. The cat

we shall call Myself. Is it not

too bad that the psalter artist

abandoned Myself in this attitude

of prayerful expectation? We all

would have enjoyed seeing clumps of

Privilege strewn about Circumstance,

Myself curled in sleepy ennui,

or cleaning a practical paw.

by Rhoda Janzen

from Poetry Magazine, 2007

Friday, June 29, 2018

The phrase ‘necessary and sufficient’ blamed for flawed neuroscience

Editorial in Nature:

In his 1946 classic essay ‘Politics and the English language’, George Orwell argued that “if thought corrupts language, language can also corrupt thought”. Can the same be said for science — that the misuse and misapplication of language could corrupt research? Two neuroscientists believe that it can. In an intriguing paper published in the Journal of Neurogenetics, the duo claims that muddled phrasing in biology leads to muddled thought and, worse, flawed conclusions.

In his 1946 classic essay ‘Politics and the English language’, George Orwell argued that “if thought corrupts language, language can also corrupt thought”. Can the same be said for science — that the misuse and misapplication of language could corrupt research? Two neuroscientists believe that it can. In an intriguing paper published in the Journal of Neurogenetics, the duo claims that muddled phrasing in biology leads to muddled thought and, worse, flawed conclusions.

The phrase in the crosshairs is “necessary and sufficient”. It’s a popular one: figures suggest the wording pops up in some 3,500 scientific papers each year across genetics, cell biology and neuroscience alone. It’s not a new fad: Nature’s archives show consistent use since the nineteenth century.

Used properly, the phrase indicates a specific relationship between two events. For example, the statement, “I’ll pay for lunch if, and only if, you pay for breakfast,” can be written as, “You paying for breakfast is necessary and sufficient for me paying for lunch.”

But, argue Motojiro Yoshihara and Motoyuki Yoshihara, use of the phrase in research reports is problematic, and should be curtailed.

More here.

Thirty years later, what needs to change in our approach to climate change

James Hansen in the Boston Globe:

THIRTY YEARS AGO, while the Midwest withered in massive drought and East Coast temperatures exceeded 100 degrees Fahrenheit, I testified to the Senate as a senior NASA scientist about climate change. I said that ongoing global warming was outside the range of natural variability and it could be attributed, with high confidence, to human activity — mainly from the spewing of carbon dioxide and other heat-trapping gases into the atmosphere. “It’s time to stop waffling so much and say that the evidence is pretty strong that the greenhouse effect is here,” I said.

THIRTY YEARS AGO, while the Midwest withered in massive drought and East Coast temperatures exceeded 100 degrees Fahrenheit, I testified to the Senate as a senior NASA scientist about climate change. I said that ongoing global warming was outside the range of natural variability and it could be attributed, with high confidence, to human activity — mainly from the spewing of carbon dioxide and other heat-trapping gases into the atmosphere. “It’s time to stop waffling so much and say that the evidence is pretty strong that the greenhouse effect is here,” I said.

This clear and strong message about the dangers of carbon emissions was heard. The next day, it led the front pages of newspapers across the country. Climate theory led to political action with remarkable speed. Within four years, almost all nations, including the United States, signed a Framework Convention in Rio de Janeiro, agreeing that the world must avoid dangerous human-made interference with climate.

Sadly, the principal follow-ups to Rio were the precatory Kyoto Protocol and Paris Agreement — wishful thinking, hoping that countries will make plans to reduce emissions and carry them out. In reality, most countries follow their self-interest, and global carbon emissions continue to climb.

More here.

New research by Daniel Gilbert speaks to our conflicted relationship with progress

Peter Reuell in the Harvard Gazette:

By several measures, including rates of poverty and violence, progress is an international reality. Why, then, do so many of us believe otherwise?

By several measures, including rates of poverty and violence, progress is an international reality. Why, then, do so many of us believe otherwise?

The answer, Harvard researcher Daniel Gilbert says, may lie in “prevalence-induced concept change.”

In a series of studies, Gilbert, the Edgar Pierce Professor of Psychology, his postdoctoral student David Levari, and several other researchers show that as the prevalence of a problem is reduced, humans are inclined to redefine the problem. As a problem becomes smaller, conceptualizations of the problem expand, which can lead to progress being discounted. The research is described in a paper in the June 29 issue of Science.

“Our studies show that people judge each new instance of a concept in the context of the previous instances,” Gilbert said. “So as we reduce the prevalence of a problem, such as discrimination, for example, we judge each new behavior in the improved context that we have created.”

“Another way to say this is that solving problems causes us to expand our definitions of them,” he said. “When problems become rare, we count more things as problems. Our studies suggest that when the world gets better, we become harsher critics of it, and this can cause us to mistakenly conclude that it hasn’t actually gotten better at all. Progress, it seems, tends to mask itself.”

More here.

The New Faces Of The Democratic Party

Singing Against the Grain

Kira Thurman at The Point:

If the names of these Black Oberlinites are unfamiliar, I suspect it is with good reason: we do not know how to talk about them. Over the course of my life I have learned that to be black and a classical musician is to be considered a contradiction. After hearing that I was a music major, a TSA agent asked me if I was studying jazz. One summer in Bayreuth, a white German businessman asked me what I was doing in his town. Upon hearing that I was researching the history of Wagner’s opera house, he remarked, “But you look like you’re from Africa.” After I gushed about Mahler’s Fifth Symphony, someone once told me that I wasn’t “really black.” All too often, black artistic activities can only be recognized in “black” arts.

If the names of these Black Oberlinites are unfamiliar, I suspect it is with good reason: we do not know how to talk about them. Over the course of my life I have learned that to be black and a classical musician is to be considered a contradiction. After hearing that I was a music major, a TSA agent asked me if I was studying jazz. One summer in Bayreuth, a white German businessman asked me what I was doing in his town. Upon hearing that I was researching the history of Wagner’s opera house, he remarked, “But you look like you’re from Africa.” After I gushed about Mahler’s Fifth Symphony, someone once told me that I wasn’t “really black.” All too often, black artistic activities can only be recognized in “black” arts.

One reason it is difficult to talk about black classical musicians is because people assume they are elitist, as though to love Haydn piano sonatas—as I do—is somehow to betray black cultures in favor of a white, Western world. I have heard this particular indictment since my freshman year of college, and it hurts because it’s not too far off.

more here.

The Philosophy of Rom Com

Eric Thurm at Literary Hub:

Last week, the philosopher Stanley Cavell died. His contributions to human thought are vast and rich; his subjects range from the intricacies of human language to the nature of skill. But one of Cavell’s best-known books is also, at least at first glance, his most frivolous: Pursuits of Happiness. In this book, originally published in 1981, Cavell claims that what he calls “comedies of remarriage”—Hollywood comedies from the 1930s and 40s that share a set of genre conventions (borderline farcical cons, absent mothers, weaponized erotic dialogue), actors (Cary Grant, Clark Gable, Katharine Hepburn, Barbara Stanwyck), and settings (Connecticut)—are the inheritors of the tradition of Shakespearean comedy and romance, and that they constitute a philosophically significant body of work.

Last week, the philosopher Stanley Cavell died. His contributions to human thought are vast and rich; his subjects range from the intricacies of human language to the nature of skill. But one of Cavell’s best-known books is also, at least at first glance, his most frivolous: Pursuits of Happiness. In this book, originally published in 1981, Cavell claims that what he calls “comedies of remarriage”—Hollywood comedies from the 1930s and 40s that share a set of genre conventions (borderline farcical cons, absent mothers, weaponized erotic dialogue), actors (Cary Grant, Clark Gable, Katharine Hepburn, Barbara Stanwyck), and settings (Connecticut)—are the inheritors of the tradition of Shakespearean comedy and romance, and that they constitute a philosophically significant body of work.

What is there to learn from It Happened One Night, His Girl Friday, or The Lady Eve? In Cavell’s telling, almost everything. He describes the central theme of the genre as “the creation of the woman with and by means of a man.” If that sounds a bit retrograde—well, it is, a bit. But the “creation of the human,” as Cavell articulates it, is not as heavily gendered as it sounds; or at least, it doesn’t need to be.

more here.