Daniel Brook at The Nation:

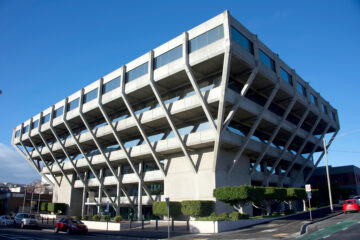

To enter the Rudolph retrospective at the Met is to be seduced. Enveloped in the museum’s 20th-century art galleries, the clean lines and daring spirit of Rudolph’s drawings place him comfortably in the company of the modern masters nearby. His geometric precision and imaginative forms echo Russian Constructivists like El Lissitzky. Exhibition photographs of Rudolph’s built works alluringly capture the interplay between light and shadow that animate the interiors and exteriors of his massive concrete structures. One featured building is a levitating layer cake improbably balanced on fluted columns; in another mock-up, a concrete snake of triangular apartment buildings slithers its way across Manhattan.

To enter the Rudolph retrospective at the Met is to be seduced. Enveloped in the museum’s 20th-century art galleries, the clean lines and daring spirit of Rudolph’s drawings place him comfortably in the company of the modern masters nearby. His geometric precision and imaginative forms echo Russian Constructivists like El Lissitzky. Exhibition photographs of Rudolph’s built works alluringly capture the interplay between light and shadow that animate the interiors and exteriors of his massive concrete structures. One featured building is a levitating layer cake improbably balanced on fluted columns; in another mock-up, a concrete snake of triangular apartment buildings slithers its way across Manhattan.

But Brutalism’s move from form to function is a journey from utopia to dystopia—a trajectory the curators pointedly ignore. Those photogenic fluted columns are from a parking garage that Rudolph jammed into the once-walkable heart of New Haven. A 1963 Vogue magazine feature, included in the galleries, shows Rudolph, dressed in a snappy suit, standing next to his gas guzzler on the parking garage’s roof.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

It is safe to say that perceptions of migrants are contradictory. In their countries of origin, they are sometimes celebrated for having embarked on adventures and sometimes criticized as having abandoned their homes. In the countries of their arrival, they can appear as terrifying threats in another people’s history or be welcomed as fresh blood. If they face hostility and suspicion, migrants might feel the need to insert themselves into their new nation’s chronicles of conquest. The migrant’s heroism can then harmonize with their host nation’s self-image, as well as affirming that nation’s hospitality and generosity.

It is safe to say that perceptions of migrants are contradictory. In their countries of origin, they are sometimes celebrated for having embarked on adventures and sometimes criticized as having abandoned their homes. In the countries of their arrival, they can appear as terrifying threats in another people’s history or be welcomed as fresh blood. If they face hostility and suspicion, migrants might feel the need to insert themselves into their new nation’s chronicles of conquest. The migrant’s heroism can then harmonize with their host nation’s self-image, as well as affirming that nation’s hospitality and generosity. They who in folly or mere greed

They who in folly or mere greed Washington DC. Boston, Massachusetts. Denver, Colorado. Seattle, Washington. Trenton, New Jersey

Washington DC. Boston, Massachusetts. Denver, Colorado. Seattle, Washington. Trenton, New Jersey E

E

Some of the microbes that rose from the ocean fell on land instead of water. Lying on the bare continents, they no longer had sea water to shield them from direct sunlight. Many likely died as the ultraviolet radiation ravaged their genes and proteins. Meanwhile, the atmosphere was sucking out the water from their interiors, causing their molecules to stick together and collapse into toxic shapes.

Some of the microbes that rose from the ocean fell on land instead of water. Lying on the bare continents, they no longer had sea water to shield them from direct sunlight. Many likely died as the ultraviolet radiation ravaged their genes and proteins. Meanwhile, the atmosphere was sucking out the water from their interiors, causing their molecules to stick together and collapse into toxic shapes.

In his introduction, Clark poses a more immediate question: “Shouldn’t we judge political art by its effects, not its beauty or truth?” Leaving aside the second clause, we find two questionable assertions implicit in the first: namely, that art can be political and that it can have an effect. In this context, he imagines the reader wondering why his book “makes room for Matisse and Jackson Pollock,” two artists who “reached the conclusion, in practice, that opinions had to be what art annihilated if it was to survive”. Their stance is one that Clark accepts: “The blankness was essential. It was reality as they lived it.”

In his introduction, Clark poses a more immediate question: “Shouldn’t we judge political art by its effects, not its beauty or truth?” Leaving aside the second clause, we find two questionable assertions implicit in the first: namely, that art can be political and that it can have an effect. In this context, he imagines the reader wondering why his book “makes room for Matisse and Jackson Pollock,” two artists who “reached the conclusion, in practice, that opinions had to be what art annihilated if it was to survive”. Their stance is one that Clark accepts: “The blankness was essential. It was reality as they lived it.”