Dean Kissick in Harper’s Magazine:

My mother lost both of her legs on the way to the Barbican Art Gallery. It was her day off, and she was going there to see an exhibition called Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art. She had just arrived in London on a coach from Oxford and was run over by a bus outside Victoria Station. This was on a Friday morning in early May. The next day, in my apartment in Manhattan, I received an unexpected call—my mother never calls me—from a trauma ward in West London. “I’m in a lot of pain,” she said in a loud, anguished, slurring voice I hardly recognized, “but I’m in very good hands.” A few hours later, I was on a flight home.

My mother lost both of her legs on the way to the Barbican Art Gallery. It was her day off, and she was going there to see an exhibition called Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art. She had just arrived in London on a coach from Oxford and was run over by a bus outside Victoria Station. This was on a Friday morning in early May. The next day, in my apartment in Manhattan, I received an unexpected call—my mother never calls me—from a trauma ward in West London. “I’m in a lot of pain,” she said in a loud, anguished, slurring voice I hardly recognized, “but I’m in very good hands.” A few hours later, I was on a flight home.

When I visited her in the hospital, Mom asked me whether the show was worth losing her legs for. “No,” I told her, though at that point, I hadn’t seen it. When I did, two weeks later, my answer proved correct. Unravel featured tapestries, quilts, needlework, sculptures, and installations by modern artists, the majority of whom were of historically marginalized identities. The curators proposed that textiles themselves had also been marginalized, having been gendered as feminine and regarded as “craft” rather than “fine art.” As a result, the exhibition’s introductory text argued, the more politically radical aspects of textile making had been obscured. “What does it mean to imagine a needle, a loom or a garment as a tool of resistance?” the text asked.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

For those hoping to cure death, and they are legion, a 2016 experiment at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in San Diego has become liminal — the moment that changed everything. The experiment involved mice born to live fast and die young, bred with a rodent version of progeria, a condition that causes premature aging. Left alone, the animals grow gray and frail and then die about seven months later, compared to a lifespan of about two years for typical lab mice.

For those hoping to cure death, and they are legion, a 2016 experiment at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in San Diego has become liminal — the moment that changed everything. The experiment involved mice born to live fast and die young, bred with a rodent version of progeria, a condition that causes premature aging. Left alone, the animals grow gray and frail and then die about seven months later, compared to a lifespan of about two years for typical lab mice. The Great Gatsby

The Great Gatsby It’s no secret that modern English is saturated with French. Insults and derogatory terms owe much to the French example – bastard, brute, coward, rascal, idiot. French oozes from the language of food and drink: chowder echoes the old French chaudière, meaning a cooking pot, while crayfish started out as escrevise before the English chopped off its initial vowel (something they also did with scarf, stew, slice and a host of others) and decided that the last syllable sounding like ‘fish’ was just too good to pass up. From arson to evidence, jury to slander, French runs through the language of the English law (and the ‘Oyez! Oyez! Oyez!’ of the

It’s no secret that modern English is saturated with French. Insults and derogatory terms owe much to the French example – bastard, brute, coward, rascal, idiot. French oozes from the language of food and drink: chowder echoes the old French chaudière, meaning a cooking pot, while crayfish started out as escrevise before the English chopped off its initial vowel (something they also did with scarf, stew, slice and a host of others) and decided that the last syllable sounding like ‘fish’ was just too good to pass up. From arson to evidence, jury to slander, French runs through the language of the English law (and the ‘Oyez! Oyez! Oyez!’ of the  I avoid contact with fans. Occasionally, I watch trash TV because I think the poet shouldn’t avert his eyes. I want to know what others aspire to. I’m a good but limited cook. My steaks are excellent, but they’ll never touch what you can get on any street corner in Argentina. Tree huggers are suspicious to me. Yoga classes for five-year-olds—which in California are a thing—are suspicious to me. I don’t use social media. If you see my profile anywhere there, you can be sure it’s a fake. I don’t use a smartphone. I never quite trust the media, so I get a truer picture of the political situation by going to multiple sources—the Western media, Al Jazeera, Russian TV, and occasionally by downloading the whole of a politician’s speech. I trust the Oxford English Dictionary, which is one of mankind’s greatest cultural achievements. I mean the one in twenty massive volumes with six hundred thousand entries and more than three million quotations culled from all over the English-speaking world and over a thousand years. I reckon thousands of researchers and amateur helpers spent 150 years combing through everything recorded. For me, it is the book of books, the one I would take to a desert island. It is inexhaustible, a miracle. The first time I visited Oliver Sacks on Wards Island north of Manhattan, I had mislaid the house number but knew the name of the little street. It was evening, winter-time; the slightly sloping street was icy. I parked and tiptoed along the icy pavement looking into every lit-up home. None of the windows had curtains. Through one window I saw a man sprawled on a sofa with one of the hefty volumes of the OED propped on his chest. I knew that had to be him, and so it was. Our first subject was the dictionary; for him as well, it was the book of books.

I avoid contact with fans. Occasionally, I watch trash TV because I think the poet shouldn’t avert his eyes. I want to know what others aspire to. I’m a good but limited cook. My steaks are excellent, but they’ll never touch what you can get on any street corner in Argentina. Tree huggers are suspicious to me. Yoga classes for five-year-olds—which in California are a thing—are suspicious to me. I don’t use social media. If you see my profile anywhere there, you can be sure it’s a fake. I don’t use a smartphone. I never quite trust the media, so I get a truer picture of the political situation by going to multiple sources—the Western media, Al Jazeera, Russian TV, and occasionally by downloading the whole of a politician’s speech. I trust the Oxford English Dictionary, which is one of mankind’s greatest cultural achievements. I mean the one in twenty massive volumes with six hundred thousand entries and more than three million quotations culled from all over the English-speaking world and over a thousand years. I reckon thousands of researchers and amateur helpers spent 150 years combing through everything recorded. For me, it is the book of books, the one I would take to a desert island. It is inexhaustible, a miracle. The first time I visited Oliver Sacks on Wards Island north of Manhattan, I had mislaid the house number but knew the name of the little street. It was evening, winter-time; the slightly sloping street was icy. I parked and tiptoed along the icy pavement looking into every lit-up home. None of the windows had curtains. Through one window I saw a man sprawled on a sofa with one of the hefty volumes of the OED propped on his chest. I knew that had to be him, and so it was. Our first subject was the dictionary; for him as well, it was the book of books. On Saturday Francis Collins resigned from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) after directing it for over a decade. His departure, coming on the heels of the expected confirmation of Stanford’s Jay Bhattacharya as his replacement, represents more than the loss of an influential physician-scientist who once

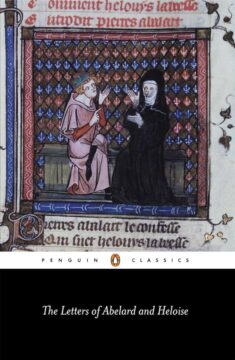

On Saturday Francis Collins resigned from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) after directing it for over a decade. His departure, coming on the heels of the expected confirmation of Stanford’s Jay Bhattacharya as his replacement, represents more than the loss of an influential physician-scientist who once  Whenever I read The Letters of Abelard and Héloïse I have in mind another, more contemporary couple, whose collaborative work I have come to think of as sacred, too. As soon as the performance artists Marina Abramović and Ulay met in the 1970s, they fell hard in love and began making performance art together. They called this work a “third energy,” their souls combined, a kind of artistic procreation (we don’t know what happened to Héloïse and Abelard’s child—only that she called him Astrolabe, after the astronomical instrument for reckoning with time and observing the stars. Astrolabe as the one instrument that could point up to the star-crossed lovers who made him and prove that their love had been real). The idea for “The Lovers” came to Abramović as a vision in a dream. They would walk from either end of the Great Wall of China to finally meet in the middle where they would marry, documenting the whole expedition on film—the kind of exaggeratedly cinematic, romantic scheme that is destined to go wrong. In the time it took to secure their visas—several years—the relationship had already begun to fall apart. Five years later, they set out at last to make “The Lovers.” After almost 90 days of walking, each covering over two thousand kilometres alone, they reunited on the wall, not to marry, but to break up. Watching the footage of “The Lovers,” I imagine they are actually Héloïse and Abelard, setting out on their private pilgrimages through life in the wake of their painful estrangement, then meeting in the middle again through the form of letters.

Whenever I read The Letters of Abelard and Héloïse I have in mind another, more contemporary couple, whose collaborative work I have come to think of as sacred, too. As soon as the performance artists Marina Abramović and Ulay met in the 1970s, they fell hard in love and began making performance art together. They called this work a “third energy,” their souls combined, a kind of artistic procreation (we don’t know what happened to Héloïse and Abelard’s child—only that she called him Astrolabe, after the astronomical instrument for reckoning with time and observing the stars. Astrolabe as the one instrument that could point up to the star-crossed lovers who made him and prove that their love had been real). The idea for “The Lovers” came to Abramović as a vision in a dream. They would walk from either end of the Great Wall of China to finally meet in the middle where they would marry, documenting the whole expedition on film—the kind of exaggeratedly cinematic, romantic scheme that is destined to go wrong. In the time it took to secure their visas—several years—the relationship had already begun to fall apart. Five years later, they set out at last to make “The Lovers.” After almost 90 days of walking, each covering over two thousand kilometres alone, they reunited on the wall, not to marry, but to break up. Watching the footage of “The Lovers,” I imagine they are actually Héloïse and Abelard, setting out on their private pilgrimages through life in the wake of their painful estrangement, then meeting in the middle again through the form of letters. To understand Trump’s political order, then, we need to familiarize ourselves with the

To understand Trump’s political order, then, we need to familiarize ourselves with the M

M D

D Building a film around a temperamental genius is never as simple as placing a star at its center. Murphy and Chalamet both do their parts: they create, they scowl, they have affairs. They are misunderstood. But their perceived genius is less about their particular actions than it is about the reactions of secondary characters. This is apparent throughout A Complete Unknown. In her review of the film, Vulture’s Alison Willmore highlights the cast around Chalamet: “Its best sequences aren’t about Dylan so much as they are about what it was like to be in his orbit when it felt like he could remake the universe.” The film succeeds because it captures how Dylan’s peers saw him—what made them want to be near him, what made them want to support his career.

Building a film around a temperamental genius is never as simple as placing a star at its center. Murphy and Chalamet both do their parts: they create, they scowl, they have affairs. They are misunderstood. But their perceived genius is less about their particular actions than it is about the reactions of secondary characters. This is apparent throughout A Complete Unknown. In her review of the film, Vulture’s Alison Willmore highlights the cast around Chalamet: “Its best sequences aren’t about Dylan so much as they are about what it was like to be in his orbit when it felt like he could remake the universe.” The film succeeds because it captures how Dylan’s peers saw him—what made them want to be near him, what made them want to support his career. In Kinsky’s latest novel,

In Kinsky’s latest novel,  I can’t recall the first time I saw “The Misfits,” John Huston’s 1961 cinematic masterpiece about a quartet of mutually disenfranchised wanderers, but I’m certain it was after I’d become a divorcée. I know it wouldn’t have stuck with me so permanently otherwise. Set in Reno, Nev., a city once as famous for its hassle-free divorces as its casinos, the film is a timeless meditation on what it means to lose.

I can’t recall the first time I saw “The Misfits,” John Huston’s 1961 cinematic masterpiece about a quartet of mutually disenfranchised wanderers, but I’m certain it was after I’d become a divorcée. I know it wouldn’t have stuck with me so permanently otherwise. Set in Reno, Nev., a city once as famous for its hassle-free divorces as its casinos, the film is a timeless meditation on what it means to lose. Working in the field of genetics is a bizarre experience. No one seems to be interested in the most interesting applications of their research.

Working in the field of genetics is a bizarre experience. No one seems to be interested in the most interesting applications of their research. The 20th century had a bunch of rising powers that all reached their peaks in terms not just of relative military might and economic strength, but of technological and cultural innovation. These included the United States, Japan, Germany, and Russia. So far, the 21st century is a little different, because only one major civilization is

The 20th century had a bunch of rising powers that all reached their peaks in terms not just of relative military might and economic strength, but of technological and cultural innovation. These included the United States, Japan, Germany, and Russia. So far, the 21st century is a little different, because only one major civilization is