Category: Recommended Reading

“Liberals Have Compromised on Their Own Values”: An Interview with Ali A. Rizvi

Maarten Boudry in Quillette:

The Pakistani-Canadian writer Ali Rizvi is a fierce critic of Islam, the religion in which he grew up. But unlike many other critics who maintain that Islam is inherently incapable of modernization, and that the Muslim world is sliding ever further into backwardness and fundamentalism, Rizvi is refreshingly optimistic about the future. The seed of a new Enlightenment has been planted in the Arabic world, he told me in Antwerp, and there’s no way to eradicate it.

In his book The Atheist Muslim, Rizvi speaks directly to the many closeted atheists, agnostics, and secularists in the Muslim world. These people are obliged by the societies in which they live to present themselves outwardly as Muslims, but in private, they harbor different ideas. Rizvi’s book is often polemical in tone, but also humane and sympathetic to the plight of Muslims around the world. He is keenly aware of the consolations which faith provide to some, and he never stoops to condescension.

If Rizvi is right, freethinkers in the Muslim world are more numerous than most of us suspect. Not only are their numbers growing, but they are becoming more and more emboldened. With eloquent and outspoken ex-Muslims such as Rizvi, who offer a message of hope and liberation from dogma, religious conservatives around the world should start to worry.

More here.

Thursday Poem

School of the Americas

Sergio has ink-pot eyes, girlish wrists.

He draws superheroes extremely well—

Avengers, Wolfman, El Toro Rojo,

any one wearing a mask. Monday nights

we drive to the art club meeting

in the cream-colored Sunbird

I bought with babysitting money.

I don’t know how he ended up with his mom

in the South, just the two of them, but

I spend 9th grade sitting next to him,

translating a Georgia O’Keefe painting

into pastel chalk: a lily dusted with pollen.

One day during class, Sergio tells me he saw

his grandparents shot before his eyes

back in Colombia. The phrase sticks out

in his heavy accent, like a child repeating

something just overheard. After a few minutes,

we go back to our drawings.

In the evenings that year I sign my name

to stock letters sent by Amnesty International

and mail them to faraway dictators

of the 1990s: Mubarak, Mobutu, Marcos.

All the while a quarter of a tank away,

at the School of the Americas (now the

Western Hemispheres Institute for Security

Cooperation) hundreds of Colombian

soldiers train in truth extraction,

how to intimidate, the best ways

to torture. In the yearbook,

I list my hobbies: poetry

and human rights. I have yet

to draw a picture of anything

from life—the art teacher seems

disappointed that Sergio and I

are mere copyists. After graduation,

Sergio finished a year

of art school in Chicago,

got cancer and died.

I guess I had a crush on him

when we were fourteen,

and I sat next to him,

copying those sexual flowers.

One has to start somewhere.

Just start: before my eyes could see,

I drew things like that lily.

.

by Rebecca Black

from Split This Rock, 2014

Ants Among Elephants – life as an ‘untouchable’ in modern India

Amit Chaudhuri in The Guardian:

Not long ago, at a conference that brought together academics, writers and artists in Kochi in south India, the historian Vivek Dhareshwar unsettled his audience by saying that there was no such thing as caste – that it was a conceptual category the British used to understand and reduce India, which was internalised almost at once by Indians. “Caste” was not a translation of “jaati”, said Dhareshwar; “jaati” was a translation of “caste” – that is, the internalisation by Indians of the assumptions that the word caste involve meant they took its timelessness and authenticity for granted. Dhareshwar seemed to be implying – forcefully and outlandishly – that caste was at once a colonial inheritance and a habit of thinking, whose provenance no one felt the need to inquire into any longer. This was deeply nervous-making. For one thing, no doubt the predominantly upper-caste right – rigorously free-market Brahminical in tone even if not always in caste origin – would love such an argument as further support for its article of faith: that Hinduism is a wonderful religion, and any blemish it might have has been caused by outsiders or by colonial interference. It does seem a bit tendentious to attribute such inventive conceptual powers wholesale to the British. If Indians subscribe to invented versions of their culture, they must take responsibility and credit for having created a very large number themselves.

Not long ago, at a conference that brought together academics, writers and artists in Kochi in south India, the historian Vivek Dhareshwar unsettled his audience by saying that there was no such thing as caste – that it was a conceptual category the British used to understand and reduce India, which was internalised almost at once by Indians. “Caste” was not a translation of “jaati”, said Dhareshwar; “jaati” was a translation of “caste” – that is, the internalisation by Indians of the assumptions that the word caste involve meant they took its timelessness and authenticity for granted. Dhareshwar seemed to be implying – forcefully and outlandishly – that caste was at once a colonial inheritance and a habit of thinking, whose provenance no one felt the need to inquire into any longer. This was deeply nervous-making. For one thing, no doubt the predominantly upper-caste right – rigorously free-market Brahminical in tone even if not always in caste origin – would love such an argument as further support for its article of faith: that Hinduism is a wonderful religion, and any blemish it might have has been caused by outsiders or by colonial interference. It does seem a bit tendentious to attribute such inventive conceptual powers wholesale to the British. If Indians subscribe to invented versions of their culture, they must take responsibility and credit for having created a very large number themselves.

Caste has been the author of such violence in India – people were dying of caste-based violence even as we sat and listened to Dhareshwar in that hotel – that to deny its existence would have seemed like denying the Holocaust. This violence continues despite the fact that “untouchables, backward and scheduled castes, and scheduled tribes” form the majority of India’s population.

White threat in a browning America

Ezra Klein in Vox:

In 2008, Barack Obama held up change as a beacon, attaching to it another word, a word that channeled everything his young and diverse coalition saw in his rise and their newfound political power: hope. An America that would elect a black man president was an America in which a future was being written that would read thrillingly different from our past. In 2016, Donald Trump wielded that same sense of change as a threat; he was the revanchist voice of those who yearned to make America the way it was before, to make it great again. That was the impulse that connected the wall to keep Mexicans out, the ban to keep Muslims away, the birtherism meant to prove Obama couldn’t possibly be a legitimate president. An America that would elect Donald Trump president was an America in which a future was being written that could read thrillingly similar to our past. This is the core cleavage of our politics, and it reflects the fundamental reality of our era: America is changing, and fast. According to the Census Bureau, 2013 marked the first yearthat a majority of US infants under the age of 1 were nonwhite. The announcement, made during the second term of the nation’s first African-American president, was not a surprise. Demographers had been predicting such a tipping point for years, and they foresaw more to come.

In 2008, Barack Obama held up change as a beacon, attaching to it another word, a word that channeled everything his young and diverse coalition saw in his rise and their newfound political power: hope. An America that would elect a black man president was an America in which a future was being written that would read thrillingly different from our past. In 2016, Donald Trump wielded that same sense of change as a threat; he was the revanchist voice of those who yearned to make America the way it was before, to make it great again. That was the impulse that connected the wall to keep Mexicans out, the ban to keep Muslims away, the birtherism meant to prove Obama couldn’t possibly be a legitimate president. An America that would elect Donald Trump president was an America in which a future was being written that could read thrillingly similar to our past. This is the core cleavage of our politics, and it reflects the fundamental reality of our era: America is changing, and fast. According to the Census Bureau, 2013 marked the first yearthat a majority of US infants under the age of 1 were nonwhite. The announcement, made during the second term of the nation’s first African-American president, was not a surprise. Demographers had been predicting such a tipping point for years, and they foresaw more to come.

White voters who feel they are losing a historical hold on power are reacting to something real. For the bulk of American history, you couldn’t win the presidency without winning a majority — usually an overwhelming majority — of the white vote. Though this changed before Obama (Bill Clinton won slightly less of the white vote than his Republican challengers), the election of an African-American president leading a young, multiracial coalition made the transition stark and threatening. This is the crucial context for Trump’s rise, and it’s why Tesler has little patience for those who treat Trump as an invader in the Republican Party. In a field of Republicans who were trying to change the party to appeal to a rising Hispanic electorate, Trump was alone in speaking to Republican voters who didn’t want the party to remake itself, who wanted to be told that a wall could be built and things could go back to the way they were. “Trump met the party where it was rather than trying to change it,“ Tesler says. “He was hunting where the ducks were.”

More here. (Note: Thanks to Jehanzeb Kayani)

Wednesday, August 1, 2018

Alfred Döblin’s Berlin

Adam Kirsch in The Nation:

Adam Kirsch in The Nation:

What is Alexanderplatz in Berlin?” asked Walter Benjamin in his review of Alfred Döblin’s Berlin Alexanderplatz. As Döblin’s original readers would have known quite well, Alexanderplatz is a square in central Berlin that serves as a transportation hub and as the anchor of a commercial district. But for Benjamin, the key fact about Alexanderplatz in 1929, when Döblin’s book was published, was that it was a vast construction site, “where for the last two years the most violent transformations have been taking place, where excavators and jackhammers have been continuously at work, where the ground trembles under the impact of their blows.”

Alexanderplatz, then, was the scene of a modern metropolis coming dangerously and discordantly into being—just as Berlin does in Döblin’s novel. In his afterword, Michael Hofmann, who gives us an impressively wild and fearless new translation of the book, credits it with founding “the idea of modern city literature altogether.” This might be an exaggeration of its uniqueness: Any English-speaking reader will immediately think of James Joyce and John Dos Passos as parallels, if not necessarily precursors. Like them, Döblin makes use of stream of consciousness, collage and montage, the collision of discourses and registers. One might also think of T.S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land,” with its hypnotic vision of London as an “Unreal City” and the crowds of the living dead flowing over London Bridge. But when the city in question is Weimar-era Berlin, the urban chaos and dread take on new dimensions. In Berlin Alexanderplatz, we are plunged into a cauldron of alienation, violence, and social breakdown that would, just a few years after Döblin wrote his novel, deliver all of Germany into the hands of the Nazis.

More here.

Jeff Bezos’s $150 Billion Fortune Is a Policy Failure

Annie Lowrey in The Atlantic:

Last month, Bloomberg reported that Jeff Bezos, the founder of Amazon and owner of the Washington Post, has accumulated a fortune worth $150 billion. That is the biggest nominal amount in modern history, and extraordinary any way you slice it. Bezos is the world’s lone hectobillionaire. He is worth what the average American family is, nearly two million times over. He has about 50 percent more money than Bill Gates, twice as much as Mark Zuckerberg, 50 times as much as Oprah, and perhaps 100 times as much as President Trump. (Who knows!) He has gotten $50 billion richer in less than a year. He needs to spend roughly $28 million a day just to keep from accumulating more wealth.

This is a credit to Bezos’s ingenuity and his business acumen. Amazon is a marvel that has changed everything from how we read, to how we shop, to how we structure our neighborhoods, to how our postal system works. But his fortune is also a policy failure, an indictment of a tax and transfer system and a business and regulatory environment designed to supercharging the earnings of and encouraging wealth accumulation among the few. Bezos did not just make his $150 billion. In some ways, we gave it to him, perhaps to the detriment of all of us.

More here.

Robert Wright on Why Buddhism is True

Over at Philosophy Bites:

Robert Wright argues that some aspects of Buddhism, particularly those parts that deal with the self and the mind, are both compatible with contemporary evolutionary theory and profound about our nature. In this episode of the Philosophy Bites podcast he discusses why he thinks Buddhism is essentially true with Nigel Warburton.

The Seducer

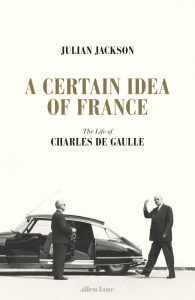

Ferdinand Mount in the LRB:

Ferdinand Mount in the LRB:

Philippe Pétain died at 9.22 a.m. on 23 July 1951. He had been tried for treason in 1945, while General de Gaulle was still in his first spell of power. The hero of Verdun was sentenced to death by one vote, but the court asked for the sentence to be commuted to life imprisonment in view of the marshal’s great age, which was a relief to de Gaulle. Since then Pétain had been banged up on the Ile d’Yeu, 11 miles off the Vendée coast. At the time of his death, he was 95 years old and wandering in his wits. Even so, ministers in Paris were anxious to see the back of him. By lunchtime two days later, he was being hustled underground at the Port-Joinville cemetery on the island. Passing on the news to de Gaulle, Georges Pompidou, his directeur de cabinet and a former Rothschild banker, remarked: ‘The affair is now over, once and for all.’ De Gaulle disagreed: ‘No, it was a great historical drama, and a historical drama is never over.’ What an extraordinary drama it was, the relationship between the two men, played out over nearly forty years, encapsulating the whole agony of France, and leaving behind resentments and divisions that are not quite dead even now.

More here.

Why Nothing Changes (Until it Does)

Nihilism in the 21st Century: A Conversation with Pankaj Mishra, Shruti Kapila and David Priestland

U.S WITHDRAWL FROM THE PARIS CLIMATE AGREEMENT

More here.

Wednesday Poem

for Willie Louis 1937-2013, who testified

against two men who killed Emmett Till,

1955, Money, Mississippi

When Your Word is a Match

When you walk past Klans-

men, smiling at you

on your way into the court

house, wondering how

you will ever live here

after this airless day.

When you tell the story

of a pick-up truck,

a barn, a boy, a threat.

When you point at two

men in the courtroom

and everyone gasps at

what they have never seen

before, but know is true.

When your word is a match-

head, hissing into flame,

testifying aloud but blown

out as soon as you speak.

When all the air

in the courtroom shakes

its white head.

When the smiling men brag

about killing the boy

in the barn. When they

joke about a river, about

what cannot float. When

you flee to the mother’s

city, to breathe air that isn’t

a gasp. When you hide

the name your parents gave

you for fear the men from

that barn will come

smiling for you too.

When you speak to your wife

years later, after a lifetime

of breathing beside her.

When this air thick as lead

presses your chest to breaking.

When the match’s flame

consumes all the air, revealing

a coffin, a boy, a mother,

and you, burning still.

by Joseph Ross

from Ache

Sibling Rivalry Press, 2017

How the evidence stacks up for preventing Alzheimer’s disease

Emily Sohn in Nature:

Alzheimer’s disease has long been considered an inevitable consequence of ageing that is exacerbated by a genetic predisposition. Increasingly, however, it is thought to be influenced by modifiable lifestyle behaviours that might enable a person’s risk of developing the condition to be controlled. But even as evidence to support this idea has accumulated over the past decade, the research community has been slow to adopt the idea. This reluctance was obvious as recently as 2010, when the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) brought together a panel of 15 researchers to consider the state of research on preventing Alzheimer’s disease, at a conference in Bethesda, Maryland. Tantalizing findings had begun to emerge that suggested that behavioural choices such as engaging in physical exercise, intellectual stimulation and healthy eating could reduce the risk of brain degeneration. In a 2006 study1 that followed more than 2,200 people in New York for four years, researchers found that people who adhered to a Mediterranean diet — full of whole grains, fruit and vegetables, fish and olive oil — had an up to 40% lower risk of dementia than people who ate more dairy products and meat.

Alzheimer’s disease has long been considered an inevitable consequence of ageing that is exacerbated by a genetic predisposition. Increasingly, however, it is thought to be influenced by modifiable lifestyle behaviours that might enable a person’s risk of developing the condition to be controlled. But even as evidence to support this idea has accumulated over the past decade, the research community has been slow to adopt the idea. This reluctance was obvious as recently as 2010, when the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) brought together a panel of 15 researchers to consider the state of research on preventing Alzheimer’s disease, at a conference in Bethesda, Maryland. Tantalizing findings had begun to emerge that suggested that behavioural choices such as engaging in physical exercise, intellectual stimulation and healthy eating could reduce the risk of brain degeneration. In a 2006 study1 that followed more than 2,200 people in New York for four years, researchers found that people who adhered to a Mediterranean diet — full of whole grains, fruit and vegetables, fish and olive oil — had an up to 40% lower risk of dementia than people who ate more dairy products and meat.

…In 2016, Isaacson’s team observed that after just six months on a personalized preventive plan, participants showed improvements in executive function and mental-processing speed17. The researchers will soon reveal results gathered from a group of more than 150 people at the New York clinic, and the early signs are encouraging. On the basis of this work, Isaacson suspects that 60% of lifestyle recommendations will be the same for everyone; eating a Mediterranean diet, for instance, seems to be a universally positive strategy. The rest should vary from person to person and could include interventions such as aggressive treatment for cardiovascular conditions, medication for sleep apnoea or participation in specific types of physical activity. “We can’t have a one-size-fits-all approach.

More here.

Tuesday, July 31, 2018

Amitava Kumar’s latest novel explores the intersection of the sexual and the political

Joanna Biggs in The New Yorker:

You look at a dark immigrant in that long line at JFK,” Kailash, the protagonist of Amitava Kumar’s new nonfiction novel, “Immigrant, Montana” (Knopf), says of his fellow New Yorkers. “You look at him and think that he wants your job and not that he just wants to get laid.” In 1990, Kailash arrives in New York City from the eastern-Indian city of Ara to study literature; sex for him has gone only as far as a fleeting topless shot at the movies before the censor’s cut. John Donne, in “To His Mistress Going to Bed,” imagined his lover’s body as his America, awaiting discovery; Kailash is hopeful that America the beautiful can be explored through its women’s bodies.

You look at a dark immigrant in that long line at JFK,” Kailash, the protagonist of Amitava Kumar’s new nonfiction novel, “Immigrant, Montana” (Knopf), says of his fellow New Yorkers. “You look at him and think that he wants your job and not that he just wants to get laid.” In 1990, Kailash arrives in New York City from the eastern-Indian city of Ara to study literature; sex for him has gone only as far as a fleeting topless shot at the movies before the censor’s cut. John Donne, in “To His Mistress Going to Bed,” imagined his lover’s body as his America, awaiting discovery; Kailash is hopeful that America the beautiful can be explored through its women’s bodies.

Getting laid has always been a way that outsiders have attempted to conquer (and to write about) the big city, from Tom Jones to Frédéric Moreau to Alexander Portnoy. Kumar himself arrived at Syracuse University in the late eighties from Delhi via Ara; he is now a professor at Vassar and has written six books of nonfiction, one of poetry, and a previous novel. The new book falls between genres. Its aim is not to tell a story, exactly, but to create a portrait of a mind moving uneasily between a new, chosen culture and the one left behind. Kailash’s journey toward sexual integration in the West is cast (to quote the author’s note) as “a work of fiction as well as nonfiction, an in-between novel by an in-between writer,” complete with multiple epigraphs, pictures, footnotes academic and digressive, and both pop-cultural and literary-theoretical references. So the form of “Immigrant, Montana” calls to mind works by Teju Cole (to whom the book is dedicated), Sheila Heti, and Ben Lerner. Can we believe in the immigrant who happens to write in the hippest, Brooklyniest form going? What sort of outsider knows the rules so preternaturally well?

More here.

Scientists, Stop Thinking Explaining Science Will Fix Things

Tim Requarth in Slate:

If you consider yourself to have even a passing familiarity with science, you likely find yourself in a state of disbelief as the president of the United States calls climate scientists “hoaxsters” and pushes conspiracy theories about vaccines. The Trump administration seems practically allergic to evidence. And it’s not just Trump—plenty of people across the political spectrum hold bizarre and inaccurate ideas about science, from climate change and vaccines to guns and genetically modified organisms.

If you consider yourself to have even a passing familiarity with science, you likely find yourself in a state of disbelief as the president of the United States calls climate scientists “hoaxsters” and pushes conspiracy theories about vaccines. The Trump administration seems practically allergic to evidence. And it’s not just Trump—plenty of people across the political spectrum hold bizarre and inaccurate ideas about science, from climate change and vaccines to guns and genetically modified organisms.

If you are a scientist, this disregard for evidence probably drives you crazy. So what do you do about it?

It seems many scientists would take matters into their own hands by learning how to better communicate their subject to the masses. I’ve taught science communication at Columbia University and New York University, and I’ve run an international network of workshops for scientists and writers for nearly a decade. I’ve always had a handful of intrepid graduate students, but now, fueled by the Trump administration’s Etch A Sketch relationship to facts, record numbers of scientists are setting aside the pipette for the pen. Across the country, science communication and advocacy groups report upticks in interest. Many scientists hope that by doing a better job of explaining science, they can move the needle toward scientific consensus on politically charged issues. As recent studies from Michigan State University found, scientists’ top reason for engaging the public is to inform and defend science from misinformation.

It’s an admirable goal, but almost certainly destined to fail.

More here.

Actually, Republicans Do Believe in Climate Change

Leaf Van Boven and David Sherman in the New York Times:

It is widely believed that most Republicans are skeptical about human-caused climate change. But is this belief correct?

It is widely believed that most Republicans are skeptical about human-caused climate change. But is this belief correct?

In 2014 and 2016, we conducted two national surveys of more than 2,000 respondents on the issue of climate change. We found that most Republicans agreed that climate change is happening, threatens humans and is caused by human activity — and that reducing carbon emissions would mitigate the problem.

To be sure, Democrats agreed more strongly than Republicans did that climate change is a concerning reality. And among climate skeptics there were more Republicans than Democrats. Nevertheless, most Republicans were in basic agreement with most Democrats and independents on this issue.

This raises a question: If Democrats and Republicans agree about climate change, why do they disagree about climate policy?

More here.

Boots Riley’s Dystopian Satire “Sorry to Bother You” Is an Anti-Capitalist Rallying Cry for Workers

How Science and Myth Collide in Water

Philip Ball at Lapham’s Quarterly:

Water attracts trouble. Time and again this ubiquitous and vital substance becomes the subject of controversial claims. The latest is about “raw” or “live” water, consumed directly from natural springs with no treatment or purification.

Water attracts trouble. Time and again this ubiquitous and vital substance becomes the subject of controversial claims. The latest is about “raw” or “live” water, consumed directly from natural springs with no treatment or purification.

It’s largely a Silicon Valley thing. About thirty dollars will buy you five gallons from the Oregon-based company Live Water.

Sure, raw water might be full of other stuff like bacteria, algae, and minerals. But these, say devotees, are good for us—unlike the antimicrobial agents and additives in tap water or the plastic additives leached into bottled water. Fluoride, added to tap water for dental health, has a particularly long history of health scares and conspiracy theories; in the 1950s some said fluoridation was a communist plot to undermine the health of Americans. Raw-water advocates contend that fluoride is neurotoxic even at very low levels, although there’s no evidence of that.

more here.

Various Films

A. S. Hamrah at n+1:

To that end, First Reformed is daring and unrelenting—it searches for and pinpoints real harm. Ten people walked out of the theater where I saw it, most of them Schrader’s age. I think they left because the film’s intensity was too much in a world where they had the option of seeing Book Club at a theater down the street.

To that end, First Reformed is daring and unrelenting—it searches for and pinpoints real harm. Ten people walked out of the theater where I saw it, most of them Schrader’s age. I think they left because the film’s intensity was too much in a world where they had the option of seeing Book Club at a theater down the street.

Most people at the screening were younger, and they stayed put for an ending that includes a glass of Drano and a barbed wire vest. As I’ve tried to convey, the film is bleak. But contrary to what we’re told, I don’t think audiences want upbeat films in bad times. Hollywood takes advantage of bad times by telling people that’s what they want, because that’s what they were going to make anyway.

more here.