Sophie Haigney in More Intelligent Life:

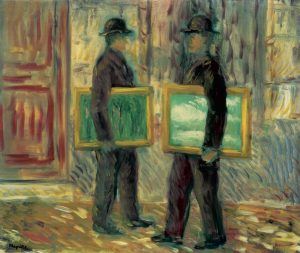

It is sometimes said that Surrealist paintings are disappointing up close; perhaps we see them so often in reproduction that by the time we see the real ones in a museum they’ve lost some of their strangeness. René Magritte’s paintings could fall into that trap. His bowler hats, apples, puffy clouds and pipes have popped up on coffee mugs, tote bags and dorm-room posters for decades. Not to mention album covers: Jeff Beck used Magritte’s “The Listening Room” on the cover of his 1969 LP “Beck-Ola”. Is Magritte too ubiquitous to be uncanny? No, is the takeaway from “The Fifth Season”, an exhibition at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA). Displaying lesser-known work alongside some of his best-loved paintings, it shows that Magritte still has the power to surprise.

It is sometimes said that Surrealist paintings are disappointing up close; perhaps we see them so often in reproduction that by the time we see the real ones in a museum they’ve lost some of their strangeness. René Magritte’s paintings could fall into that trap. His bowler hats, apples, puffy clouds and pipes have popped up on coffee mugs, tote bags and dorm-room posters for decades. Not to mention album covers: Jeff Beck used Magritte’s “The Listening Room” on the cover of his 1969 LP “Beck-Ola”. Is Magritte too ubiquitous to be uncanny? No, is the takeaway from “The Fifth Season”, an exhibition at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA). Displaying lesser-known work alongside some of his best-loved paintings, it shows that Magritte still has the power to surprise.

In 1943 Magritte was living in Nazi-occupied Belgium. He was relatively well-known in artistic circles, though he was far from a household name. He had spent three years in Paris, where he was close with a group of painters which included André Breton, the leader of the Surrealist movement. He had developed his signature style: elegant canvases that challenged our ways of seeing. But the second world war had thrown him into a deep existential crisis. As he wrote to Breton: “The confusion and panic that Surrealism wanted to create in order to bring everything into question were achieved much better by the Nazi idiots than by us.” When everyday life had become horrifically surreal, why bother exploring the anxieties of the ordinary?

More here.

In July 3, 2014, Misty Mayo boarded a Greyhound bus bound for Los Angeles. Desperate to escape her hometown of Modesto in Stanislaus County, 300 miles north in California’s Central Valley, the 41-year-old thought the 4th of July fireworks in LA would be the perfect antidote. Even a mugging at the Modesto bus station didn’t deter her. When she arrived in LA the next morning with just a few dollars in her pocket, Misty immediately asked a police officer for directions to the fireworks display. She also knew she would need to find a Target pharmacy to refill her medication, but decided it could wait until later.

In July 3, 2014, Misty Mayo boarded a Greyhound bus bound for Los Angeles. Desperate to escape her hometown of Modesto in Stanislaus County, 300 miles north in California’s Central Valley, the 41-year-old thought the 4th of July fireworks in LA would be the perfect antidote. Even a mugging at the Modesto bus station didn’t deter her. When she arrived in LA the next morning with just a few dollars in her pocket, Misty immediately asked a police officer for directions to the fireworks display. She also knew she would need to find a Target pharmacy to refill her medication, but decided it could wait until later. You are now a highly successful public intellectual. In what ways has international recognition changed you?

You are now a highly successful public intellectual. In what ways has international recognition changed you? Aerial and satellite images of the colony living on the remote subantarctic island of Île aux Cochons, in the southern Indian Ocean, suggests the number of penguins has fallen from around 500,000 pairs in the 1980s, to just 60,000 pairs in photographs taken in 2015 and 2017.

Aerial and satellite images of the colony living on the remote subantarctic island of Île aux Cochons, in the southern Indian Ocean, suggests the number of penguins has fallen from around 500,000 pairs in the 1980s, to just 60,000 pairs in photographs taken in 2015 and 2017. We get the word “mesmerize” from a doctor named Franz Anton Mesmer, who in Paris in the late 18th century posited the existence of an invisible natural force connecting all living things — a force you could manipulate to physically affect another person.

We get the word “mesmerize” from a doctor named Franz Anton Mesmer, who in Paris in the late 18th century posited the existence of an invisible natural force connecting all living things — a force you could manipulate to physically affect another person. For anyone who has ever kept a diary, Sarah Manguso’s Ongoingness(first published in the US in 2015) will give pause for thought. The American writer kept a diary over 25 years and it was 800,000 words long. She elects not to publish a word of it in Ongoingness. It turns out she does not wish to look back at what she wrote. This absorbing book – brief as a breath – examines the need to record. It seems, even if she never spells it out, that writing the diary was a compulsive rebuffing of mortality. Like all diarists, she was trying to commandeer time. A diary gives the writer the illusion of stopping time in its tracks. And time – making her peace with its ongoingness – is Manguso’s obsession. Her book hints at diary-keeping as neurosis, a hoarding that is almost a syndrome, a malfunction, a grief at having no way to halt loss.

For anyone who has ever kept a diary, Sarah Manguso’s Ongoingness(first published in the US in 2015) will give pause for thought. The American writer kept a diary over 25 years and it was 800,000 words long. She elects not to publish a word of it in Ongoingness. It turns out she does not wish to look back at what she wrote. This absorbing book – brief as a breath – examines the need to record. It seems, even if she never spells it out, that writing the diary was a compulsive rebuffing of mortality. Like all diarists, she was trying to commandeer time. A diary gives the writer the illusion of stopping time in its tracks. And time – making her peace with its ongoingness – is Manguso’s obsession. Her book hints at diary-keeping as neurosis, a hoarding that is almost a syndrome, a malfunction, a grief at having no way to halt loss. When she moved from Michigan to be near her daughter in Cary, N.C., Bernadine Lewandowski insisted on renting an apartment five minutes away. Her daughter, Dona Jones, would have welcomed her mother into her own home, but “she’s always been very independent,” Ms. Jones said. Like most people in their 80s, Ms. Lewandowski contended with several chronic illnesses and took medication for osteoporosis, heart failure and pulmonary disease. Increasingly forgetful, she had been diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment. She used a cane for support as she walked around her apartment complex. Still, “she was trucking along just fine,” said her geriatrician, Dr. Maureen Dale. “Minor health issues here and there, but she was taking good care of herself.” But last September, Ms. Lewandowski entered a hospital after a compression fracture of her vertebra caused pain too intense to be managed at home. Over four days, she used nasal oxygen to help her breathe and received intravenous morphine for pain relief, later graduating to oxycodone tablets. Even after her discharge, the stress and disruptions of hospitalization — interrupted sleep, weight loss, mild delirium, deconditioning caused by days in bed — left her disoriented and weakened, a vulnerable state some researchers call “

When she moved from Michigan to be near her daughter in Cary, N.C., Bernadine Lewandowski insisted on renting an apartment five minutes away. Her daughter, Dona Jones, would have welcomed her mother into her own home, but “she’s always been very independent,” Ms. Jones said. Like most people in their 80s, Ms. Lewandowski contended with several chronic illnesses and took medication for osteoporosis, heart failure and pulmonary disease. Increasingly forgetful, she had been diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment. She used a cane for support as she walked around her apartment complex. Still, “she was trucking along just fine,” said her geriatrician, Dr. Maureen Dale. “Minor health issues here and there, but she was taking good care of herself.” But last September, Ms. Lewandowski entered a hospital after a compression fracture of her vertebra caused pain too intense to be managed at home. Over four days, she used nasal oxygen to help her breathe and received intravenous morphine for pain relief, later graduating to oxycodone tablets. Even after her discharge, the stress and disruptions of hospitalization — interrupted sleep, weight loss, mild delirium, deconditioning caused by days in bed — left her disoriented and weakened, a vulnerable state some researchers call “ When Mrs. William Shakespeare died on this August day in 1623, her family and friends believed they would lay her to eternal rest beside her renowned husband. They did not. They did inter an ordinary wife and mother, but the memory of her went out to become a Frankenstein monster, cut up and reassembled down the centuries. Few of the many makeovers done to Anne Hathaway Shakespeare since her passing have been flattering.

When Mrs. William Shakespeare died on this August day in 1623, her family and friends believed they would lay her to eternal rest beside her renowned husband. They did not. They did inter an ordinary wife and mother, but the memory of her went out to become a Frankenstein monster, cut up and reassembled down the centuries. Few of the many makeovers done to Anne Hathaway Shakespeare since her passing have been flattering. I’m tempted to describe Marion Milner’s book A Life of One’s Own as the missing manual for owners of a human mind. However, it’s not didactic or prescriptive. In fact, it’s useful mainly because it’s nothing like a manual or a self-help book. The book is more like an insightful travelogue by an articulate and honest observer with a gift for using vivid physical imagery and metaphors to describe her inner world.

I’m tempted to describe Marion Milner’s book A Life of One’s Own as the missing manual for owners of a human mind. However, it’s not didactic or prescriptive. In fact, it’s useful mainly because it’s nothing like a manual or a self-help book. The book is more like an insightful travelogue by an articulate and honest observer with a gift for using vivid physical imagery and metaphors to describe her inner world.

The 2020s will have a name. In the nursing homes of the future, Millennials’ grandchildren will hear all about the coming decade. Gran will remove her headset, loaded out with VR-entertainment and the latest in biometric tech, and she’ll tell the kids about the world as it was in the third decade of the 21st Century. For now, we look ahead to the Twenties, a decade certain to be charged with meaning, roaring in one way or another.

The 2020s will have a name. In the nursing homes of the future, Millennials’ grandchildren will hear all about the coming decade. Gran will remove her headset, loaded out with VR-entertainment and the latest in biometric tech, and she’ll tell the kids about the world as it was in the third decade of the 21st Century. For now, we look ahead to the Twenties, a decade certain to be charged with meaning, roaring in one way or another.

As a child, I feared dogs. A neighbor kept his German Shepherds, Heidi and Sarge, in a large pen along the alley. The yard and house, his parents’, were the biggest for many blocks. On the alley side, the chain link fence stood 10 feet. The dogs would charge out of their houses silently and hurl their bodies at the fence snarling and barking. I was caught unaware at the fence a few times. My stomach curdled and legs buckled. My mother’s family are dog people. My grandparents cared for a series of large overfed dogs who cavorted in the swamps surrounding their Massachusetts home and otherwise slumped under the kitchen table waiting for my grandmother to put together meals of breakfast scraps bound with maple syrup or for treats from a cookie jar on her counter. My uncles had shambling dogs who would leap into rough water off Cape Cod to retrieve balls from seaweed choked waves. As their fur dried, they smelled of sour salt water and general funk. At the rented house, they showed a gentle deference to humans and lolled on the grass or carpet while my cousins and I ate and talked.

As a child, I feared dogs. A neighbor kept his German Shepherds, Heidi and Sarge, in a large pen along the alley. The yard and house, his parents’, were the biggest for many blocks. On the alley side, the chain link fence stood 10 feet. The dogs would charge out of their houses silently and hurl their bodies at the fence snarling and barking. I was caught unaware at the fence a few times. My stomach curdled and legs buckled. My mother’s family are dog people. My grandparents cared for a series of large overfed dogs who cavorted in the swamps surrounding their Massachusetts home and otherwise slumped under the kitchen table waiting for my grandmother to put together meals of breakfast scraps bound with maple syrup or for treats from a cookie jar on her counter. My uncles had shambling dogs who would leap into rough water off Cape Cod to retrieve balls from seaweed choked waves. As their fur dried, they smelled of sour salt water and general funk. At the rented house, they showed a gentle deference to humans and lolled on the grass or carpet while my cousins and I ate and talked. This weekend, the New York Times’ print subscribers received something kind of crazy: A 66-page magazine with only a single article — and it’s on climate change. The long-form piece, written by Nathaniel Rich and titled “Losing Earth,”

This weekend, the New York Times’ print subscribers received something kind of crazy: A 66-page magazine with only a single article — and it’s on climate change. The long-form piece, written by Nathaniel Rich and titled “Losing Earth,”