Cordelia Fine in the Financial Times:

Cordelia Fine in the Financial Times:

In 2009, in the aftermath of the global financial crisis, the “Lehman Sisters” hypothesis was born. If only there had been more senior women in the banking industry, would the credit crunch have happened? Journalists, politicians and scientists speculated that the Lehman Sisters might indeed have saved us, on the grounds that “women managers are naturally more risk adverse,” as Neelie Kroes put it in a speech as European Commisioner for Competition in July 2007.

The idea that women — not so very long ago legally unable to own properties and securities — might be the saviours of the financial system may seem like a new and radical idea. But the notion’s heritage is an old one, both scientifically and politically.

Part of its cultural inheritance is a character I dubbed Testosterone Rex. You already know him. He was at that drinks party, telling us that testosterone is so potent that assumed average differences in testosterone levels between chief executives in mid-middle age versus late-middle age have a material, detectable influence on multi-party negotiations that involve discussions with the top management team, directions from the chair of the board and investors, and receipt of detailed financial advice from an investment bank. Testosterone Rex is, in short, the legend of that familiar scientific story that tells us risk-taking evolved more strongly in males than in females because of the greater reproductive advantages of status and resources for men in our ancestral past, and that these qualities are therefore wired into the male brain and fuelled by testosterone.

More here.

Richard V Reeves at Aeon:

Richard V Reeves at Aeon: Eric Levitz in NY Magazine [h/t: Leonard Benardo]:

Eric Levitz in NY Magazine [h/t: Leonard Benardo]: A common argument against Bergman is that he is fated for oblivion because his movies did not advance the art of film; they were

A common argument against Bergman is that he is fated for oblivion because his movies did not advance the art of film; they were

It’s hard to imagine, at this distance, how it must have been to be Aristotle in his own time: cutting-edge rather than foundational. We see him standing at the beginning of western philosophy and surveying something like virgin territory. Did it feel like that at the time? He didn’t know, obviously, that he was an Ancient – at the start of things, as we now see it, rather than, say, at their end. He was interdisciplinary before there were really disciplines to worry about. Look at him, romping across the territory of possible human knowledge like a big dog snapping at butterflies, or

It’s hard to imagine, at this distance, how it must have been to be Aristotle in his own time: cutting-edge rather than foundational. We see him standing at the beginning of western philosophy and surveying something like virgin territory. Did it feel like that at the time? He didn’t know, obviously, that he was an Ancient – at the start of things, as we now see it, rather than, say, at their end. He was interdisciplinary before there were really disciplines to worry about. Look at him, romping across the territory of possible human knowledge like a big dog snapping at butterflies, or  Lindsey Abel takes an anaesthetized mouse from a plastic container and lays it on the lab bench. With a syringe, she injects a slurry of pink cancer cells under the skin of the animal’s right flank. These cells once belonged to a person with tongue cancer, a former smoker whose disease recurred despite radiation and surgery. The mouse is the second rodent to harbour them, creating a model for cancer known as a patient-derived xenograft (PDX). The tumour that grows inside will provide cells that can be transferred to more mice. Abel has performed this procedure hundreds of time since she joined Randall Kimple’s lab at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Kimple, a radiation oncologist, uses PDX mice to carry out experiments on human tumours that would be impractical in people, such as testing new drugs and identifying factors that predict a good response to treatment. His lab has created more than 50 PDX mice since 2011. Kimple’s lab is not the only one doing this; PDX mice have exploded in popularity over the past decade and are beginning to supplant other techniques for modelling cancer in research and drug development, such as mice implanted with cancer cell lines. Because the models use fresh human tumour fragments rather than cells grown in a Petri dish, researchers have long hoped that PDXs would model tumour behaviour more accurately, and perhaps

Lindsey Abel takes an anaesthetized mouse from a plastic container and lays it on the lab bench. With a syringe, she injects a slurry of pink cancer cells under the skin of the animal’s right flank. These cells once belonged to a person with tongue cancer, a former smoker whose disease recurred despite radiation and surgery. The mouse is the second rodent to harbour them, creating a model for cancer known as a patient-derived xenograft (PDX). The tumour that grows inside will provide cells that can be transferred to more mice. Abel has performed this procedure hundreds of time since she joined Randall Kimple’s lab at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Kimple, a radiation oncologist, uses PDX mice to carry out experiments on human tumours that would be impractical in people, such as testing new drugs and identifying factors that predict a good response to treatment. His lab has created more than 50 PDX mice since 2011. Kimple’s lab is not the only one doing this; PDX mice have exploded in popularity over the past decade and are beginning to supplant other techniques for modelling cancer in research and drug development, such as mice implanted with cancer cell lines. Because the models use fresh human tumour fragments rather than cells grown in a Petri dish, researchers have long hoped that PDXs would model tumour behaviour more accurately, and perhaps

When the European Union slapped Google with a $5 billion antitrust fine recently, President Trump readied his exclamation points,

When the European Union slapped Google with a $5 billion antitrust fine recently, President Trump readied his exclamation points,  Lenore Palladino in Boston Review:

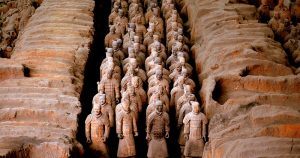

Lenore Palladino in Boston Review: In fact, the entire story of the Emperor and his Mausoleum is one of history, mystery, and discovery. History: the chronicles and annals of Chinese history help us to outline the straightforward historical record: this provides the basic starting point of the story. Mystery: since the emperor’s death there have been several mysteries, including the character of the emperor himself, the deliberately disguised location of the tomb, its real purpose and more recently the uncertain role of the terracotta warriors. Discovery: in the past this was serendipitous, as in the 1974 discovery of the warriors, but today it has become systematic and adopts advanced archaeological and scientific techniques which fill out the history and build on the mystery.

In fact, the entire story of the Emperor and his Mausoleum is one of history, mystery, and discovery. History: the chronicles and annals of Chinese history help us to outline the straightforward historical record: this provides the basic starting point of the story. Mystery: since the emperor’s death there have been several mysteries, including the character of the emperor himself, the deliberately disguised location of the tomb, its real purpose and more recently the uncertain role of the terracotta warriors. Discovery: in the past this was serendipitous, as in the 1974 discovery of the warriors, but today it has become systematic and adopts advanced archaeological and scientific techniques which fill out the history and build on the mystery.

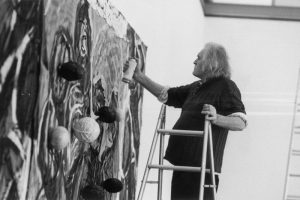

Mario Merz, a leading figure of the Italian avant-garde movement Arte Povera, first began to draw in prison, after being arrested in 1945 for his involvement with an anti-Facist group in Turin. He recorded his cell mate’s beard in continuous spirals, often without lifting his pencil off the paper. After his release, he painted leaves, animals and biomorphic shapes in a colourful Expressionist style. It wasn’t until the 1960s, though, that he began creating the three-dimensional works – using everyday objects and materials, such as wood, wool, glass, fruit, umbrellas and newspaper – for which he became famous.

Mario Merz, a leading figure of the Italian avant-garde movement Arte Povera, first began to draw in prison, after being arrested in 1945 for his involvement with an anti-Facist group in Turin. He recorded his cell mate’s beard in continuous spirals, often without lifting his pencil off the paper. After his release, he painted leaves, animals and biomorphic shapes in a colourful Expressionist style. It wasn’t until the 1960s, though, that he began creating the three-dimensional works – using everyday objects and materials, such as wood, wool, glass, fruit, umbrellas and newspaper – for which he became famous. The arts are “a space where we can give dignity to others while interrogating our own circumstances,” said Darren Walker, president of the Ford Foundation, at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History’s annual symposium, The Power of Giving: Philanthropy’s Impact on American Life. Held this spring, the program explored philanthropy’s impact on and through culture and the arts. As he reflected on the relationship between giving and the arts, Walker said that “throughout our history, we have seen artists and activists work hand in hand. We have seen art inspire and elevate whole movements for change.” As Walker suggests, music, storytelling, drama, and other arts have an emotional impact that motivates giving time and money to causes, while philanthropic appeals help artists attract audiences. To continue the conversation about the arts and giving, here’s a look at three objects that tell stories about how Americans used the arts to promote social change in the 1800s.

The arts are “a space where we can give dignity to others while interrogating our own circumstances,” said Darren Walker, president of the Ford Foundation, at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History’s annual symposium, The Power of Giving: Philanthropy’s Impact on American Life. Held this spring, the program explored philanthropy’s impact on and through culture and the arts. As he reflected on the relationship between giving and the arts, Walker said that “throughout our history, we have seen artists and activists work hand in hand. We have seen art inspire and elevate whole movements for change.” As Walker suggests, music, storytelling, drama, and other arts have an emotional impact that motivates giving time and money to causes, while philanthropic appeals help artists attract audiences. To continue the conversation about the arts and giving, here’s a look at three objects that tell stories about how Americans used the arts to promote social change in the 1800s. After I came back from Australia, I wondered about a large bauxite mine that I’d heard of, where termites had rehabilitated the land. I wondered if there was more to the story than the fact that they fertilized the soil and recycled the grasses. There seemed to be a gap between bugs dropping a few extra nitrogen molecules in their poo and the creation of a whole forest. What were they doing down there? I started going through my files, looking for people working on landscapes. This led me to the work of a mathematician named Corina Tarnita and an ecologist named Rob Pringle. When I contacted her, Corina had just moved to Princeton from Harvard and, with Rob, had set about using mathematical modeling to figure out what termites were doing in dry landscapes in Kenya. As it happened, I had interviewed Rob back in 2010, when he and a team published a paper on the role of termites in the African savanna ecosystems that are home to elephants and giraffes.

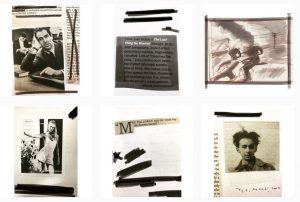

After I came back from Australia, I wondered about a large bauxite mine that I’d heard of, where termites had rehabilitated the land. I wondered if there was more to the story than the fact that they fertilized the soil and recycled the grasses. There seemed to be a gap between bugs dropping a few extra nitrogen molecules in their poo and the creation of a whole forest. What were they doing down there? I started going through my files, looking for people working on landscapes. This led me to the work of a mathematician named Corina Tarnita and an ecologist named Rob Pringle. When I contacted her, Corina had just moved to Princeton from Harvard and, with Rob, had set about using mathematical modeling to figure out what termites were doing in dry landscapes in Kenya. As it happened, I had interviewed Rob back in 2010, when he and a team published a paper on the role of termites in the African savanna ecosystems that are home to elephants and giraffes. What you see below are images from my notebooks, recently posted on my

What you see below are images from my notebooks, recently posted on my