Adam Kirsch in The Nation:

Adam Kirsch in The Nation:

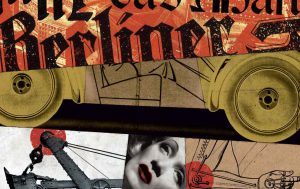

What is Alexanderplatz in Berlin?” asked Walter Benjamin in his review of Alfred Döblin’s Berlin Alexanderplatz. As Döblin’s original readers would have known quite well, Alexanderplatz is a square in central Berlin that serves as a transportation hub and as the anchor of a commercial district. But for Benjamin, the key fact about Alexanderplatz in 1929, when Döblin’s book was published, was that it was a vast construction site, “where for the last two years the most violent transformations have been taking place, where excavators and jackhammers have been continuously at work, where the ground trembles under the impact of their blows.”

Alexanderplatz, then, was the scene of a modern metropolis coming dangerously and discordantly into being—just as Berlin does in Döblin’s novel. In his afterword, Michael Hofmann, who gives us an impressively wild and fearless new translation of the book, credits it with founding “the idea of modern city literature altogether.” This might be an exaggeration of its uniqueness: Any English-speaking reader will immediately think of James Joyce and John Dos Passos as parallels, if not necessarily precursors. Like them, Döblin makes use of stream of consciousness, collage and montage, the collision of discourses and registers. One might also think of T.S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land,” with its hypnotic vision of London as an “Unreal City” and the crowds of the living dead flowing over London Bridge. But when the city in question is Weimar-era Berlin, the urban chaos and dread take on new dimensions. In Berlin Alexanderplatz, we are plunged into a cauldron of alienation, violence, and social breakdown that would, just a few years after Döblin wrote his novel, deliver all of Germany into the hands of the Nazis.

More here.