Category: Recommended Reading

Public Benefit, Incorporated

Lenore Palladino in Boston Review:

Lenore Palladino in Boston Review:

The stakeholder model of corporate governance would redesign governance so that all stakeholders in our economy (workers, customers, and the public) have a chance to benefit as corporations create profit. It is simultaneously radical and incremental by promising to remake our economy with some straightforward legal shifts. Though there are plenty of variations, three substantive changes to corporate governance are necessary.

The first change is to disallow corporations from forming for any lawful purpose. Corporations should be required by statute to have as their purpose “creating general public benefit,” which is the language that benefit corporations such as Kickstarter and Patagonia use. Benefit corporations are companies that have chosen to be governed by a new kind of law that requires a public benefit purpose and accountability to stakeholders. Benefit corporation status is permissive—right now, corporations have to choose it. Corporate law should be changed so that all corporations—creatures of the state—must create a general public benefit. This would, at minimum, allow some ability to challenge corporate externalities that have disastrous social consequences.

The second change is to mandate that employees, and perhaps other stakeholders, have elected representatives on the board to balance the interests among those making major decisions of the corporation. The third is to make the fiduciary duties of board members—their obligation to be loyal and to make decisions with the interests of the corporation, not themselves, in mind—applicable to a variety of stakeholders, not merely the shareholders who have been actively trading on the secondary markets.

More here.

One of The Greatest Archeological Mysteries of All Time

Edward Burman at Literary Hub:

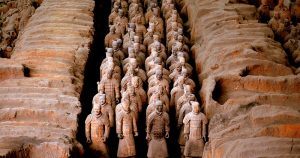

In fact, the entire story of the Emperor and his Mausoleum is one of history, mystery, and discovery. History: the chronicles and annals of Chinese history help us to outline the straightforward historical record: this provides the basic starting point of the story. Mystery: since the emperor’s death there have been several mysteries, including the character of the emperor himself, the deliberately disguised location of the tomb, its real purpose and more recently the uncertain role of the terracotta warriors. Discovery: in the past this was serendipitous, as in the 1974 discovery of the warriors, but today it has become systematic and adopts advanced archaeological and scientific techniques which fill out the history and build on the mystery.

In fact, the entire story of the Emperor and his Mausoleum is one of history, mystery, and discovery. History: the chronicles and annals of Chinese history help us to outline the straightforward historical record: this provides the basic starting point of the story. Mystery: since the emperor’s death there have been several mysteries, including the character of the emperor himself, the deliberately disguised location of the tomb, its real purpose and more recently the uncertain role of the terracotta warriors. Discovery: in the past this was serendipitous, as in the 1974 discovery of the warriors, but today it has become systematic and adopts advanced archaeological and scientific techniques which fill out the history and build on the mystery.

One of the foreigners mentioned above, the French poet, novelist, sinologist, and doctor Victor Segalen, was not the first to photograph the tumulus, but he is the only one to have recorded his “discovery.”

more here.

In Voltaire’s Garden

Isabelle Mayault at the LRB:

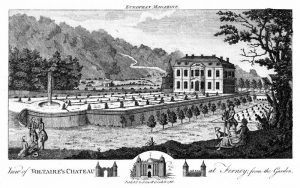

The château at Ferney recently reopened to the public after three years of restoration and refurbishment. Except for the planes high above the lawns, flying in and out of Geneva airport, not much has changed at the château since Voltaire lived here between 1760 and his death in 1778. It’s easy to imagine him taking an afternoon stroll among the plane trees, Mont Blanc in the background, after a morning in bed dictating his voluminous correspondence to his private secretary. During his twenty years at Ferney, he wrote 6000 letters.

When Voltaire first visited, Ferney was a small village of 130 inhabitants, but it had at least one advantage to a polemicist used to falling out with the authorities: its strategic location just on the French side of the border with the republic of Geneva.

more here.

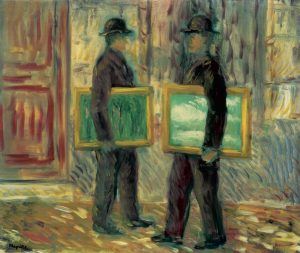

Serenity and Menace in The Works of Mario Merz

Mika Ross-Southall at the TLS:

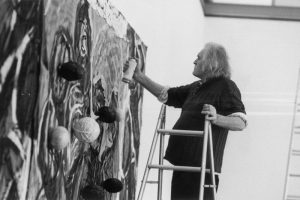

Mario Merz, a leading figure of the Italian avant-garde movement Arte Povera, first began to draw in prison, after being arrested in 1945 for his involvement with an anti-Facist group in Turin. He recorded his cell mate’s beard in continuous spirals, often without lifting his pencil off the paper. After his release, he painted leaves, animals and biomorphic shapes in a colourful Expressionist style. It wasn’t until the 1960s, though, that he began creating the three-dimensional works – using everyday objects and materials, such as wood, wool, glass, fruit, umbrellas and newspaper – for which he became famous.

Mario Merz, a leading figure of the Italian avant-garde movement Arte Povera, first began to draw in prison, after being arrested in 1945 for his involvement with an anti-Facist group in Turin. He recorded his cell mate’s beard in continuous spirals, often without lifting his pencil off the paper. After his release, he painted leaves, animals and biomorphic shapes in a colourful Expressionist style. It wasn’t until the 1960s, though, that he began creating the three-dimensional works – using everyday objects and materials, such as wood, wool, glass, fruit, umbrellas and newspaper – for which he became famous.

“It is necessary to use anything whatsoever from life in art”, Merz said, “not to reject things because one thinks that life and art are mutually exclusive.” This sentiment is clear in the twelve pieces inspired by the protest movements of 1968, which are currently on show at the Fondazione Merz in Turin.

more here.

Thursday Poem

I am Waiting

I am waiting for my case to come up

and I am waiting

for a rebirth of wonder

and I am waiting for someone

to really discover America

and wail

and I am waiting

for the discovery

of a new symbolic western frontier

and I am waiting

for the American Eagle

to really spread its wings

and straighten up and fly right

and I am waiting

for the Age of Anxiety

to drop dead

and I am waiting

for the war to be fought

which will make the world safe

for anarchy

and I am waiting

for the final withering away

of all governments

and I am perpetually awaiting

a rebirth of wonder

How Do the Arts Promote Social Change?

Amanda Moniz in Smithsonian:

The arts are “a space where we can give dignity to others while interrogating our own circumstances,” said Darren Walker, president of the Ford Foundation, at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History’s annual symposium, The Power of Giving: Philanthropy’s Impact on American Life. Held this spring, the program explored philanthropy’s impact on and through culture and the arts. As he reflected on the relationship between giving and the arts, Walker said that “throughout our history, we have seen artists and activists work hand in hand. We have seen art inspire and elevate whole movements for change.” As Walker suggests, music, storytelling, drama, and other arts have an emotional impact that motivates giving time and money to causes, while philanthropic appeals help artists attract audiences. To continue the conversation about the arts and giving, here’s a look at three objects that tell stories about how Americans used the arts to promote social change in the 1800s.

The arts are “a space where we can give dignity to others while interrogating our own circumstances,” said Darren Walker, president of the Ford Foundation, at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History’s annual symposium, The Power of Giving: Philanthropy’s Impact on American Life. Held this spring, the program explored philanthropy’s impact on and through culture and the arts. As he reflected on the relationship between giving and the arts, Walker said that “throughout our history, we have seen artists and activists work hand in hand. We have seen art inspire and elevate whole movements for change.” As Walker suggests, music, storytelling, drama, and other arts have an emotional impact that motivates giving time and money to causes, while philanthropic appeals help artists attract audiences. To continue the conversation about the arts and giving, here’s a look at three objects that tell stories about how Americans used the arts to promote social change in the 1800s.

In the 1840s, the popular Hutchinson Family Singers from New Hampshire introduced music to the developing antislavery movement. As the sheet music for “The Grave of Bonaparte” suggests, the singers were concerned about freedom in other forms and many places, but they had their biggest impact on the American antislavery movement. Performing before integrated audiences, siblings Judson, John, Asa, and Abby—who were managed by their brother Jesse—helped nurture opposition to slavery among those not exposed to its evils. They also helped build far-flung antislavery networks thanks to their travel and the newspaper coverage of their events. Moreover, the success of their antislavery songs showed that the cause had commercial appeal. Works such as the novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin would cater to that appeal–and help further develop antislavery sentiment. In addition to their contributions to reform causes, the group shaped American musical identity. At a time when Americans favored European musicians, the Hutchinson Family Singers spurred new interest in American music.

More here.

How Termites Shape the Natural World

Lisa Morgonelli in Scientific American:

After I came back from Australia, I wondered about a large bauxite mine that I’d heard of, where termites had rehabilitated the land. I wondered if there was more to the story than the fact that they fertilized the soil and recycled the grasses. There seemed to be a gap between bugs dropping a few extra nitrogen molecules in their poo and the creation of a whole forest. What were they doing down there? I started going through my files, looking for people working on landscapes. This led me to the work of a mathematician named Corina Tarnita and an ecologist named Rob Pringle. When I contacted her, Corina had just moved to Princeton from Harvard and, with Rob, had set about using mathematical modeling to figure out what termites were doing in dry landscapes in Kenya. As it happened, I had interviewed Rob back in 2010, when he and a team published a paper on the role of termites in the African savanna ecosystems that are home to elephants and giraffes.

After I came back from Australia, I wondered about a large bauxite mine that I’d heard of, where termites had rehabilitated the land. I wondered if there was more to the story than the fact that they fertilized the soil and recycled the grasses. There seemed to be a gap between bugs dropping a few extra nitrogen molecules in their poo and the creation of a whole forest. What were they doing down there? I started going through my files, looking for people working on landscapes. This led me to the work of a mathematician named Corina Tarnita and an ecologist named Rob Pringle. When I contacted her, Corina had just moved to Princeton from Harvard and, with Rob, had set about using mathematical modeling to figure out what termites were doing in dry landscapes in Kenya. As it happened, I had interviewed Rob back in 2010, when he and a team published a paper on the role of termites in the African savanna ecosystems that are home to elephants and giraffes.

I took the train to Princeton to meet them in early 2014. By that time I’d been following termites for six years, and I’d pretty much given up on two ideas that motivated me early on: understanding the relation between local changes and global effects—that concept of global to local that dogs complexity theorists—and the development of technology that could potentially “save the world.” But through mathematical models, Corina and Rob and their teams eventually delivered a version of those things. And it was purely a bonus that they might have even solved the mystery of the fairy circles.

More here.

Wednesday, August 8, 2018

Amitava Kumar’s Notebooks

Amitava Kumar in Granta:

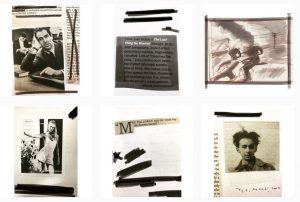

What you see below are images from my notebooks, recently posted on my Instagram. Clippings, quotes, sketches. These notebooks represent the many years I have lived with the dream of a book that turned into Immigrant, Montana. When I went to Yaddo on a writing residency one summer, it was the notebooks that I looked through each morning and night – these notebooks are a visual reminder of all the bits and pieces I was thinking about when writing this novel.

What you see below are images from my notebooks, recently posted on my Instagram. Clippings, quotes, sketches. These notebooks represent the many years I have lived with the dream of a book that turned into Immigrant, Montana. When I went to Yaddo on a writing residency one summer, it was the notebooks that I looked through each morning and night – these notebooks are a visual reminder of all the bits and pieces I was thinking about when writing this novel.

What these pictures do not show is a page from a narrow, reporter’s notebook that I used to have when finishing graduate school. Sitting in an Amtrak railcar many years ago, on my way to a Modern Language Association meeting in New York, where I’d be interviewed and eventually be given my first job teaching in an English department, I wrote the following line: ‘The red-bottomed monkeys climbed down the branches of the tamarind tree to peel the oranges left unattended on Lotan Mamaji’s house.’ I was recalling a childhood memory involving a monkey, a gun and my infant cousin still in her crib. This first sentence later turned into a short-story – I workshopped it in a small writing group, my first, which included a twenty-one-year-old Cheryl Strayed – and then, years later, it became the opening episode in my new novel.

The picture on the top left is of Philip Roth. There’s a story there.

More here.

Ted Nordhaus Is Wrong: We Are Exceeding Earth’s Carrying Capacity

Richard Heinberg in Undark:

IN HIS ARTICLE, “The Earth’s Carrying Capacity for Human Life is Not Fixed,” Ted Nordhaus, co-founder of the Breakthrough Institute, a California-based energy and environment think tank, seeks to enlist readers in his optimistic vision of the future. It’s a future in which there are many more people on the planet and each enjoys a high standard of living, while environmental impacts are reduced. It’s a cheery vision.

IN HIS ARTICLE, “The Earth’s Carrying Capacity for Human Life is Not Fixed,” Ted Nordhaus, co-founder of the Breakthrough Institute, a California-based energy and environment think tank, seeks to enlist readers in his optimistic vision of the future. It’s a future in which there are many more people on the planet and each enjoys a high standard of living, while environmental impacts are reduced. It’s a cheery vision.

If only it were plausible.

Nordhaus’s argument hinges on dismissing the longstanding biological concept of “carrying capacity” — the number of organisms an environment can support without becoming degraded. “Applied to ecology, the concept [of carrying capacity] is problematic,” Nordhaus writes, arguing in a nutshell that the planet’s ability to support human civilization can be, one presumes, infinitely tweaked through a combination of social and physical engineering.

Few actual ecologists, however, would agree.

More here.

The Death of the Author and the End of Empathy

Heather Mac Donald in Quillette:

In 2015, President Obama described the Nation as “more than a magazine—it’s a crucible of ideas.” If it was ever entitled to this descriptor, it isn’t anymore. Academic identity politics may be importing an obsession with phantom victimhood into the business world and the media, but The Nation’s editors are now taking aim at language itself, reducing the complexity of human communication to a primitive understanding of words.

In late July, the magazine’s poetry editors issued a groveling apology for a poem they had published earlier that month. “How-To,” by Anders Carlson-Wee, was an ironic critique of social hierarchies, couched as a manual for successful panhandling: “If you got hiv, say aids. If you a girl,/say you’re pregnant,” the poem opened. It went on to suggest begging gambits for other presumed outsider groups, including the handicapped: “If you’re crippled don’t/flaunt it. Let em think they’re good enough/Christians to notice.” The poem, in its entirety, reads as follows:

If you got hiv, say aids. If you a girl,

say you’re pregnant—nobody gonna lower

themselves to listen for the kick. People

passing fast. Splay your legs, cock a knee

funny. It’s the littlest shames they’re likely

to comprehend. Don’t say homeless, they know

you is. What they don’t know is what opens

a wallet, what stops em from counting

what they drop. If you’re young say younger.

Old say older. If you’re crippled don’t

flaunt it. Let em think they’re good enough

Christians to notice. Don’t say you pray,

say you sin. It’s about who they believe

they is. You hardly even there.

The word ‘crippled’ and Carlson-Wee’s use of black street dialect set off reader hysteria. Editors Stephanie Burt and Carmen Giménez Smith penitently announced that the poem contained “disparaging and ableist language that has given offense and caused harm to members of several communities.” (This maudlin invocation of ‘harm’ in response to speech is the fastest growing academic export into the non-academic world.) “We made a serious mistake [and] are sorry for the pain we have caused to the many communities affected by this poem,” Burt and Giménez Smith continued. They had originally read the poem, they said, as a “profane, over-the-top attack on the ways in which members of many groups are asked, or required, to perform the work of marginalization.” No more, however: “We can no longer read the poem that way.”

More here.

James Harris Simons, Billionaire Mathematician

René Magritte still has the power to surprise

Sophie Haigney in More Intelligent Life:

It is sometimes said that Surrealist paintings are disappointing up close; perhaps we see them so often in reproduction that by the time we see the real ones in a museum they’ve lost some of their strangeness. René Magritte’s paintings could fall into that trap. His bowler hats, apples, puffy clouds and pipes have popped up on coffee mugs, tote bags and dorm-room posters for decades. Not to mention album covers: Jeff Beck used Magritte’s “The Listening Room” on the cover of his 1969 LP “Beck-Ola”. Is Magritte too ubiquitous to be uncanny? No, is the takeaway from “The Fifth Season”, an exhibition at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA). Displaying lesser-known work alongside some of his best-loved paintings, it shows that Magritte still has the power to surprise.

It is sometimes said that Surrealist paintings are disappointing up close; perhaps we see them so often in reproduction that by the time we see the real ones in a museum they’ve lost some of their strangeness. René Magritte’s paintings could fall into that trap. His bowler hats, apples, puffy clouds and pipes have popped up on coffee mugs, tote bags and dorm-room posters for decades. Not to mention album covers: Jeff Beck used Magritte’s “The Listening Room” on the cover of his 1969 LP “Beck-Ola”. Is Magritte too ubiquitous to be uncanny? No, is the takeaway from “The Fifth Season”, an exhibition at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA). Displaying lesser-known work alongside some of his best-loved paintings, it shows that Magritte still has the power to surprise.

In 1943 Magritte was living in Nazi-occupied Belgium. He was relatively well-known in artistic circles, though he was far from a household name. He had spent three years in Paris, where he was close with a group of painters which included André Breton, the leader of the Surrealist movement. He had developed his signature style: elegant canvases that challenged our ways of seeing. But the second world war had thrown him into a deep existential crisis. As he wrote to Breton: “The confusion and panic that Surrealism wanted to create in order to bring everything into question were achieved much better by the Nazi idiots than by us.” When everyday life had become horrifically surreal, why bother exploring the anxieties of the ordinary?

More here.

Wednesday Poem

Blackberry Authorities

When I first came out to the country

…… I knew nothing. I watched

as people planted, harvested, picked

…… the berries, explained

the weather, tended the ducks and horses.

When I first came out to the country

…… my mind emptied and I

liked it that way. My mind was like a sky

…… without clouds, a summer sky

with several birds flapping across a field

…… on the eastern horizon.

I liked the slowness of things. The empty

…… town, the lake stillness,

the man I met who seemed contented, who

…… sat and talked in the dusk

about why he had chosen this long ago.

I did better dreaming then. the colors

…… were clear. I found something

important in myself: capacity for renewal.

…… And at night, the sky so intense.

Clear incredible stars! Almost another earth.

But now I see there are judgments here.

…… This way of planting or that.

The arguments about fertilizers and organics;

…… problems of time, figuring how

to allocate what we have. So many matters

…… to fasten on and dissect.

That’s the way it is with revelations,

…… If you live it out, you start

thinking, examining. The mind cries out

…… for materials to play with.

Right now, in fact, I’m excited about

…… several new vines and waiting

for the blackberry authorities to arrive.

.

by Lou Lipsitz

from Seeking the Hook

Signal Books 1997

How Can You Treat Someone Who Doesn’t Think They’re Mentally Ill?

Carrie Arnold in Tonic:

In July 3, 2014, Misty Mayo boarded a Greyhound bus bound for Los Angeles. Desperate to escape her hometown of Modesto in Stanislaus County, 300 miles north in California’s Central Valley, the 41-year-old thought the 4th of July fireworks in LA would be the perfect antidote. Even a mugging at the Modesto bus station didn’t deter her. When she arrived in LA the next morning with just a few dollars in her pocket, Misty immediately asked a police officer for directions to the fireworks display. She also knew she would need to find a Target pharmacy to refill her medication, but decided it could wait until later.

In July 3, 2014, Misty Mayo boarded a Greyhound bus bound for Los Angeles. Desperate to escape her hometown of Modesto in Stanislaus County, 300 miles north in California’s Central Valley, the 41-year-old thought the 4th of July fireworks in LA would be the perfect antidote. Even a mugging at the Modesto bus station didn’t deter her. When she arrived in LA the next morning with just a few dollars in her pocket, Misty immediately asked a police officer for directions to the fireworks display. She also knew she would need to find a Target pharmacy to refill her medication, but decided it could wait until later.

Later came and went. With no money in a strange city, Misty found the bus system too confusing to navigate. The longer she went without her cocktail of antipsychotics to keep the worst symptoms of her schizoaffective disorder at bay, the more difficult it became to remember that she even needed medication. In the sweltering July heat, Misty roamed the streets of Santa Monica, trying to grab a few minutes of shut-eye where she could. Mostly, she was too afraid to sleep. Misty’s worsening mental state left her combative and paranoid. Her memories of this time are vague at best, but hospital records show a series of psychiatric hospitalizations during July and August. She was arrested at least once. By now, Misty no longer recognized that she had a health problem. Not surprisingly, she didn’t take her medications once out of hospital, and the cycle repeated itself over and over. Back in Modesto, Misty’s mother, Linda, felt her worry turn to panic as the days passed without word from her daughter. She filed a missing persons report, and the next time police picked up Misty for her latest infraction, Linda got a phone call.

More here.

Tuesday, August 7, 2018

Yuval Noah Harari: ‘The idea of free information is extremely dangerous’

Andrew Anthony in The Guardian:

You are now a highly successful public intellectual. In what ways has international recognition changed you?

You are now a highly successful public intellectual. In what ways has international recognition changed you?

Well I have much less time. I find myself travelling around the world and going to conferences and giving interviews, basically repeating what I think I already know, and having less and less time to research new stuff. Just a few years ago I was an anonymous professor of history specialising in medieval history and my audience was about five people around the world who read my articles. So it’s quite shocking to be now in a position that I write something and there is a potential of millions of people will read it. Overall I’m happy with what’s happened. You don’t want to just speak up, you also want to be heard. It’s a privilege that I now have such an audience.

How do you set about deciding what are the most pressing questions of the age?

Actually in a way this was the easiest book to write because it was written in conversation with the public. Its contents were decided largely by the kinds of questions I was asked in interviews and public appearances. My two previous books were about the long-term past of humankind and the long-term future. But you can’t live in the past and you can’t live in the future. You can live only in the present. So unless you can take these long-term insights and say something abut the immigration crisis, or Brexit or fake news, what’s the point?

More here.

World’s largest king penguin colony collapses by almost 90% in space of 35 years

Harry Cockburn in The Independent:

Aerial and satellite images of the colony living on the remote subantarctic island of Île aux Cochons, in the southern Indian Ocean, suggests the number of penguins has fallen from around 500,000 pairs in the 1980s, to just 60,000 pairs in photographs taken in 2015 and 2017.

Aerial and satellite images of the colony living on the remote subantarctic island of Île aux Cochons, in the southern Indian Ocean, suggests the number of penguins has fallen from around 500,000 pairs in the 1980s, to just 60,000 pairs in photographs taken in 2015 and 2017.

Until now, it was regarded as the second-largest colony of penguins in the world, after one on Zavodovski Island in the South Sandwich Islands, where the slopes of an active volcano are home to around two million chinstrap penguins.

Scientists have not yet identified why the population of king penguins on Île aux Cochons has shrunk so dramatically, but they noted that it is not possible for the birds have migrated elsewhere, as there are no other islands suitable for them to inhabit within striking distance.

More here.

Donald Trump, Mesmerist

Emily Ogden in the New York Times:

We get the word “mesmerize” from a doctor named Franz Anton Mesmer, who in Paris in the late 18th century posited the existence of an invisible natural force connecting all living things — a force you could manipulate to physically affect another person.

We get the word “mesmerize” from a doctor named Franz Anton Mesmer, who in Paris in the late 18th century posited the existence of an invisible natural force connecting all living things — a force you could manipulate to physically affect another person.

Mesmer’s work inspired the stage hypnotists of mid-19th-century America. Before rapt audiences, these “mesmerists” used carefully choreographed gestures to lull their subjects into a state of credulous obedience. As the practitioner John Bovee Dods wrote in the 1850s, a mesmerist could make an entranced volunteer see “that a hat is a halibut or flounder; a handkerchief is a bird, child or rabbit; or that the moon or a star falls on a person in the audience, and sets him on fire.”

In our historical moment, the mesmerists are worth considering, for they were frequently debunked but the debunkings rarely had much of an effect. Just as the repeated corrections of President Trump’s falsehoods have failed to discourage him or his supporters, so too the mesmerists escaped their exposés unharmed.

More here.

Brian Greene: Why is our universe fine-tuned for life?

Ongoingness and 300 Arguments

Kate Kellaway in The Guardian:

For anyone who has ever kept a diary, Sarah Manguso’s Ongoingness(first published in the US in 2015) will give pause for thought. The American writer kept a diary over 25 years and it was 800,000 words long. She elects not to publish a word of it in Ongoingness. It turns out she does not wish to look back at what she wrote. This absorbing book – brief as a breath – examines the need to record. It seems, even if she never spells it out, that writing the diary was a compulsive rebuffing of mortality. Like all diarists, she was trying to commandeer time. A diary gives the writer the illusion of stopping time in its tracks. And time – making her peace with its ongoingness – is Manguso’s obsession. Her book hints at diary-keeping as neurosis, a hoarding that is almost a syndrome, a malfunction, a grief at having no way to halt loss.

For anyone who has ever kept a diary, Sarah Manguso’s Ongoingness(first published in the US in 2015) will give pause for thought. The American writer kept a diary over 25 years and it was 800,000 words long. She elects not to publish a word of it in Ongoingness. It turns out she does not wish to look back at what she wrote. This absorbing book – brief as a breath – examines the need to record. It seems, even if she never spells it out, that writing the diary was a compulsive rebuffing of mortality. Like all diarists, she was trying to commandeer time. A diary gives the writer the illusion of stopping time in its tracks. And time – making her peace with its ongoingness – is Manguso’s obsession. Her book hints at diary-keeping as neurosis, a hoarding that is almost a syndrome, a malfunction, a grief at having no way to halt loss.

As an essayist (for the New York Times magazine, the Paris Review, the New York Review of Books), Manguso makes it plain she cannot forget the book she may never write – it haunts her like a long shadow. This is referred to more than once in 300 Arguments, which is even shorter than Ongoingness – a collection of aphorisms (“Think of this as a short book composed entirely of what I hoped would be a long book’s quotable passages,” is one regretful example). A good aphorism is a raft: it carries you. Even – particularly – bitter and twisted ones should have a perversely feelgood factor. In its concision, an aphorism could not be further from the unexpurgated journal Manguso wrote in the present tense – another denial of passing time. The best aphorisms are witty. When Oscar Wilde writes: “It is only shallow people who do not judge by appearances”, he delicately tilts a thought on its axis, turning the received wisdom inside out. Dorothy Parker turns the tables similarly when she quips: “If you want to know what God thinks of money, just look at the people he gave it to.” George Bernard Shaw’s “Those who cannot change their minds cannot change anything” is a playful reminder of the tyranny of certainty expressed without doubt.

More here.