by Bill Murray

Hyvä asiakkaamme,

Ethän käytä huoneiston takkaa.

Se on tällä hetkellä epäkunnossa

Ja savuttaa sisään.

Dear customer,

Please don’t use the fireplace. It is for the moment out of order and the smoke comes into the apartment.

Now wait a minute. We might need that fireplace in Lapland in December. Just now it’s three degrees (-16C) outside. The nice lady couldn’t be more sympathetic, but they just manage the place. Fixing the fireplace requires funding that can’t be organized until we are gone.

She promises we’ll stay warm thanks to a magnificent heater, a sauna and the eteinen, one of those icebox-sized northern anterooms that separate the outside from the living area. I have fun with the translation, though. I imagine that fool Ethän has busted the damned fireplace again.

• • •

Welcome to Saariselkä, Finland, where it’s dark in the morning, briefly dusk, then dark again for the rest of the day. The sun never aspires to the horizon. Fifty miles up the road Finland, Norway and Russia meet at the top of Europe.

But look around. It’s entirely possible to live inside the Arctic Circle. It takes a little more bundling up and all, and you need a plan before you go outside. No idle standing around out there.

There are even advantages. Trailing your groceries after you on a sled, a pulkka, is easier than carrying them. There’s a word for the way you walk: köpöttää. It means taking tiny steps the way you do to keep your balance on an icy sidewalk.

Plus, other humans live here, too, and they seem to get along just fine. Infrastructure’s good, transport in big, heavy, late model SUVs, a community of 2600 people, all of them attractive, all of whom look just like each other.

I imagined “selling time shares in Lapland” was a punch line, but it’s an actual thing. A jammed-full Airbus delivered us from Helsinki, one of three flights every day to Rovaniemi. Read more »

Roxane Gay’s Hunger is very, very good—the rare memoir that doubles as page-turner. I’m writing this on a flight (Gay’s passages on airplane issues are some of her best: the seatbelt extenders, having to buy two tickets) and the woman across the aisle is reading Difficult Women. “Book Twins!” she just said happily. This never happens. That Gay has reached so many is testament to her skill with empathetic connection. She writes early in Hunger that her “life is split in two, cleaved not so neatly. There is the before and after. Before I gained weight. After I gained weight. Before I was raped. After I was raped.”

Roxane Gay’s Hunger is very, very good—the rare memoir that doubles as page-turner. I’m writing this on a flight (Gay’s passages on airplane issues are some of her best: the seatbelt extenders, having to buy two tickets) and the woman across the aisle is reading Difficult Women. “Book Twins!” she just said happily. This never happens. That Gay has reached so many is testament to her skill with empathetic connection. She writes early in Hunger that her “life is split in two, cleaved not so neatly. There is the before and after. Before I gained weight. After I gained weight. Before I was raped. After I was raped.” Tim Watson’s Culture Writing surveys the border between anthropology and literature in the years following World War II. Watson provides illuminating readings of British social anthropology in relation to novels by Barbara Pym, and of North American cultural anthropology in relation to novels by Ursula Le Guin and Saul Bellow. There are also chapters on Édouard Glissant and Michel Leiris, working in the French tradition (in which the border between literary and ethnographic writing was configured differently than it was in the Anglo-American tradition). While anthropologists will find much of value in Watson’s individual readings, they may find his broader sketch of their disciplinary history to be seriously askew, as I shall suggest in what follows.

Tim Watson’s Culture Writing surveys the border between anthropology and literature in the years following World War II. Watson provides illuminating readings of British social anthropology in relation to novels by Barbara Pym, and of North American cultural anthropology in relation to novels by Ursula Le Guin and Saul Bellow. There are also chapters on Édouard Glissant and Michel Leiris, working in the French tradition (in which the border between literary and ethnographic writing was configured differently than it was in the Anglo-American tradition). While anthropologists will find much of value in Watson’s individual readings, they may find his broader sketch of their disciplinary history to be seriously askew, as I shall suggest in what follows.

What happens when a scientific journal publishes information that turns out to be false? A fracas over a recent

What happens when a scientific journal publishes information that turns out to be false? A fracas over a recent  What will a Corbyn government actually do? Brexit aside, British politics has no bigger known unknown. The prospect fills the rich with fear and the left with hope. Both sides assume that Prime Minister

What will a Corbyn government actually do? Brexit aside, British politics has no bigger known unknown. The prospect fills the rich with fear and the left with hope. Both sides assume that Prime Minister  THERE HAS ALWAYS BEEN a lot of hand-wringing around erotica, especially erotica that centers on female submission. Feminists worry that it perpetuates harmful gender dynamics, while conservatives shudder at the frank depictions of female sexuality. Intellectuals usually dismiss it as smut. In the meantime, millions of people — mostly women — gobble it up. The box office success of Fifty Shades Freed, the third installment in the Hollywood trilogy based on E. L. James’s best-selling BDSM romance series, is only the latest example. How is it, wondered pundits, that this particular movie is a hit at the height of the #MeToo movement? Why are women flocking to see a film about a rich, white man dominating a much younger, much less powerful woman?

THERE HAS ALWAYS BEEN a lot of hand-wringing around erotica, especially erotica that centers on female submission. Feminists worry that it perpetuates harmful gender dynamics, while conservatives shudder at the frank depictions of female sexuality. Intellectuals usually dismiss it as smut. In the meantime, millions of people — mostly women — gobble it up. The box office success of Fifty Shades Freed, the third installment in the Hollywood trilogy based on E. L. James’s best-selling BDSM romance series, is only the latest example. How is it, wondered pundits, that this particular movie is a hit at the height of the #MeToo movement? Why are women flocking to see a film about a rich, white man dominating a much younger, much less powerful woman? In a squalid, lawless “fugee” camp (the letters R and e have fallen off the entrance gate) that looks and smells like a giant Portaloo, one of the characters in Mohammed Hanif’s ambitious third novel considers running away to the desert. “What’s the worst that can happen,” he thinks. “I’ll starve to death. I’ll roast under the sun. God left this place a long time ago… He had had enough. I have had a bit more than that.” This philosophical passage is spoken by a dog called Mutt, and Hanif’s book is undoubtedly a high-wire act. Red Birds constantly threatens to fall apart, its characters and locations both achingly realistic and elusively metaphysical. But that’s part of its charm: you never know where Hanif’s farce will go next. He starts with an American pilot crashing in the desert near a downgraded refugee camp “full of human scum” he was supposed to bomb. When Major Ellie finally reaches the outskirts of the camp, Mutt introduces him to a teenage refugee named Momo, who is using an old copy of Fortune as his guide to becoming a hotshot businessman.

In a squalid, lawless “fugee” camp (the letters R and e have fallen off the entrance gate) that looks and smells like a giant Portaloo, one of the characters in Mohammed Hanif’s ambitious third novel considers running away to the desert. “What’s the worst that can happen,” he thinks. “I’ll starve to death. I’ll roast under the sun. God left this place a long time ago… He had had enough. I have had a bit more than that.” This philosophical passage is spoken by a dog called Mutt, and Hanif’s book is undoubtedly a high-wire act. Red Birds constantly threatens to fall apart, its characters and locations both achingly realistic and elusively metaphysical. But that’s part of its charm: you never know where Hanif’s farce will go next. He starts with an American pilot crashing in the desert near a downgraded refugee camp “full of human scum” he was supposed to bomb. When Major Ellie finally reaches the outskirts of the camp, Mutt introduces him to a teenage refugee named Momo, who is using an old copy of Fortune as his guide to becoming a hotshot businessman. Behaviorism, which flourished in the first half of the 20th century, is a school of thought in psychology that rejects the study of conscious experience in favor of objectively measurable events (such as responses to stimuli). Due to behaviorism’s influence, researchers interested in emotion in animals have tended to take one of two approaches. Some have treated emotion as a brain state that connects external stimuli with responses.7 These researchers, for the most part, viewed such brain states as operating without the necessity of conscious awareness (and therefore as separate from feelings), thus avoiding questions about consciousness in animals.8 Others argued, in the tradition of Darwin, that humans inherited emotional states of mind from animals, and that behavioral responses give evidence that these states of mind exist in animal brains.9 The first approach has practical advantages, since it focuses research on objective responses of the body and brain, but suffers from the fact that it ignores what most people would say is the essence of an emotion: the conscious feeling. The second approach puts feelings front and center, but is based on assumptions about mental states in animals that cannot easily be verified scientifically.

Behaviorism, which flourished in the first half of the 20th century, is a school of thought in psychology that rejects the study of conscious experience in favor of objectively measurable events (such as responses to stimuli). Due to behaviorism’s influence, researchers interested in emotion in animals have tended to take one of two approaches. Some have treated emotion as a brain state that connects external stimuli with responses.7 These researchers, for the most part, viewed such brain states as operating without the necessity of conscious awareness (and therefore as separate from feelings), thus avoiding questions about consciousness in animals.8 Others argued, in the tradition of Darwin, that humans inherited emotional states of mind from animals, and that behavioral responses give evidence that these states of mind exist in animal brains.9 The first approach has practical advantages, since it focuses research on objective responses of the body and brain, but suffers from the fact that it ignores what most people would say is the essence of an emotion: the conscious feeling. The second approach puts feelings front and center, but is based on assumptions about mental states in animals that cannot easily be verified scientifically.

In 2014, two archaeologists,

In 2014, two archaeologists,  It’s no secret that computers are insecure. Stories like the

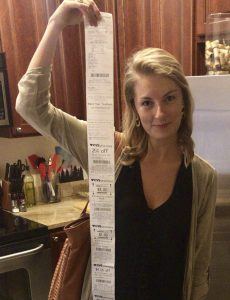

It’s no secret that computers are insecure. Stories like the  CVS is a drugstore much like other drugstores, with one important difference: The receipts are very long.

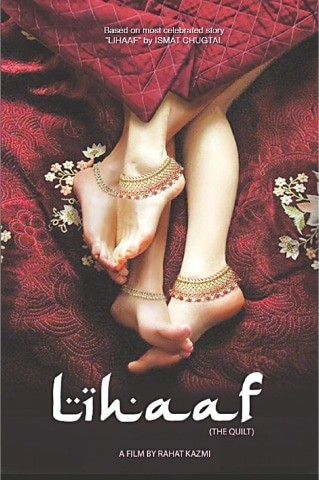

CVS is a drugstore much like other drugstores, with one important difference: The receipts are very long. A picture is worth a thousand words. In the case of Indian filmmaker (not to be confused with the Pakistani actor) Rahat Kazmi’s 2018 film Lihaaf: The Quilt, based on Ismat Chughtai’s controversial short story of the same name, the production’s publicity poster says perhaps more than a thousand words.

A picture is worth a thousand words. In the case of Indian filmmaker (not to be confused with the Pakistani actor) Rahat Kazmi’s 2018 film Lihaaf: The Quilt, based on Ismat Chughtai’s controversial short story of the same name, the production’s publicity poster says perhaps more than a thousand words.