by Carl Pierer

In the first part of this essay, the axiom of choice was introduced and a rather counterintuitive consequence was shown: the Banach-Tarski Paradox. To recapitulate: the axiom of choice states that, given any collection of non-empty sets, it is possible to choose exactly one element from each of them. This is uncontroversial in the case where the collection is finite. Simply list all the sets and then pick an element from each. Yet, as soon as we consider infinite collections, matters get more complicated. We cannot explicitly write down which element to pick, so we need to give a principled method of choosing. In some cases, this might be straightforward. For example, take an infinite collection of non-empty subsets of the natural numbers. Any such set will contain a least element. Thus, if we pick the least element from each of these sets, we have given a principled method. However, with an infinite collection of non-empty subsets of the real numbers, this particular method does not work. Moreover, there is no obvious alternative principled method. The axiom of choice then states that nonetheless such a method exists, although we do not know it. The axiom of choice entails the Banach-Tarski Paradox, which states that we can break up a ball into 8 pieces, take 4 of them, rotate them around and put them back together to get back the original ball. We can do the same thing with the remaining 4 pieces and get another ball of exactly the same size. This allows us to duplicate the ball.

The second part of this essay demonstrated a useful consequence (or indeed, an equivalent) of the axiom of choice, known as Zorn’s Lemma and looked at a few applications of this Lemma. Two positions have been mapped out in the course of this essay. On the one hand, the axiom has very counterintuitive consequences, so much so that they’ve received the name of a paradox. On the other hand, the axiom proves to be very useful in deducing mathematical propositions. These considerations lead back to the question that had already been raised at the end of the first part: how are we to decide on the status of an axiom, on whether to accept it or reject it?

In this third and final part of the essay, we will take a more philosophical approach to this problem. In particular, we will look at a possible resolution offered by Penelope Maddy in her Defending the Axioms. The solution offered would lead onto further questions about the nature of mathematics: what is mathematics actually about? At the same time, Maddy’s view is based on a certain conception of proof that does not really reflect mathematical practice. The essay, due to limitations, only hints at a different perspective offered by looking at what mathematicians actually do and what role proofs play for them. Read more »

One of the problems in discussing censorship is that we often don’t recognize censorship for what it is. There is no longer the Lord Chamberlain marking scripts and cutting out the unacceptable. Instead, we, in effect, ourselves mark them. And that, ironically, makes censorship not more, but less, visible.

One of the problems in discussing censorship is that we often don’t recognize censorship for what it is. There is no longer the Lord Chamberlain marking scripts and cutting out the unacceptable. Instead, we, in effect, ourselves mark them. And that, ironically, makes censorship not more, but less, visible. Around 558 million years ago, a strange … something dies on the floor of an ancient ocean. Its body, if you could call it that, is a two-inch-long oval with symmetric ribs running from its midline to its fringes. It is quickly buried in sediment, and gradually turns into a fossil.

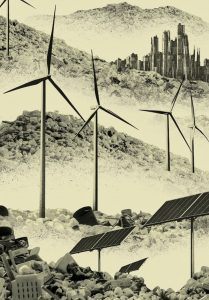

Around 558 million years ago, a strange … something dies on the floor of an ancient ocean. Its body, if you could call it that, is a two-inch-long oval with symmetric ribs running from its midline to its fringes. It is quickly buried in sediment, and gradually turns into a fossil. Warnings about ecological breakdown have become ubiquitous. Over the past few years, major newspapers, including the Guardian and the New York Times, have carried alarming stories on soil depletion, deforestation, and the collapse of fish stocks and insect populations. These crises are being driven by global economic growth, and its accompanying consumption, which is destroying the Earth’s biosphere and blowing past key planetary boundaries that scientists say must be respected to avoid triggering collapse.

Warnings about ecological breakdown have become ubiquitous. Over the past few years, major newspapers, including the Guardian and the New York Times, have carried alarming stories on soil depletion, deforestation, and the collapse of fish stocks and insect populations. These crises are being driven by global economic growth, and its accompanying consumption, which is destroying the Earth’s biosphere and blowing past key planetary boundaries that scientists say must be respected to avoid triggering collapse. It was entirely a coincidence that I found myself reading Jonathan Haidt and Greg Lukianoff’s

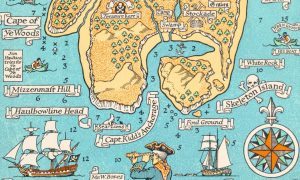

It was entirely a coincidence that I found myself reading Jonathan Haidt and Greg Lukianoff’s  I have spent much of the last few days destroying my own work. It turns out that obliterating it neatly is almost as difficult as making it. It’s publication week of my latest, The Book of Humans, and we’ve been running various competitions to draw people’s eyes in. I have great fondness for hiding secrets in my books. In one, I encoded a message in the letters of the genetic code – an email address that revealed the instructions for a treasure hunt. For The Book of Humans – surely conceived by me as an epic act of procrastination – I have dug out a hole in the middle of one copy, as if to hide a wad of cash, and inside this book-box I’ve stashed a small treasure, something mentioned in the book and of relevance to the story. So far, I’ve destroyed two practice copies with a multi-tool trying to carve and glue a neat rectangular box inside 250 pages of human evolution. I’ll push the button for this hunt to begin on Twitter this week. Let’s see how long it takes people to work out what’s in the box.

I have spent much of the last few days destroying my own work. It turns out that obliterating it neatly is almost as difficult as making it. It’s publication week of my latest, The Book of Humans, and we’ve been running various competitions to draw people’s eyes in. I have great fondness for hiding secrets in my books. In one, I encoded a message in the letters of the genetic code – an email address that revealed the instructions for a treasure hunt. For The Book of Humans – surely conceived by me as an epic act of procrastination – I have dug out a hole in the middle of one copy, as if to hide a wad of cash, and inside this book-box I’ve stashed a small treasure, something mentioned in the book and of relevance to the story. So far, I’ve destroyed two practice copies with a multi-tool trying to carve and glue a neat rectangular box inside 250 pages of human evolution. I’ll push the button for this hunt to begin on Twitter this week. Let’s see how long it takes people to work out what’s in the box. “You’re dead,” said the meditation guide. “You’ve been dead a long time.” I start crying. “What do you see?” she asked. I whimpered, “My dad somewhere, cremated, maybe a river, gone for decades. My son is older. He has a family. He thinks of me sometimes. I can’t stand it.”

“You’re dead,” said the meditation guide. “You’ve been dead a long time.” I start crying. “What do you see?” she asked. I whimpered, “My dad somewhere, cremated, maybe a river, gone for decades. My son is older. He has a family. He thinks of me sometimes. I can’t stand it.” In the beginning was the map.

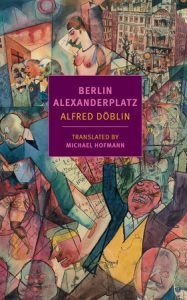

In the beginning was the map.  In the tempest-plagued teapot of English translation, Michael Hofmann’s dust-ups are notorious: he compared Stefan Zweig’s suicide note to an Oscar acceptance speech, eviscerated James Reidel’s translations of Thomas Bernhard’s poems, brushed off George Konrad’s A Feast in the Garden as “dire… export-quality horseshit.” Critics seem generally pleased with his translations, but then, critics like Toril Moi, Tim Parks, or Hofmann himself—that is to say, those willing and able to scrutinize the changes a text in translation undergoes, and the details of what is gained and lost alone the way—are rare, and the newspaper reviewer’s “cleverly translated,” “serviceably translated,” and suchlike don’t count for too much. Readers I know are not of one mind about his work: some are unqualified fans, particularly of Angina Days, his selected poetry of Günter Eich. What seems to grate on the less enthusiastic are his translations’ motley surfaces, the “occasional rhinestones or bits of jet,” as he has it in one interview, which mark them, not as the pellucid transmigration of the author’s inspiration from source language into target, but as a patent contrivance in the latter.

In the tempest-plagued teapot of English translation, Michael Hofmann’s dust-ups are notorious: he compared Stefan Zweig’s suicide note to an Oscar acceptance speech, eviscerated James Reidel’s translations of Thomas Bernhard’s poems, brushed off George Konrad’s A Feast in the Garden as “dire… export-quality horseshit.” Critics seem generally pleased with his translations, but then, critics like Toril Moi, Tim Parks, or Hofmann himself—that is to say, those willing and able to scrutinize the changes a text in translation undergoes, and the details of what is gained and lost alone the way—are rare, and the newspaper reviewer’s “cleverly translated,” “serviceably translated,” and suchlike don’t count for too much. Readers I know are not of one mind about his work: some are unqualified fans, particularly of Angina Days, his selected poetry of Günter Eich. What seems to grate on the less enthusiastic are his translations’ motley surfaces, the “occasional rhinestones or bits of jet,” as he has it in one interview, which mark them, not as the pellucid transmigration of the author’s inspiration from source language into target, but as a patent contrivance in the latter. “The trouble with life (the novelist will feel) is its amorphousness, its ridiculous fluidity,” writes Martin Amis in his memoir Experience. “Look at it: thinly plotted, largely themeless, sentimental and ineluctably trite. The dialogue is poor, or at least violently uneven. The twists are predictable or sensationalist. And it’s always the same beginning; and the same ending…”

“The trouble with life (the novelist will feel) is its amorphousness, its ridiculous fluidity,” writes Martin Amis in his memoir Experience. “Look at it: thinly plotted, largely themeless, sentimental and ineluctably trite. The dialogue is poor, or at least violently uneven. The twists are predictable or sensationalist. And it’s always the same beginning; and the same ending…”

I can make a

I can make a  I met

I met  Homi Bhabha:

Homi Bhabha: