Helen Macdonald in The Atlantic:

I can make a passable imitation of a raven’s low, guttural croak, and whenever I see a wild one flying overhead I have an irresistible urge to call up to it in the hope that it will answer back. Sometimes I do, and sometimes it does; it’s a moment of cross-species communication that never fails to thrill. Ravens are strangely magical birds. Partly that magic is made by us. They have been seen variously as gods, tricksters, protectors, messengers, and harbingers of death for thousands of years. But much of that magic emanates from the living birds themselves. Massive black corvids with ice-pick beaks, dark eyes, and shaggy-feathered necks, they have a distinctive presence and possess a fierce intelligence. Watching them for any length of time has the same effect as watching great apes: It’s hard not to start thinking of them as people. Nonhuman people, but people all the same.

I can make a passable imitation of a raven’s low, guttural croak, and whenever I see a wild one flying overhead I have an irresistible urge to call up to it in the hope that it will answer back. Sometimes I do, and sometimes it does; it’s a moment of cross-species communication that never fails to thrill. Ravens are strangely magical birds. Partly that magic is made by us. They have been seen variously as gods, tricksters, protectors, messengers, and harbingers of death for thousands of years. But much of that magic emanates from the living birds themselves. Massive black corvids with ice-pick beaks, dark eyes, and shaggy-feathered necks, they have a distinctive presence and possess a fierce intelligence. Watching them for any length of time has the same effect as watching great apes: It’s hard not to start thinking of them as people. Nonhuman people, but people all the same.

The most celebrated ravens in the world live at the Tower of London, on the River Thames, an 11th-century walled enclosure of towers and buildings that houses the Crown Jewels and that over the ages has functioned as a royal palace, a zoo, a prison, and a place of execution. Today it is one of Britain’s most visited tourist attractions, and its ravens amble across its greens entirely unbothered by the crowds, walking with a gait that Charles Dickens—who kept ravens—described as resembling “a very particular gentleman with exceedingly tight boots on, trying to walk fast over loose pebbles.”

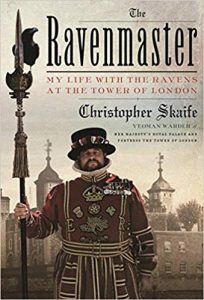

I met Christopher Skaife a few years ago while recording a radio program about Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven.” A jovial, bearded man, he’s one of the yeoman warders at the Tower of London. As such he is a member of an ancient and soldierly profession. For the past 13 years he has also been the site’s ravenmaster, which easily tops my list of favorite job titles (unicef’s “head of knowledge” comes in second). On Twitter, as @Ravenmaster1, he curates a much-loved feed packed with images of the birds in his care: raven beaks holding information leaflets, photos of the feathers on their broad backs, close-ups of their varied expressions, videos of their gentle interactions with him. A born storyteller with a gift for banter honed by years in the British army, Skaife has written a book that is far from a dry monograph about the species or a sentimental love letter to his birds.

I met Christopher Skaife a few years ago while recording a radio program about Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven.” A jovial, bearded man, he’s one of the yeoman warders at the Tower of London. As such he is a member of an ancient and soldierly profession. For the past 13 years he has also been the site’s ravenmaster, which easily tops my list of favorite job titles (unicef’s “head of knowledge” comes in second). On Twitter, as @Ravenmaster1, he curates a much-loved feed packed with images of the birds in his care: raven beaks holding information leaflets, photos of the feathers on their broad backs, close-ups of their varied expressions, videos of their gentle interactions with him. A born storyteller with a gift for banter honed by years in the British army, Skaife has written a book that is far from a dry monograph about the species or a sentimental love letter to his birds.

More here.