Gretchen McCullough at The Millions:

One of the pleasures of reading critic and fiction writer Yahya Haqqi’s essays in Arabic is that I am always astonished by the breadth of his knowledge, the depth of his experience, the nimbleness of his mind and his eloquence. In the collection Crying, Then Smiling, he has a number of eulogies, one of which is for his uncle, Mahmoud Taher Haqqi, who wrote the first Egyptian novel, The Maidens of Denshawi, about the tragedy of Denshawi in 1906 where British soldiers carelessly killed a villager while they were shooting pigeons—the incident ended tragically when villagers were rounded up and executed by the British. Haqqi points out that it was the first novel to focus on fellaheen, peasants, and their problems and opened the way for Mohamed Hussein Haykal’s novel, Zeyneb (1913). Haqqi wrote that his heart trembled when he read The Maidens of Denshawi—which is what good stories should bring about. Haqqi deserves a eulogy, much like the ones he so generously wrote for others, about his place in Egyptian literary heritage. This seems appropriate in light of the recent celebration of the classic black and white film Al-Bostagy, or The Postman, directed by Husayn Kamal (1968), featuring Shukry Sarhan, based on Haqqi’s novella. But one cannot write about this poignant film without mentioning Sabri Moussa, the talented novelist who translated the spirit of Yahya Haqqi’s novella into a suspenseful screenplay. (He also wrote the screenplay for Yahya Haqqi’s Om Hashem’s Lamp.) Sabri Moussa, who died recently, January 2018, deserves a eulogy as well for his film scripts, short fiction, and novels—the unusual sci-fi tale The Man Arrived from the Spinach Field, the mythic fable Seeds of Corruption, and Half-Meter Incident.

One of the pleasures of reading critic and fiction writer Yahya Haqqi’s essays in Arabic is that I am always astonished by the breadth of his knowledge, the depth of his experience, the nimbleness of his mind and his eloquence. In the collection Crying, Then Smiling, he has a number of eulogies, one of which is for his uncle, Mahmoud Taher Haqqi, who wrote the first Egyptian novel, The Maidens of Denshawi, about the tragedy of Denshawi in 1906 where British soldiers carelessly killed a villager while they were shooting pigeons—the incident ended tragically when villagers were rounded up and executed by the British. Haqqi points out that it was the first novel to focus on fellaheen, peasants, and their problems and opened the way for Mohamed Hussein Haykal’s novel, Zeyneb (1913). Haqqi wrote that his heart trembled when he read The Maidens of Denshawi—which is what good stories should bring about. Haqqi deserves a eulogy, much like the ones he so generously wrote for others, about his place in Egyptian literary heritage. This seems appropriate in light of the recent celebration of the classic black and white film Al-Bostagy, or The Postman, directed by Husayn Kamal (1968), featuring Shukry Sarhan, based on Haqqi’s novella. But one cannot write about this poignant film without mentioning Sabri Moussa, the talented novelist who translated the spirit of Yahya Haqqi’s novella into a suspenseful screenplay. (He also wrote the screenplay for Yahya Haqqi’s Om Hashem’s Lamp.) Sabri Moussa, who died recently, January 2018, deserves a eulogy as well for his film scripts, short fiction, and novels—the unusual sci-fi tale The Man Arrived from the Spinach Field, the mythic fable Seeds of Corruption, and Half-Meter Incident.

more here.

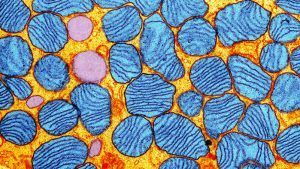

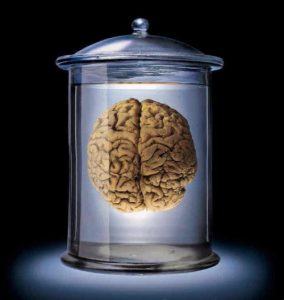

The human gut is lined with more than 100 million nerve cells—it’s practically a brain unto itself. And indeed, the gut actually talks to the brain, releasing hormones into the bloodstream that, over the course of about 10 minutes, tell us how hungry it is, or that we shouldn’t have eaten an entire pizza. But a new study reveals the gut has a much more direct connection to the brain through a neural circuit that allows it to transmit signals in mere seconds. The findings could lead to new treatments for obesity, eating disorders, and even depression and autism—all of which have been linked to a malfunctioning gut. The study reveals “a new set of pathways that use gut cells to rapidly communicate with … the brain stem,” says Daniel Drucker, a clinician-scientist who studies gut disorders at the Lunenfeld-Tanenbaum Research Institute in Toronto, Canada, who was not involved with the work. Although many questions remain before the clinical implications become clear, he says, “This is a cool new piece of the puzzle.”

The human gut is lined with more than 100 million nerve cells—it’s practically a brain unto itself. And indeed, the gut actually talks to the brain, releasing hormones into the bloodstream that, over the course of about 10 minutes, tell us how hungry it is, or that we shouldn’t have eaten an entire pizza. But a new study reveals the gut has a much more direct connection to the brain through a neural circuit that allows it to transmit signals in mere seconds. The findings could lead to new treatments for obesity, eating disorders, and even depression and autism—all of which have been linked to a malfunctioning gut. The study reveals “a new set of pathways that use gut cells to rapidly communicate with … the brain stem,” says Daniel Drucker, a clinician-scientist who studies gut disorders at the Lunenfeld-Tanenbaum Research Institute in Toronto, Canada, who was not involved with the work. Although many questions remain before the clinical implications become clear, he says, “This is a cool new piece of the puzzle.” Spike Lee

Spike Lee Stephen Hawking sadly

Stephen Hawking sadly  The word “Chinko” means nothing. It is the name given to a river in a place where the river gets lost in thick brush and fields of termite mounds. Chinko Park, established to protect what little is left, is called a national park, but there is nothing national in a place without the rule of law. Chinko’s only defense is a handful of well-trained rangers who spend weeks at a time in the wild, waiting for poachers or armed groups to emerge from the thick bush and attack. This is a dangerous part of the world—everyone knows at least that much.

The word “Chinko” means nothing. It is the name given to a river in a place where the river gets lost in thick brush and fields of termite mounds. Chinko Park, established to protect what little is left, is called a national park, but there is nothing national in a place without the rule of law. Chinko’s only defense is a handful of well-trained rangers who spend weeks at a time in the wild, waiting for poachers or armed groups to emerge from the thick bush and attack. This is a dangerous part of the world—everyone knows at least that much. On December 31,

On December 31,  The

The Alejandro Escovedo, the singer and songwriter, likes to have a proper Mexican breakfast before a long drive. “Let’s go here,” he said. He pulled into the back lot of a restaurant called El Pueblo, across from the Tornado bus terminal on East Jefferson Boulevard, in the Oak Cliff section of Dallas. El Pueblo, he said, is where travellers arriving by bus from Mexico often go to eat and to get their bearings. He ordered in Spanish, then remarked that his Spanish was poor. The plates came quickly. Chorizo con huevos. “This is bad_ass_, man,” he said. An elderly vagrant looked in through the window and then walked in. Escovedo gave him a dollar. “When I was small, I used to be able to see the pain in people,” he said.

Alejandro Escovedo, the singer and songwriter, likes to have a proper Mexican breakfast before a long drive. “Let’s go here,” he said. He pulled into the back lot of a restaurant called El Pueblo, across from the Tornado bus terminal on East Jefferson Boulevard, in the Oak Cliff section of Dallas. El Pueblo, he said, is where travellers arriving by bus from Mexico often go to eat and to get their bearings. He ordered in Spanish, then remarked that his Spanish was poor. The plates came quickly. Chorizo con huevos. “This is bad_ass_, man,” he said. An elderly vagrant looked in through the window and then walked in. Escovedo gave him a dollar. “When I was small, I used to be able to see the pain in people,” he said. When I was 11, I read Little

When I was 11, I read Little

Recently, CNN sent their reporter to cover yet another Trump rally (in Pennsylvania), but this time reporter Gary Tuchman was assigned the more specific task of interviewing Trump supporters who were carrying signs or large cardboard cut-outs of the letter “Q” and wearing T-shirts proclaiming “We are Q”.

Recently, CNN sent their reporter to cover yet another Trump rally (in Pennsylvania), but this time reporter Gary Tuchman was assigned the more specific task of interviewing Trump supporters who were carrying signs or large cardboard cut-outs of the letter “Q” and wearing T-shirts proclaiming “We are Q”. In the 1960s, in the sleepy little city of Sialkot, almost in no-man’s land between India and Pakistan and of little significance except for its large cantonment and its factories of surgical instruments and sports goods, there were two cinema houses, all within a mile of our house, No. 3 Kutchery Road. Well three to be exact, the third being an improvisation involving two tree trunks with a white sheet slung between them at the Services club and only on Saturday nights.

In the 1960s, in the sleepy little city of Sialkot, almost in no-man’s land between India and Pakistan and of little significance except for its large cantonment and its factories of surgical instruments and sports goods, there were two cinema houses, all within a mile of our house, No. 3 Kutchery Road. Well three to be exact, the third being an improvisation involving two tree trunks with a white sheet slung between them at the Services club and only on Saturday nights. Would I rather go deaf or blind? Every once in a while, I come back to this question in some version or another. Say I had to choose which sense I’d lose in my old age, which would it be? I always give myself, unequivocally, the same answer: I’d rather go blind. I’d rather my world go darker than quieter. I imagine it as a choice between seeing the world and communicating with it; in this hypothetical, communication with the world is all-encompassing, its loss more devastating than the loss of sight. It is perhaps clear from the mere fact that I pose this question that I do not live with a disability involving the senses. Individuals who are vision- or hearing-impaired would have an entirely different take on this question and on the issues I raise below, but hopefully what I write here will go beyond stating my own prejudices.

Would I rather go deaf or blind? Every once in a while, I come back to this question in some version or another. Say I had to choose which sense I’d lose in my old age, which would it be? I always give myself, unequivocally, the same answer: I’d rather go blind. I’d rather my world go darker than quieter. I imagine it as a choice between seeing the world and communicating with it; in this hypothetical, communication with the world is all-encompassing, its loss more devastating than the loss of sight. It is perhaps clear from the mere fact that I pose this question that I do not live with a disability involving the senses. Individuals who are vision- or hearing-impaired would have an entirely different take on this question and on the issues I raise below, but hopefully what I write here will go beyond stating my own prejudices. The idea of ‘good corporate citizenship’ has become popular recently among business ethicists and corporate leaders. You may have noticed its appearance on corporate websites and CEO speeches. But what does it mean and does it matter? Is it any more than a new species of public relations flimflam to set beside terms like ‘corporate social responsibility’ and the ‘triple bottom line’? Is it just a metaphor?

The idea of ‘good corporate citizenship’ has become popular recently among business ethicists and corporate leaders. You may have noticed its appearance on corporate websites and CEO speeches. But what does it mean and does it matter? Is it any more than a new species of public relations flimflam to set beside terms like ‘corporate social responsibility’ and the ‘triple bottom line’? Is it just a metaphor? Learning Objectives. Measurable Outcomes. These are among the buzziest of buzz words in current debates about education. And that discordant groaning noise you can hear around many academic departments is the sound of recalcitrant faculty, following orders from on high, unenthusiastically inserting learning objectives (henceforth LOs) and measurable outcomes (hereafter MOs) into already bloated syllabi or program assessment instruments.

Learning Objectives. Measurable Outcomes. These are among the buzziest of buzz words in current debates about education. And that discordant groaning noise you can hear around many academic departments is the sound of recalcitrant faculty, following orders from on high, unenthusiastically inserting learning objectives (henceforth LOs) and measurable outcomes (hereafter MOs) into already bloated syllabi or program assessment instruments.