Emily Conover in Science News:

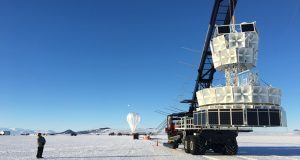

Dangling from a balloon high above Antarctica, a particle detector has spotted something that standard physics is at a loss to explain.

Dangling from a balloon high above Antarctica, a particle detector has spotted something that standard physics is at a loss to explain.

Two unusual signals seen by the detector, known as the Antarctic Impulsive Transient Antenna, or ANITA, can’t be attributed to any known particles, a team of physicists at Penn State reports online September 25 at arXiv.org. The result hints at the possibility of new particles beyond those cataloged in the standard model, the theory that describes the various elementary particles that make up matter.

Like the old man in the Pixar movie Up, ANITA floats on a helium balloon, at an altitude of 37 kilometers for about a month at a time. It searches for the signals of high-energy particles from space, including lightweight, ghostly particles called neutrinos. Those neutrinos can interact within Antarctica’s ice, producing radio waves that are picked up by ANITA’s antennas.

The two puzzling signals appear to be from extremely energetic neutrinos shooting skyward from within the Earth. A neutrino coming up from below isn’t inherently surprising: Low-energy neutrinos interact with matter so weakly that they can zip through the entire planet. But high-energy neutrinos can’t pass through as much material as lower-energy neutrinos can. So although high-energy neutrinos can skim the edges of the planet, they won’t survive a pass straight through.

More here.

The cries of “Shame! Shame! Shame!” rang throughout the marbled walls of the

The cries of “Shame! Shame! Shame!” rang throughout the marbled walls of the  The man was 23 when the delusions came on. He became convinced that his thoughts were leaking out of his head and that other people could hear them. When he watched television, he thought the actors were signaling him, trying to communicate. He became irritable and anxious and couldn’t sleep. Dr. Tsuyoshi Miyaoka, a psychiatrist treating him at the Shimane University School of Medicine in Japan, eventually diagnosed paranoid schizophrenia. He then prescribed a series of antipsychotic drugs. None helped. The man’s symptoms were, in medical parlance, “treatment resistant.” A year later,

The man was 23 when the delusions came on. He became convinced that his thoughts were leaking out of his head and that other people could hear them. When he watched television, he thought the actors were signaling him, trying to communicate. He became irritable and anxious and couldn’t sleep. Dr. Tsuyoshi Miyaoka, a psychiatrist treating him at the Shimane University School of Medicine in Japan, eventually diagnosed paranoid schizophrenia. He then prescribed a series of antipsychotic drugs. None helped. The man’s symptoms were, in medical parlance, “treatment resistant.” A year later,

Before 2016 Jordan Peterson was indistinguishable from any other relatively successful academic with a respectable scholarly pedigree: B.A. in political science from the University of Alberta (1982), B.A. in psychology from the same institution (1984), Ph.D. in clinical psychology from McGill University (1991), postdoc at McGill’s Douglas Hospital (1992–1993), assistant and associate professorships at Harvard University in the psychology department (1993–1998), full tenured professorship at the University of Toronto (1999 to present), private clinical practice in Toronto, and a scholarly book by a reputable publishing house (Routledge). This ordinary career path turned extraordinary in 2016 when the controversial Bill C-16, a federal amendment to the Canadian Human Rights Act and Criminal Code, was passed, “to protect individuals from discrimination within the sphere of federal jurisdiction and from being the targets of hate propaganda, as a consequence of their gender identity or their gender expression.”

Before 2016 Jordan Peterson was indistinguishable from any other relatively successful academic with a respectable scholarly pedigree: B.A. in political science from the University of Alberta (1982), B.A. in psychology from the same institution (1984), Ph.D. in clinical psychology from McGill University (1991), postdoc at McGill’s Douglas Hospital (1992–1993), assistant and associate professorships at Harvard University in the psychology department (1993–1998), full tenured professorship at the University of Toronto (1999 to present), private clinical practice in Toronto, and a scholarly book by a reputable publishing house (Routledge). This ordinary career path turned extraordinary in 2016 when the controversial Bill C-16, a federal amendment to the Canadian Human Rights Act and Criminal Code, was passed, “to protect individuals from discrimination within the sphere of federal jurisdiction and from being the targets of hate propaganda, as a consequence of their gender identity or their gender expression.” In 1921, 24-year-old William Faulkner had dropped out of the University of Mississippi (for the second time) and was living in Greenwich Village, working in a bookstore—but he was getting restless. Eventually, his mentor, Phil Stone, an Oxford attorney, arranged for him to be appointed postmaster at the school he had only recently left. He was paid a salary of $1,700 in 1922 and $1,800 in the following years, but it’s unclear how he came by that raise, because by all accounts he was uniquely terrible at his job. “I forced Bill to take the job over his own declination and refusal,” Stone said later, according to David Minter’s biography. “He made the damndest postmaster the world has ever seen.”

In 1921, 24-year-old William Faulkner had dropped out of the University of Mississippi (for the second time) and was living in Greenwich Village, working in a bookstore—but he was getting restless. Eventually, his mentor, Phil Stone, an Oxford attorney, arranged for him to be appointed postmaster at the school he had only recently left. He was paid a salary of $1,700 in 1922 and $1,800 in the following years, but it’s unclear how he came by that raise, because by all accounts he was uniquely terrible at his job. “I forced Bill to take the job over his own declination and refusal,” Stone said later, according to David Minter’s biography. “He made the damndest postmaster the world has ever seen.” When René Descartes was 31 years old, in 1627, he began to write a manifesto on the proper methods of philosophising. He chose the title Regulae ad Directionem Ingenii, or Rules for the Direction of the Mind. It is a curious work. Descartes originally intended to present 36 rules divided evenly into three parts, but the manuscript trails off in the middle of the second part. Each rule was to be set forth in one or two sentences followed by a lengthy elaboration. The first rule tells us that ‘The end of study should be to direct the mind to an enunciation of sound and correct judgments on all matters that come before it,’ and the third rule tells us that ‘Our enquiries should be directed, not to what others have thought … but to what we can clearly and perspicuously behold and with certainty deduce.’ Rule four tells us that ‘There is a need of a method for finding out the truth.’

When René Descartes was 31 years old, in 1627, he began to write a manifesto on the proper methods of philosophising. He chose the title Regulae ad Directionem Ingenii, or Rules for the Direction of the Mind. It is a curious work. Descartes originally intended to present 36 rules divided evenly into three parts, but the manuscript trails off in the middle of the second part. Each rule was to be set forth in one or two sentences followed by a lengthy elaboration. The first rule tells us that ‘The end of study should be to direct the mind to an enunciation of sound and correct judgments on all matters that come before it,’ and the third rule tells us that ‘Our enquiries should be directed, not to what others have thought … but to what we can clearly and perspicuously behold and with certainty deduce.’ Rule four tells us that ‘There is a need of a method for finding out the truth.’

Emmy Noether was a force in mathematics — and knew it. She was fully confident in her capabilities and ideas. Yet a century on, those ideas, and their contribution to science, often go unnoticed. Most physicists are aware of her fundamental theorem, which puts symmetry at the heart of physical law. But how many know anything of her and her life?

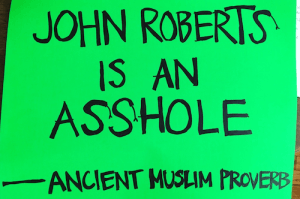

Emmy Noether was a force in mathematics — and knew it. She was fully confident in her capabilities and ideas. Yet a century on, those ideas, and their contribution to science, often go unnoticed. Most physicists are aware of her fundamental theorem, which puts symmetry at the heart of physical law. But how many know anything of her and her life? When last June we heard about the kids arriving in New York from the Southern border—the first moment the child separation policy flared into the public eye, the first I knew of its systematic existence—we raced to LaGuardia to witness, to support, to stage something visible, at least. We made posters on the M60 bus. I passed around fat sharpies, brought extra neon poster-board. No one knew what to write, or who to address. The children? Their captors? The news cameras? It maybe wasn’t a great decision. The couple of kids I saw filing out of side doors were so little and tired and quiet. I’m not sure a phalanx of screaming adults helped, though it gave the TV cameras something to show other than their tiny bodies. Some stubborn questioners managed to get information about where the children were being taken in the unmarked vans.

When last June we heard about the kids arriving in New York from the Southern border—the first moment the child separation policy flared into the public eye, the first I knew of its systematic existence—we raced to LaGuardia to witness, to support, to stage something visible, at least. We made posters on the M60 bus. I passed around fat sharpies, brought extra neon poster-board. No one knew what to write, or who to address. The children? Their captors? The news cameras? It maybe wasn’t a great decision. The couple of kids I saw filing out of side doors were so little and tired and quiet. I’m not sure a phalanx of screaming adults helped, though it gave the TV cameras something to show other than their tiny bodies. Some stubborn questioners managed to get information about where the children were being taken in the unmarked vans. Cicadas might be a pest, but they’re special in a few respects. For one, these droning insects have a habit of emerging after a prime number of years (7, 13, or 17). They also feed exclusively on plant sap, which is strikingly low in nutrients. To make up for this deficiency, cicadas depend on two different strains of bacteria that they keep cloistered within special cells, and that provide them with additional amino acids. All three partners – the cicadas and the two types of microbes – have evolved in concert, and none could survive on its own. These organisms together make up what’s

Cicadas might be a pest, but they’re special in a few respects. For one, these droning insects have a habit of emerging after a prime number of years (7, 13, or 17). They also feed exclusively on plant sap, which is strikingly low in nutrients. To make up for this deficiency, cicadas depend on two different strains of bacteria that they keep cloistered within special cells, and that provide them with additional amino acids. All three partners – the cicadas and the two types of microbes – have evolved in concert, and none could survive on its own. These organisms together make up what’s  “Look at me when I’m talking to you! You’re telling me that my assault doesn’t matter. That what happened to me doesn’t matter!” Those anguished words came from Maria Gallagher, who, along with Ana Maria Archila,

“Look at me when I’m talking to you! You’re telling me that my assault doesn’t matter. That what happened to me doesn’t matter!” Those anguished words came from Maria Gallagher, who, along with Ana Maria Archila,  In 2016, Russian born novelist Gary Shteyngart took a bus ride. It was an uncertain time in American culture and politics, and Shteyngart, who’s won a devoted following for his bestsellers “Absurdistan, “Super Sad True Love Story” and the memoir “Little Failure,” didn’t know what would come of the journey. Two years later, he’s emerged with not just the first big novel of the post-Obama era, but the first truly great novel of it.

In 2016, Russian born novelist Gary Shteyngart took a bus ride. It was an uncertain time in American culture and politics, and Shteyngart, who’s won a devoted following for his bestsellers “Absurdistan, “Super Sad True Love Story” and the memoir “Little Failure,” didn’t know what would come of the journey. Two years later, he’s emerged with not just the first big novel of the post-Obama era, but the first truly great novel of it. Transhumanism (also abbreviated as H+) is a philosophical movement which advocates for technology not only enhancing human life, but to take over human life by merging human and machine. The idea is that in one future day, humans will be vastly more intelligent, healthy, and physically powerful. In fact, much of this movement is based upon the notion that death is not an option with a focus to improve the somatic body and make humans immortal.

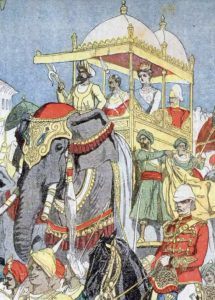

Transhumanism (also abbreviated as H+) is a philosophical movement which advocates for technology not only enhancing human life, but to take over human life by merging human and machine. The idea is that in one future day, humans will be vastly more intelligent, healthy, and physically powerful. In fact, much of this movement is based upon the notion that death is not an option with a focus to improve the somatic body and make humans immortal. On 24 September 1599, while William Shakespeare was mulling over a draft of Hamlet in his house downriver from the Globe in Southwark, a mile to the north a motley group of Londoners were gathering in a half-timbered Tudor hall. The men had come together to petition the ageing Elizabeth I, then a bewigged and painted sexagenarian, to start up a company “to venter in a voiage to ye Est Indies”.

On 24 September 1599, while William Shakespeare was mulling over a draft of Hamlet in his house downriver from the Globe in Southwark, a mile to the north a motley group of Londoners were gathering in a half-timbered Tudor hall. The men had come together to petition the ageing Elizabeth I, then a bewigged and painted sexagenarian, to start up a company “to venter in a voiage to ye Est Indies”. In “Duende” and in her third book, the Pulitzer Prize-winning “

In “Duende” and in her third book, the Pulitzer Prize-winning “