Jocelyn Kaiser in Science:

When molecular biologist Darren Baker was winding up his postdoc studying cancer and aging a few years ago at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, he faced dispiritingly low odds of winning a National Cancer Institute grant to launch his own lab. A seemingly unlikely area, however, beckoned: Alzheimer’s disease. The U.S. government had begun to ramp up research spending on the neurodegenerative condition, which is the sixth-leading cause of death in the United States and will afflict an estimated 14 million people in this country by 2050. “There was an incentive to do some exploratory work,” Baker recalls.

When molecular biologist Darren Baker was winding up his postdoc studying cancer and aging a few years ago at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, he faced dispiritingly low odds of winning a National Cancer Institute grant to launch his own lab. A seemingly unlikely area, however, beckoned: Alzheimer’s disease. The U.S. government had begun to ramp up research spending on the neurodegenerative condition, which is the sixth-leading cause of death in the United States and will afflict an estimated 14 million people in this country by 2050. “There was an incentive to do some exploratory work,” Baker recalls.

Baker’s postdoc studies had focused on cellular senescence, the cellular version of aging, which had not yet been linked to Alzheimer’s. But when he gave a drug that kills senescent cells to mice genetically engineered to develop an Alzheimer’s-like illness, the animals suffered less memory loss and fewer of the brain changes that are hallmarks of the disease. Last year, those data helped Baker win his first independent National Institutes of Health (NIH) research grant—not from NIH’s National Cancer Institute, which he once expected to rely on, but from the National Institute on Aging (NIA) in Bethesda, Maryland. He now has a six-person lab at the Mayo Clinic, working on senescence and Alzheimer’s.

Baker is the kind of newcomer NIH hoped to attract with its recent Alzheimer’s funding bonanza. For years, patient advocates have pointed to the growing toll and burgeoning costs of Alzheimer’s as the U.S. population ages. Spurred by those projections and a controversial national goal to effectively treat the disease by 2025, Congress has over 3 years tripled NIH’s annual budget for Alzheimer’s and related dementias, to $1.9 billion. The growth spurt isn’t over: Two draft 2019 spending bills for NIH would bring the total to $2.3 billion—more than 5% of NIH’s overall budget.

More here.

The

The  It takes Deborah Eisenberg about a year to write a short story. She works at a desk overlooking the gently curving stairwell in her spacious, light-soaked Chelsea apartment. A small painting of a brick wall, suspended from the high ceiling by two slender cables, hangs at eye level in front of the desk, a sardonic reminder of the nature of her task. For Eisenberg, coming up against a brick wall is what writing often feels like. At 72, she has been conducting her siege on the ineffable for more than four decades, and yet the creative process remains almost totally opaque to her. “You work and you work and you work and you work,” she told me recently, her delicate, quavering voice an audible testament to the endless hours of labor. “And for months or years on end, you’re just a total dray horse, and then you finally finish something, and the next day you look at it and you think, How did that get there? What is that? Why were those the things that I seemed to need to say?”

It takes Deborah Eisenberg about a year to write a short story. She works at a desk overlooking the gently curving stairwell in her spacious, light-soaked Chelsea apartment. A small painting of a brick wall, suspended from the high ceiling by two slender cables, hangs at eye level in front of the desk, a sardonic reminder of the nature of her task. For Eisenberg, coming up against a brick wall is what writing often feels like. At 72, she has been conducting her siege on the ineffable for more than four decades, and yet the creative process remains almost totally opaque to her. “You work and you work and you work and you work,” she told me recently, her delicate, quavering voice an audible testament to the endless hours of labor. “And for months or years on end, you’re just a total dray horse, and then you finally finish something, and the next day you look at it and you think, How did that get there? What is that? Why were those the things that I seemed to need to say?” Prisons are reminiscent of Tolstoy’s famous observation about unhappy families: Each “is unhappy in its own way,” though there are some common features — for prisons, the grim and stifling recognition that someone else has total authority over your life.

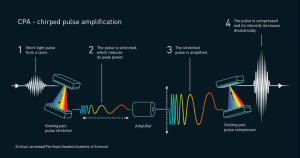

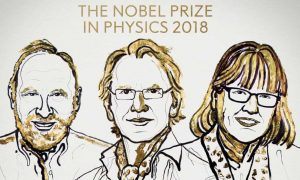

Prisons are reminiscent of Tolstoy’s famous observation about unhappy families: Each “is unhappy in its own way,” though there are some common features — for prisons, the grim and stifling recognition that someone else has total authority over your life. Three scientists have been awarded the 2018 Nobel prize in physics for creating groundbreaking tools from beams of light.

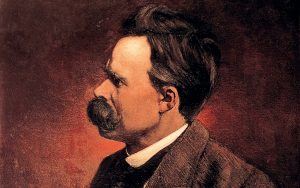

Three scientists have been awarded the 2018 Nobel prize in physics for creating groundbreaking tools from beams of light. The Nietzsche scholar Walter Kaufmann told a story of how, in 1952, just two years after publishing his ground-breaking book, Nietzsche: Philosopher, Psychologist, Antichrist, he visited the Cambridge philosopher CD Broad at Trinity College. During their conversation, Broad mentioned someone by the name of Salter. Was that, Kaufmann asked, the Salter who had written a book on Nietzsche? “Dear no,” Broad replied, “he did not deal with crackpot subjects like that; he wrote about psychical research.” In the years immediately before, during and just after the Second World War, Nietzsche’s reputation in the English-speaking world was at its lowest, largely owing to the fact that his work had been, with the support of his virulently anti-Semitic sister Elisabeth, appropriated by the Nazis. In their hands, Nietzsche’s notion of the Übermensch (I prefer to use the original German than any of the published translations; “superman” sounds silly, and “beyond-man” and “overman” do not sound like natural English) became associated with notions of Aryan racial superiority, while his idea of the “will to power” was used to justify militarism and authoritarianism.

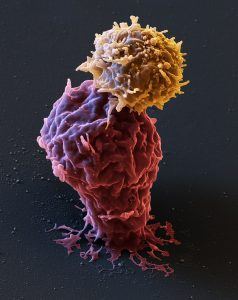

The Nietzsche scholar Walter Kaufmann told a story of how, in 1952, just two years after publishing his ground-breaking book, Nietzsche: Philosopher, Psychologist, Antichrist, he visited the Cambridge philosopher CD Broad at Trinity College. During their conversation, Broad mentioned someone by the name of Salter. Was that, Kaufmann asked, the Salter who had written a book on Nietzsche? “Dear no,” Broad replied, “he did not deal with crackpot subjects like that; he wrote about psychical research.” In the years immediately before, during and just after the Second World War, Nietzsche’s reputation in the English-speaking world was at its lowest, largely owing to the fact that his work had been, with the support of his virulently anti-Semitic sister Elisabeth, appropriated by the Nazis. In their hands, Nietzsche’s notion of the Übermensch (I prefer to use the original German than any of the published translations; “superman” sounds silly, and “beyond-man” and “overman” do not sound like natural English) became associated with notions of Aryan racial superiority, while his idea of the “will to power” was used to justify militarism and authoritarianism. A highly unusual death has exposed a weak spot in a groundbreaking cancer treatment: One rogue cell, genetically altered by the therapy, can spiral out of control in a patient and cause a fatal relapse. The treatment, a form of immunotherapy, genetically engineers a patient’s own white blood cells to fight cancer. Sometimes described as a “living drug,” it has brought lasting remissions to leukemia patients who were on the brink of death. Among them is Emily Whitehead, the first child to receive the treatment, in 2012 when she was 6. The treatment does not always work, and side effects can be dangerous, even life-threatening. Doctors have learned to manage them. But in one patient, the therapy seems to have backfired in a previously unknown way. He was 20, with an aggressive type of leukemia. The treatment altered not just his cancer-fighting cells, but also — inadvertently — the genes of one leukemia cell. The genetic change made that cell invisible to the ones that had been programmed to seek and destroy cancer.

A highly unusual death has exposed a weak spot in a groundbreaking cancer treatment: One rogue cell, genetically altered by the therapy, can spiral out of control in a patient and cause a fatal relapse. The treatment, a form of immunotherapy, genetically engineers a patient’s own white blood cells to fight cancer. Sometimes described as a “living drug,” it has brought lasting remissions to leukemia patients who were on the brink of death. Among them is Emily Whitehead, the first child to receive the treatment, in 2012 when she was 6. The treatment does not always work, and side effects can be dangerous, even life-threatening. Doctors have learned to manage them. But in one patient, the therapy seems to have backfired in a previously unknown way. He was 20, with an aggressive type of leukemia. The treatment altered not just his cancer-fighting cells, but also — inadvertently — the genes of one leukemia cell. The genetic change made that cell invisible to the ones that had been programmed to seek and destroy cancer.

Every October there’s a huge book fair in my town, where used books donated by the community are put up for sale in a large hall at the fairgrounds. It’s no exaggeration to say that it’s a high point of my year.

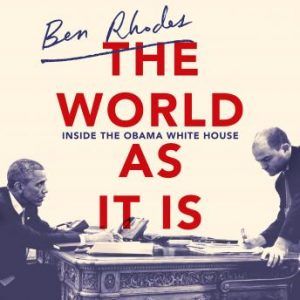

Every October there’s a huge book fair in my town, where used books donated by the community are put up for sale in a large hall at the fairgrounds. It’s no exaggeration to say that it’s a high point of my year. As the first African American president of the United States (US), Barack Obama is a uniquely historical personality. Each of us has our opinions, or will formulate opinions, as to the success or limitations of his eight years in office as a Democratic president from 2009-2017, and as to the person who is Obama. Helping us in the formulation of our views on Obama and his presidency, is Ben Rhodes book, The World As It Is: Inside the Obama White House.

As the first African American president of the United States (US), Barack Obama is a uniquely historical personality. Each of us has our opinions, or will formulate opinions, as to the success or limitations of his eight years in office as a Democratic president from 2009-2017, and as to the person who is Obama. Helping us in the formulation of our views on Obama and his presidency, is Ben Rhodes book, The World As It Is: Inside the Obama White House.

One of the things I love about sports is they’re a low-stakes environment in which to practice high-stakes skills. For most people, most of the time, the results of a sporting match don’t affect the long-term quality of their lives. This is what I mean by “low-stakes.” In the grand scheme and scope of our lives, the outcomes of games rarely matter. Which is what makes sports such a great place to practice skills that really can and do impact our lives for the better. This is what I mean by “high-stakes.”

One of the things I love about sports is they’re a low-stakes environment in which to practice high-stakes skills. For most people, most of the time, the results of a sporting match don’t affect the long-term quality of their lives. This is what I mean by “low-stakes.” In the grand scheme and scope of our lives, the outcomes of games rarely matter. Which is what makes sports such a great place to practice skills that really can and do impact our lives for the better. This is what I mean by “high-stakes.” In the fall of 1970, I brought a Bundy tenor saxophone home from school. I was nine and in Mrs Farrar’s 5th grade class. To celebrate, my father slid an LP called “Soultrane”out of a blue and white cardboard jacket. The first sounds from the record player’s single speaker: a muscular folk song with rippling connective tissue that quickly spun free into endless cascades. Dad explained that it was my new horn, in the hands of John Coltrane. I didn’t know his name and nothing that day seemed possible, anyway.

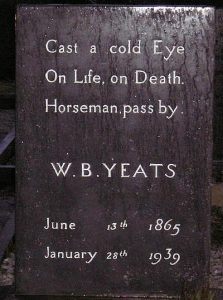

In the fall of 1970, I brought a Bundy tenor saxophone home from school. I was nine and in Mrs Farrar’s 5th grade class. To celebrate, my father slid an LP called “Soultrane”out of a blue and white cardboard jacket. The first sounds from the record player’s single speaker: a muscular folk song with rippling connective tissue that quickly spun free into endless cascades. Dad explained that it was my new horn, in the hands of John Coltrane. I didn’t know his name and nothing that day seemed possible, anyway. Thirty years ago last week, Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses was published. Rushdie was then perhaps the most celebrated British novelist of his generation. His new novel, five years in the making, had been expected to set the world alight, though not quite in the way that it did.

Thirty years ago last week, Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses was published. Rushdie was then perhaps the most celebrated British novelist of his generation. His new novel, five years in the making, had been expected to set the world alight, though not quite in the way that it did.