Category: Archives

Geta Brătescu (1926 – 2018)

Otis Rush (1935 – 2018)

Sunday Poem

FOG

A vagueness comes over everything,

as though proving color and contour

alike dispensable: the lighthouse

extinct, the islands’ spruce-tips

drunk up like milk in the

universal emulsion; houses

reverting into the lost

and forgotten; granite

subsumed, a rumor

in a mumble of ocean.

Tactile

definition, however, has not been

totally banished: hanging

tassel by tassel, panicled

foxtail and needlegrass,

dropseed, furred hawkweed,

and last season’s rose-hips

are vested in silenced

chimes of the finest,

clearest sea-crystal.

Opacity

opens up rooms, a showcase

for the hueless moonflower

corolla, as Georgia

O’Keefe might have seen it,

of foghorns; the nodding

campanula of bell buoys;

the ticking, linear

filigree of bird voices.

by Amy Clampitt

from The Collected Poems of Amy Clampitt

published by Alfred A. Knopf, 1997.

A New Project Weaves Patient Stories Into Art

Giovanni Biglino in Smithsonian:

When working with people in other disciplines – whether surgeons, fellow engineers, nurses or cardiologists – it can sometimes seem like everyone is speaking a different language. But collaboration between disciplines is crucial for coming up with new ideas.

When working with people in other disciplines – whether surgeons, fellow engineers, nurses or cardiologists – it can sometimes seem like everyone is speaking a different language. But collaboration between disciplines is crucial for coming up with new ideas.

I first became fascinated with the workings of the heart years ago, during a summer research project on the aortic valve. And as a bioengineer, I recently worked with an artist, a psychologist, a producer, a literature scholar and a whole interdisciplinary team to understand even more about the heart, its function and its symbolism. We began to see the heart in completely different ways. The project, The Heart of the Matter, also involved something that is often missing from discussions purely centred around research: stories from the patients themselves. The Heart of the Matter originally came out of artist Sofie Layton’s residency at Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children in London a couple of years ago, before the project grew into a wider collaborative effort. For the project, patient groups were engaged in creative workshops that explored how they viewed their hearts. Stories that emerged from these sessions were then translated into a series of original artworks that allow us to reflect on the medical and metaphorical dimensions of the heart, including key elements of cardiovascular function and patient experience.

More here.

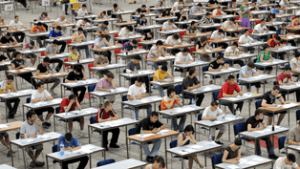

Your IQ Matters Less Than You Think

Dean Keith Simonton in Nautilus:

People too often forget that IQ tests haven’t been around that long. Indeed, such psychological measures are only about a century old. Early versions appeared in France with the work of Alfred Binet and Theodore Simon in 1905. However, these tests didn’t become associated with genius until the measure moved from the Sorbonne in Paris to Stanford University in Northern California. There Professor Lewis M. Terman had it translated from French into English, and then standardized on sufficient numbers of children, to create what became known as the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale. That happened in 1916. The original motive behind these tests was to get a diagnostic to select children at the lower ends of the intelligence scale who might need special education to keep up with the school curriculum. But then Terman got a brilliant idea: Why not study a large sample of children who score at the top end of the scale? Better yet, why not keep track of these children as they pass into adolescence and adulthood? Would these intellectually gifted children grow up to become genius adults?

People too often forget that IQ tests haven’t been around that long. Indeed, such psychological measures are only about a century old. Early versions appeared in France with the work of Alfred Binet and Theodore Simon in 1905. However, these tests didn’t become associated with genius until the measure moved from the Sorbonne in Paris to Stanford University in Northern California. There Professor Lewis M. Terman had it translated from French into English, and then standardized on sufficient numbers of children, to create what became known as the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale. That happened in 1916. The original motive behind these tests was to get a diagnostic to select children at the lower ends of the intelligence scale who might need special education to keep up with the school curriculum. But then Terman got a brilliant idea: Why not study a large sample of children who score at the top end of the scale? Better yet, why not keep track of these children as they pass into adolescence and adulthood? Would these intellectually gifted children grow up to become genius adults?

Terman subjected hundreds of school kids to his newfangled IQ test. Obviously, he didn’t want a sample so large that it would be impractical to follow their intellectual development. Taking the top 2 percent of the population would clearly yield a group twice as large as the top 1 percent. Moreover, a less select group might be less prone to become geniuses. So why not catch the crème de la crème? The result was a group of 1,528 extremely bright boys and girls who averaged around 11 years old. And to say they were “bright” is a very big understatement. Their average IQ was 151, with 77 claiming IQs between 177 and 200. These children were subjected to all sorts of additional tests and measures, repeatedly so, until they reached middle age. The result was the monumental Genetic Studies of Genius, five volumes appearing between 1925 and 1959, although Terman died before the last volume came out. These highly intelligent people are still being studied today, or at least the small number still alive. They have also become affectionately known as “Termites”—a clear contraction of “Termanites.”

More here.

Saturday, October 6, 2018

Michael Lewis Makes a Story About Government Infrastructure Exciting

Jennifer Szalai in the New York Times:

“Many of the problems our government grapples with aren’t particularly ideological,” Lewis writes, by way of moseying into what his book is about. He identifies these problems as the “enduring technical” variety, like stopping a virus or taking a census. Lewis is a supple and seductive storyteller, so you’ll be turning the pages as he recounts the (often surprising) experiences of amiable civil servants and enumerating risks one through four (an attack by North Korea, war with Iran, etc.) before you learn that the scary-sounding “fifth risk” of the title is — brace yourself — “project management.”

“Many of the problems our government grapples with aren’t particularly ideological,” Lewis writes, by way of moseying into what his book is about. He identifies these problems as the “enduring technical” variety, like stopping a virus or taking a census. Lewis is a supple and seductive storyteller, so you’ll be turning the pages as he recounts the (often surprising) experiences of amiable civil servants and enumerating risks one through four (an attack by North Korea, war with Iran, etc.) before you learn that the scary-sounding “fifth risk” of the title is — brace yourself — “project management.”

More here.

Welfare was meant to help the poor, not subsidise exploitative employers

Kenan Malik in The Guardian:

It will mean fewer jobs. That was the chorus from many on the right, from Tej Parikh of the Institute of Directors to the chancellor, Philip Hammond, in response to proposals from the shadow chancellor, John McDonnell, to improve conditions for gig economy workers. Such workers, he insisted, should be given similar rights to those in permanent work, including eligibility for sick pay, maternity pay and similar benefits. He promised to ban zero-hours contracts and introduce a “real living wage” of £10 an hour.

It will mean fewer jobs. That was the chorus from many on the right, from Tej Parikh of the Institute of Directors to the chancellor, Philip Hammond, in response to proposals from the shadow chancellor, John McDonnell, to improve conditions for gig economy workers. Such workers, he insisted, should be given similar rights to those in permanent work, including eligibility for sick pay, maternity pay and similar benefits. He promised to ban zero-hours contracts and introduce a “real living wage” of £10 an hour.

So what does it mean for Parikh and Hammond to insist that if gig workers are given decent benefits, jobs will be lost? Unpacked, what that suggests is that employers are willing, or able, to provide jobs only if workers accept low pay and poor conditions.

Put like that, few people would accept the moral logic of the argument. But it is rarely put like that. We take for granted that businesses create jobs and so have the right to dictate on what conditions jobs are created.

This is one reason that we have come to accept, with little political debate or fury, the existence of the “working poor”. Almost 60% of the poor now live in households where at least one person has a job, a figure more than 20% higher than in 1995. Few are stereotypical gig economy workers such as Uber drivers or fruit pickers. They are cleaners and call centre workers, waiters and shelf stackers, childminders and rubbish collectors, workers whose labour is essential to society but whose pay and conditions push them to the margins.

Poverty is often seen as a problem of worklessness. Today, though, it is a problem of being in work.

More here.

Brief But Spectacular: Flossie Lewis, back by popular demand

The Ultimate Sitcom

Sam Anderson in the New York Times:

How do hands move in heaven? Ted Danson knows. Watch him in “The Good Place,” NBC’s circle-squaring philosophical sitcom about life, death, good, evil, redemption and frozen yogurt. As Danson speaks, his hands flutter and hover in front of him like a pair of trained birds. They poke and swirl, pinch and twist. They snap suddenly ahead to accent a word as if they’re plucking a feather from a passing breeze. Danson is tall and slim — he was a basketball star growing up — and his hands are expressively large. He can move them, when he needs to, with the long-fingered languor of Michelangelo’s God reaching out to touch Adam. On the show, Danson plays an “architect” of the afterlife named Michael, a sort of immortal Willy Wonka who dresses in bright suits and bow ties. He is always flying into spasms of delight over the fascinating novelties of human culture — paper clips, suspenders, karaoke, Skee-Ball — and in one scene he gets so celestially excited that he lunges into a squat, holds his arms out in front of him and gyrates his wrists like an electric mixer on full blast. “How do you pump your fist again?” he asks. “Is this it?”

How do hands move in heaven? Ted Danson knows. Watch him in “The Good Place,” NBC’s circle-squaring philosophical sitcom about life, death, good, evil, redemption and frozen yogurt. As Danson speaks, his hands flutter and hover in front of him like a pair of trained birds. They poke and swirl, pinch and twist. They snap suddenly ahead to accent a word as if they’re plucking a feather from a passing breeze. Danson is tall and slim — he was a basketball star growing up — and his hands are expressively large. He can move them, when he needs to, with the long-fingered languor of Michelangelo’s God reaching out to touch Adam. On the show, Danson plays an “architect” of the afterlife named Michael, a sort of immortal Willy Wonka who dresses in bright suits and bow ties. He is always flying into spasms of delight over the fascinating novelties of human culture — paper clips, suspenders, karaoke, Skee-Ball — and in one scene he gets so celestially excited that he lunges into a squat, holds his arms out in front of him and gyrates his wrists like an electric mixer on full blast. “How do you pump your fist again?” he asks. “Is this it?”

Danson is now 70, roughly twice the age he was when he started on “Cheers,” and he carries his seniority around as if it were the funniest thing in the world.

More here.

Belief is Back: Why The World Is Putting its Faith in Religion

Neil MacGregor at The Guardian:

Belief is back. Around the world, religion is once again politically centre stage. It is a development that seems to surprise and bewilder, indeed often to anger, the agnostic, prosperous west. Yet if we do not understand why religion can mobilise communities in this way, we have little chance of successfully managing the consequences.

Belief is back. Around the world, religion is once again politically centre stage. It is a development that seems to surprise and bewilder, indeed often to anger, the agnostic, prosperous west. Yet if we do not understand why religion can mobilise communities in this way, we have little chance of successfully managing the consequences.

If one had to choose a tipping point, a specific moment at which this change crystallised, it would probably be the 1979 Islamic revolution in Iran. Deeply shocking to the secular world, it appeared at the time to be pushing against the tide of history: now it seems instead to have been the harbinger of its turning. After decades of humiliating intervention by the British and the Americans, dissenting Iranian politicians – many of them far from devout – saw in the forms of Iranian Shi’ism a way of defining and asserting the country’s identity against the outsiders. The mosque, even more than the bazaar, was the space in which new national narratives could be devised and in which all of society could engage.

more here.

‘After the Winter’ by Guadalupe Nettel

Walter Biggins at The Quarterly Conversation:

In capturing the voices, travails, and eventual connection of two lonelyhearts, Guadalupe Nettel’s After the Winter captures the spirit of urban loneliness so vividly that it’s often painful to read. But, as with her story collection Natural Histories (2013) and novel The Body Where I Was Born (2011), Nettel casts a sardonic, cocked eye at all the sadness. She’s funny, wickedly so, just as much as she shows us these lonely souls from the perspectives of others.

In capturing the voices, travails, and eventual connection of two lonelyhearts, Guadalupe Nettel’s After the Winter captures the spirit of urban loneliness so vividly that it’s often painful to read. But, as with her story collection Natural Histories (2013) and novel The Body Where I Was Born (2011), Nettel casts a sardonic, cocked eye at all the sadness. She’s funny, wickedly so, just as much as she shows us these lonely souls from the perspectives of others.

Nettel’s alternate points-of-view are initially hard to see, as After the Winter is resolutely told from the first-person. The chapters alternate between Claudio, a Cuban expat in New York, and Cecilia, a Mexican expat in Paris. The narratives build separately as they evoke their funny, sad lives, until the moment that these lives—and their love and loin—converge. Until that union, these two are trapped in their own heads and cluttered apartments.

more here.

Lady Gaga’s ‘A Star is Born’

Naomi Fry at The New Yorker:

If it sounds as if the movie’s depiction of authenticity, especially in the case of Gaga, is somehow blinkered, this isn’t the case. “Gaga: Five Foot Two,” in its focus on its subject’s usually concealed struggles, willfully disregarded the showiness inherent even in her most private actions. “A Star Is Born,” however, is able to accommodate exactly this doubleness. Cooper’s movie presents itself as the greatest love story ever told. It’s an emotional blockbuster, visually grand, and, within the logic of its world, meaningful gestures undertaken by larger-than-life characters—a single tear trailing down Ally’s face, Maines’s finger tracing the outline of her strong nose, Ally cupping Maines’s cheek—take on a duality that Gaga’s skills are exactly made for. She is both the dressed-down girl next door and the mythical superstar, and her ability to nimbly straddle these two poles is what makes her performance great. What came across in the documentary as an uncomfortable mix produces a satisfying combination in an outsized epos like this one, the two impulses tempering and complementing each other.

If it sounds as if the movie’s depiction of authenticity, especially in the case of Gaga, is somehow blinkered, this isn’t the case. “Gaga: Five Foot Two,” in its focus on its subject’s usually concealed struggles, willfully disregarded the showiness inherent even in her most private actions. “A Star Is Born,” however, is able to accommodate exactly this doubleness. Cooper’s movie presents itself as the greatest love story ever told. It’s an emotional blockbuster, visually grand, and, within the logic of its world, meaningful gestures undertaken by larger-than-life characters—a single tear trailing down Ally’s face, Maines’s finger tracing the outline of her strong nose, Ally cupping Maines’s cheek—take on a duality that Gaga’s skills are exactly made for. She is both the dressed-down girl next door and the mythical superstar, and her ability to nimbly straddle these two poles is what makes her performance great. What came across in the documentary as an uncomfortable mix produces a satisfying combination in an outsized epos like this one, the two impulses tempering and complementing each other.

more here.

Resisting the Juristocracy

Sam Moyn in The Boston Review:

Sam Moyn in The Boston Review:

Affirmative action will be the first to go, with Justice Kavanaugh’s vote. A federal abortion right is also on the chopping block, with the main question remaining whether it will die in a single blow or a succession of smaller ones. The First Amendment will continue to be “weaponized” in the service of economic power, as Justice Elena Kagan put it last term. And the rest of constitutional law will turn into a defense of business interests and corporate might the likes of which the country has not seen in a century.

Which brings us back to Franklin Roosevelt’s mistake and our opportunity. The last time the court was converted into a tool of the rich and powerful against political majorities, Roosevelt tried to pack the court. Once the Democrats had finally gathered enough political will to stand the Court down, Roosevelt told the American people in March of 1937 that it was time to “save the Constitution from the Court and the Court from itself.”

But the Constitution is what got us here, along with longstanding interpretations of it such as Marbury v. Madison that transform popular rule into elite rule and democracy into juristocracy. Only because of the constitution do Democrats have to battle in a political system in which minorities take the presidency—twice in our lifetime. Only because of a cult of the higher judiciary do Democrats find themselves facing an all-powerful institution set to impose its will on a majority of Americans who would decide things differently.

More here.

How the World Thinks – a global history of philosophy

Tim Whitmarsh in The Guardian:

Ancient Greeks often wondered whether non-Greeks could do philosophy. Some thought the discipline had its origins in the wisdom of Egypt and Mesopotamia. Some counted itinerant Scythian sages or Jewish preachers as philosophers. Others said no: whatever the intellectual merits of neighbouring peoples, it is a distinctively Greek practice. A new, angrier version of that ancient debate has arisen amid the culture wars of the last 50 years. Is philosophy an exclusively western phenomenon? Or is denying it to non-western peoples a form of neocolonialism? Or does the imperialism lie, rather, in folding non-western thought into a western category? Difficult questions, and the answers are not always obvious.

Ancient Greeks often wondered whether non-Greeks could do philosophy. Some thought the discipline had its origins in the wisdom of Egypt and Mesopotamia. Some counted itinerant Scythian sages or Jewish preachers as philosophers. Others said no: whatever the intellectual merits of neighbouring peoples, it is a distinctively Greek practice. A new, angrier version of that ancient debate has arisen amid the culture wars of the last 50 years. Is philosophy an exclusively western phenomenon? Or is denying it to non-western peoples a form of neocolonialism? Or does the imperialism lie, rather, in folding non-western thought into a western category? Difficult questions, and the answers are not always obvious.

Julian Baggini’s contribution is an engaging, urbane and humane global history. “History” here is a misnomer: this is not a systematic, chronological exposition of different intellectual traditions (anyone wanting that is better off with Peter Adamson’s podcast series Philosophy Without Any Gapshttps://historyofphilosophy.net/). Baggini’s strengths lie not in history (as is revealed, for example, when he ill-advisedly ticks off the Greek archaeological authorities for not advertising the Areopagus as the site of Socrates’ trial) but in a clear-sighted ability to boil complex arguments down to their essentials, and so to allow many different voices from across the world to converse in a virtual dialogue. In his view, people everywhere grapple with the same moral questions, which are fundamentally about balancing contradictory imperatives: individual autonomy versus collective good; the social need for impartial arbiters of truth versus awareness of subjective experience; adherence to rules versus commonsense flexibility; and so forth. The differences between people lie not in the issues they face, but in the positions they end up adopting on the scale between the extremes. The analogy he draws is with a producer in a recording studio: “By sliding controls up or down, the volume of each track can be increased or decreased.” All cultures play the same song, but some prefer the cymbals higher up in the mix.

More here.

Saturday Poem

Ringing Doorbells

that night for Gene

McCarthy at the edge

of Little Italy

turned into

an olfactory

adventure: after

the mildew, after

the musts and fetors

of tomcat and cockroach,

barrooms’ beer-reek,

the hayfield whiff

of pot, hot air

of laundromats

a flux of borax

the entire effluvium

of the polluted

Hudson opened

like a hidden

fault line, and from

a cleft between the

backs of buildings

blossomed, out of

the dark, as

with hosannas,

the ageless,

pristine, down-

to-earth aromas

of tomorrow’s

bread from

Zito’s Bakery.

Amy Clampitt

from: Collected Poems

Alfred Knopf, 2003

Friday, October 5, 2018

Where does hate come from, and why has it played such a role in recent political history?

Ian Hughes in Open Democracy:

Is it possible to transform politics around values such as empathy, solidarity and love? Many progressive commentators think so, and have laid out different plans to put these ideas into practice. But empathy and love seem in short supply in the actuality of politics today, crowded out by hate and intolerance. In one society after another fear-mongering proceeds apace against poor people, immigrants, minorities and anyone else who is not part of the dominant group.

Is it possible to transform politics around values such as empathy, solidarity and love? Many progressive commentators think so, and have laid out different plans to put these ideas into practice. But empathy and love seem in short supply in the actuality of politics today, crowded out by hate and intolerance. In one society after another fear-mongering proceeds apace against poor people, immigrants, minorities and anyone else who is not part of the dominant group.

Politics have always been animated as much by passions as by policies, but we can’t assume those passions will be positive. Therefore it’s incumbent on us to understand how negative emotions play out in politics and how politicians exploit these feelings to advance their agendas. Where does hate come from, and why has it played such a role in recent political history?

According to psychologist Robert Sternberg hatred is not a single emotion, but instead comprises three distinct components. The first of these components is the negation of intimacy. Instead of wanting to be close to others, hatred grips us with a feeling of repulsion, an impulse to distance ourselves from the hated other.

More here.

To make better biomedical research tools, a grad student picks apart fireflies’ glow

Eric Boodman in STAT News:

A few hours after sunset one night in July of 2016, a Ph.D. student walked into a New Jersey hotel carrying a bouquet of butterfly nets. The travelers who usually occupy the place looked up from their lonely business trips, curious to hear what Tim Fallon had caught. Tangled up in the mesh, he said, were about 100 fireflies, freshly nabbed from a local meadow as they blinked their way toward reproductive fulfillment.

A few hours after sunset one night in July of 2016, a Ph.D. student walked into a New Jersey hotel carrying a bouquet of butterfly nets. The travelers who usually occupy the place looked up from their lonely business trips, curious to hear what Tim Fallon had caught. Tangled up in the mesh, he said, were about 100 fireflies, freshly nabbed from a local meadow as they blinked their way toward reproductive fulfillment.

He’d interrupted their mating dance for a worthy cause: figuring out how these insects first acquired the ability to glow — and hopefully, in the process, finding better laboratory tools for studying disease and developing treatments. Now, two years later, his team from the MIT-affiliated Whitehead Institute is publishing this firefly’s genome for the first time. It will appear next week in the journal eLife.

Among the key results: Bioluminescence evolved separately in fireflies and certain other species of beetles. But the findings won’t just be scoured by entomologists and evolutionary biologists.

“The data provided can (will) be used by others,” said Hugo Fraga, a biochemist at the Institut de Biologie Structurale, in Grenoble, France, who has done research on firefly chemistry, and who was not involved in this study. “The same way the human genome … provides a map for other researchers.”

More here.

‘Sokal Squared’: Is Huge Publishing Hoax ‘Hilarious and Delightful’ or an Ugly Example of Dishonesty and Bad Faith?

Alexander C. Kafka in the Chronicle of Higher Education:

Some scholars applauded the hoax.

Some scholars applauded the hoax.

“Is there any idea so outlandish that it won’t be published in a Critical/PoMo/Identity/‘Theory’ journal?” tweeted the Harvard psychologist Steven Pinker.

“Three intrepid academics,” wrote Yascha Mounk, an author and lecturer on government at Harvard, “just perpetrated a giant version of the Sokal Hoax, placing … fake papers in major academic journals. Call it Sokal Squared. The result is hilarious and delightful. It also showcases a serious problem with big parts of academia.”

In the original Sokal Hoax, in 1996, a New York University physicist named Alan Sokal published a bogus paper that took aim at some of the same targets as his latter-day successors.

Others were less receptive than Mounk. “This is a genre,” tweeted Kieran Healy, a sociologist at Duke, “and they’re in it for the lulz” — the laughs. “Best not to lose sight of that.”

“Good work is hard to do,” he wrote, “incentives to publish are perverse; there’s a lot of crap out there; if you hate an area enough, you can gin up a fake paper and get it published somewhere if you try. The question is, what do you hate? And why is that?”

More here.

The Grievance Studies Scandal: Five Academics Respond

From Quillette:

Editor’s note: For the past year scholars James Lindsay, Helen Pluckrose, and Peter Boghossian have sent fake papers to various academic journals which they describe as specialising in activism or “grievance studies.” Their stated mission has been to expose how easy it is to get “absurdities and morally fashionable political ideas published as legitimate academic research.”

Editor’s note: For the past year scholars James Lindsay, Helen Pluckrose, and Peter Boghossian have sent fake papers to various academic journals which they describe as specialising in activism or “grievance studies.” Their stated mission has been to expose how easy it is to get “absurdities and morally fashionable political ideas published as legitimate academic research.”

To date, their project has been successful: seven papers have passed through peer review and have been published, including a 3000 word excerpt of Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf, rewritten in the language of Intersectionality theory and published in the Gender Studies journal Affilia.

From Foolish Talk to Evil Madness — Nathan Cofnas

Twenty years ago, Alan Sokal called postmodernism “fashionable nonsense.” Today, postmodernism isn’t a fashion—it’s our culture. A large proportion of the students at elite universities are now inducted into this cult of hate, ignorance, and pseudo-philosophy. Postmodernism is the unquestioned dogma of the literary intellectual class and the art establishment. It has taken over most of the humanities and some of the social sciences, and is even making inroads in STEM fields. It threatens to melt all of our intellectual traditions into the same oozing mush of political slogans and empty verbiage.

Postmodernists pretend to be experts in what they call “theory.” They claim that, although their scholarship may seem incomprehensible, this is because they are like mathematicians or physicists: they express profound truths in a way that cannot be understood without training. Lindsay, Boghossian, and Pluckrose expose this for the lie that it is. “Theory” is not real. Postmodernists have no expertise and no profound understanding.

More here.