Ray Monk in New Statesman:

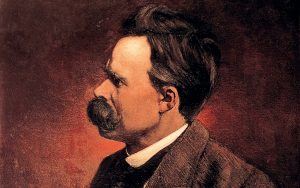

The Nietzsche scholar Walter Kaufmann told a story of how, in 1952, just two years after publishing his ground-breaking book, Nietzsche: Philosopher, Psychologist, Antichrist, he visited the Cambridge philosopher CD Broad at Trinity College. During their conversation, Broad mentioned someone by the name of Salter. Was that, Kaufmann asked, the Salter who had written a book on Nietzsche? “Dear no,” Broad replied, “he did not deal with crackpot subjects like that; he wrote about psychical research.” In the years immediately before, during and just after the Second World War, Nietzsche’s reputation in the English-speaking world was at its lowest, largely owing to the fact that his work had been, with the support of his virulently anti-Semitic sister Elisabeth, appropriated by the Nazis. In their hands, Nietzsche’s notion of the Übermensch (I prefer to use the original German than any of the published translations; “superman” sounds silly, and “beyond-man” and “overman” do not sound like natural English) became associated with notions of Aryan racial superiority, while his idea of the “will to power” was used to justify militarism and authoritarianism.

The Nietzsche scholar Walter Kaufmann told a story of how, in 1952, just two years after publishing his ground-breaking book, Nietzsche: Philosopher, Psychologist, Antichrist, he visited the Cambridge philosopher CD Broad at Trinity College. During their conversation, Broad mentioned someone by the name of Salter. Was that, Kaufmann asked, the Salter who had written a book on Nietzsche? “Dear no,” Broad replied, “he did not deal with crackpot subjects like that; he wrote about psychical research.” In the years immediately before, during and just after the Second World War, Nietzsche’s reputation in the English-speaking world was at its lowest, largely owing to the fact that his work had been, with the support of his virulently anti-Semitic sister Elisabeth, appropriated by the Nazis. In their hands, Nietzsche’s notion of the Übermensch (I prefer to use the original German than any of the published translations; “superman” sounds silly, and “beyond-man” and “overman” do not sound like natural English) became associated with notions of Aryan racial superiority, while his idea of the “will to power” was used to justify militarism and authoritarianism.

In the chapter on Nietzsche in his History of Western Philosophy, published in 1946, Bertrand Russell went some way towards correcting some of these Nazi-led misunderstandings, emphasising that Nietzsche was far from being a nationalist, a racist, a worshipper of the state, or a German supremacist (his writings are in fact full of anti-German sentiment). Russell, however, could not free himself from his times sufficiently to avoid misrepresenting Nietzsche’s notion of the will to power. Nietzsche’s ethic, Russell claims, can be summed up by saying: “Victors in war, and their descendants, are usually biologically superior to the vanquished. It is therefore desirable that they should hold all the power, and should manage affairs exclusively in their own interests.” Russell’s chapter ends with a statement that has often been quoted and which helped to shape Nietzsche’s reputation among English-speaking people for a generation: “I dislike Nietzsche because he likes the contemplation of pain… because the men whom he most admires are conquerors, whose glory is cleverness in causing men to die.”

More here.