Rachel M. Cohen in The Intercept:

Rachel M. Cohen in The Intercept:

ASIDE FROM BEING a way to address inequality, the impending “silver tsunami” — the wave of baby boomer retirements expected over the next decade — is another reason ESOPs are gaining traction. According to a 2017 study by the worker ownership group Project Equity, 2.3 million businesses are owned by baby boomers who are approaching retirement, and these companies employ almost 25 million Americans.

While many of these business owners will fold quietly and sell their companies to competitors or private equity firms, ESOPs offer owners another alternative: selling the company to its workers. Advocates say this can help to better ensure that jobs remain in the local community, while still allowing the retiring owner to cash out. According to Project Equity, one-third of business owners over age 50 report having a hard time finding a buyer for their company. As a result, many just quietly close up shop, often without even considering selling their company to the staff.

But if ESOPs really can yield such positive results — for workers, owners, and local economies — why do they remain so obscure?

More here.

Joseph Stiglitz in Project Syndicate:

Joseph Stiglitz in Project Syndicate: Edmundson’s project is a religious (or spiritual) attempt to discover alternatives to the everyday world of late-modern capitalism. No dogma is involved, save the premise of the book itself: namely, that ideals matter profoundly, and we can discover and use them through reading great literature. This is, one might say, the religion of ideals, a holding space between pure secularity and traditional religion. Its sole purpose is to say that somethingmatters more than our petty concerns with self-advancement, and through openness to that something we might encounter ways of life worth living.

Edmundson’s project is a religious (or spiritual) attempt to discover alternatives to the everyday world of late-modern capitalism. No dogma is involved, save the premise of the book itself: namely, that ideals matter profoundly, and we can discover and use them through reading great literature. This is, one might say, the religion of ideals, a holding space between pure secularity and traditional religion. Its sole purpose is to say that somethingmatters more than our petty concerns with self-advancement, and through openness to that something we might encounter ways of life worth living. The Met’s permanent collection can tell you much about the Greeks and Romans, the Babylonians and the Assyrians, medieval Japan and the many dynasties of China, but it does not have as much to say about more marginal peoples. History, here, gathers at the center. If one wants to see peripheries, one must look for them. Wandering the galleries, one rarely get a sense of the vast mosaic of peoples who lived within and often long past those great empires of stone, paper, and capital. The presence of so many Armenian works, directly beside sculpture from Pergamon and Rome, offers an alternative view of history, one in which time eventually pulls down the mighty from their thrones and sometimes lifts up the lowly. The margins come into focus.

The Met’s permanent collection can tell you much about the Greeks and Romans, the Babylonians and the Assyrians, medieval Japan and the many dynasties of China, but it does not have as much to say about more marginal peoples. History, here, gathers at the center. If one wants to see peripheries, one must look for them. Wandering the galleries, one rarely get a sense of the vast mosaic of peoples who lived within and often long past those great empires of stone, paper, and capital. The presence of so many Armenian works, directly beside sculpture from Pergamon and Rome, offers an alternative view of history, one in which time eventually pulls down the mighty from their thrones and sometimes lifts up the lowly. The margins come into focus. Around 1730 Johann Sebastian Bach began to recycle his earlier works in a major way. He was in his mid-forties at the time, and he had composed hundreds of masterful keyboard, instrumental, and vocal pieces, including at least three annual cycles of approximately sixty cantatas each for worship services in Leipzig, where he was serving as St. Thomas Cantor and town music director. Bach was at the peak of his creative powers. Yet for some reason, instead of sitting down and writing original music, he turned increasingly to old compositions, pulling them off the shelf and using their contents as the basis for new works.

Around 1730 Johann Sebastian Bach began to recycle his earlier works in a major way. He was in his mid-forties at the time, and he had composed hundreds of masterful keyboard, instrumental, and vocal pieces, including at least three annual cycles of approximately sixty cantatas each for worship services in Leipzig, where he was serving as St. Thomas Cantor and town music director. Bach was at the peak of his creative powers. Yet for some reason, instead of sitting down and writing original music, he turned increasingly to old compositions, pulling them off the shelf and using their contents as the basis for new works. “There’s a question I get asked a lot,” Jimmy Kimmel

“There’s a question I get asked a lot,” Jimmy Kimmel  When the news broke that

When the news broke that  On Friday afternoon, a text arrived from Israel letting me know of

On Friday afternoon, a text arrived from Israel letting me know of  Is Allah, the God of Muslims, a different deity from the one worshiped by Jews and Christians? Is he even perhaps a strange “moon god,” a relic from Arab paganism, as some anti-Islamic polemicists have argued? What about Allah’s apostle, Muhammad? Was he a militant prophet who imposed his new religion by the sword, leaving a bellicose legacy that still drives today’s Muslim terrorists? Two new books may help answer such questions, and also give a deeper understanding of Islam’s theology and history.

Is Allah, the God of Muslims, a different deity from the one worshiped by Jews and Christians? Is he even perhaps a strange “moon god,” a relic from Arab paganism, as some anti-Islamic polemicists have argued? What about Allah’s apostle, Muhammad? Was he a militant prophet who imposed his new religion by the sword, leaving a bellicose legacy that still drives today’s Muslim terrorists? Two new books may help answer such questions, and also give a deeper understanding of Islam’s theology and history. In his classic 1923 essay, “

In his classic 1923 essay, “ Every time we look at a face, we take in a flood of information effortlessly: age, gender, race, expression, the direction of our subject’s gaze, perhaps even their mood. Faces draw us in and help us navigate relationships and the world around us.

Every time we look at a face, we take in a flood of information effortlessly: age, gender, race, expression, the direction of our subject’s gaze, perhaps even their mood. Faces draw us in and help us navigate relationships and the world around us. Hugh Ryan in The Boston Review:

Hugh Ryan in The Boston Review: James McAuley and Greil Marcus, and a reply by Mark Lilla in the New York Review of Books:

James McAuley and Greil Marcus, and a reply by Mark Lilla in the New York Review of Books: WHEN

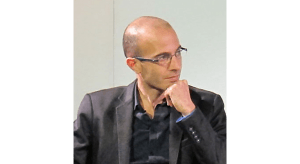

WHEN Just a few years ago Yuval Noah Harari was an obscure Israeli historian with a knack for playing with big ideas. Then he wrote Sapiens, a sweeping, cross-disciplinary account of human history that landed on the bestseller list and remains there four years later. Like Jared Diamond’s Guns, Germs and Steel, Sapiens proposed a dazzling historical synthesis, and Harari’s own quirky pronouncements—“modern industrial agriculture might well be the greatest crime in history”— made for compulsive reading. The book also won him a slew of high-profile admirers, including Barack Obama, Bill Gates, and Mark Zuckerberg.

Just a few years ago Yuval Noah Harari was an obscure Israeli historian with a knack for playing with big ideas. Then he wrote Sapiens, a sweeping, cross-disciplinary account of human history that landed on the bestseller list and remains there four years later. Like Jared Diamond’s Guns, Germs and Steel, Sapiens proposed a dazzling historical synthesis, and Harari’s own quirky pronouncements—“modern industrial agriculture might well be the greatest crime in history”— made for compulsive reading. The book also won him a slew of high-profile admirers, including Barack Obama, Bill Gates, and Mark Zuckerberg. But Einstein’s was a God of philosophy, not religion. When asked many years later whether he believed in God, he replied: ‘I believe in Spinoza’s God, who reveals himself in the lawful harmony of all that exists, but not in a God who concerns himself with the fate and the doings of mankind.’ Baruch Spinoza, a contemporary of Isaac Newton and Gottfried Leibniz, had conceived of God as identical with nature. For this, he was considered a dangerous

But Einstein’s was a God of philosophy, not religion. When asked many years later whether he believed in God, he replied: ‘I believe in Spinoza’s God, who reveals himself in the lawful harmony of all that exists, but not in a God who concerns himself with the fate and the doings of mankind.’ Baruch Spinoza, a contemporary of Isaac Newton and Gottfried Leibniz, had conceived of God as identical with nature. For this, he was considered a dangerous