by Gabrielle C. Durham

In the immortal words of Prince Rogers Nelson’s party gem from 1982:

In the immortal words of Prince Rogers Nelson’s party gem from 1982:

“But life is just a party, and parties weren’t meant to last . . .

“So tonight I’m gonna party like it’s 1999.”

So much fun stuff happened in 1999: rampant concern about Y2K; the movie “The Matrix” came out; Bill Clinton’s ongoing inability to keep his dick in his pants and subsequent impeachment and acquittal; former pro wrestler Jesse Ventura became governor of Minnesota; U.S. military college The Citadel graduated its first female cadet; the Elian Gonzalez controversy raged in the States; and Cher’s single “Believe” was released.

But do you remember what you said? Do you remember when something made you laugh, not LOL? It was not actually all that long ago, TBH. Back in 1999, reading a text typically meant applying a highlighter, most likely in neon yellow, to the testable information in a book or handout that the teacher assigned. It has a very different meaning from today’s pithier text message. In a score of years, English has changed. Duh, language is always changing; that’s how it stays alive. But if we think about it at all, we think of language change as being in evolutionary terms – something that takes generations, but it actually happens much more quickly. Read more »

Simple questions often yield complex answers. For instance: what is the difference between a language and a dialect? If you ask this of a linguist, get comfortable. Despite the simplicity of the query, there are a lot of possible answers.

Simple questions often yield complex answers. For instance: what is the difference between a language and a dialect? If you ask this of a linguist, get comfortable. Despite the simplicity of the query, there are a lot of possible answers. If you can believe it, Japanese novelist, talking cat enthusiast, and weird ear chronicler Haruki Murakami turned 70 years old this weekend. 70! But I suppose we should believe it, despite the youthful gaiety and creative magic of his prose: the internationally bestselling writer has 14 novels and a handful of short stories under his belt, and it’s safe to say he’s one of the most famous contemporary writers in the world. To celebrate his birthday, and as a gift to those of you who hope to be the kind of writer Murakami is when you turn 70, I’ve collected some of his best writing advice below.

If you can believe it, Japanese novelist, talking cat enthusiast, and weird ear chronicler Haruki Murakami turned 70 years old this weekend. 70! But I suppose we should believe it, despite the youthful gaiety and creative magic of his prose: the internationally bestselling writer has 14 novels and a handful of short stories under his belt, and it’s safe to say he’s one of the most famous contemporary writers in the world. To celebrate his birthday, and as a gift to those of you who hope to be the kind of writer Murakami is when you turn 70, I’ve collected some of his best writing advice below.

Nobel laureate

Nobel laureate  Bahia Amawi, an American speech pathologist of Palestinian descent, was

Bahia Amawi, an American speech pathologist of Palestinian descent, was On the morning of June 10, 1898, Alice Lee marched into the all-male Anatomical Society meeting at Trinity College in Dublin and pulled out a measuring instrument. She then began to take stock of all 35 of the consenting society members’ heads. Lee ranked their skulls from largest to smallest to find that—lo and behold—some of the most well-regarded intellects in their field turned out to possess rather small, unremarkable skulls. This posed a problem, since these anatomists believed that cranial capacity determined intelligence. There were two possibilities: Either these men weren’t as smart as they thought they were, or the size of their skulls had nothing to do with their intelligence.

On the morning of June 10, 1898, Alice Lee marched into the all-male Anatomical Society meeting at Trinity College in Dublin and pulled out a measuring instrument. She then began to take stock of all 35 of the consenting society members’ heads. Lee ranked their skulls from largest to smallest to find that—lo and behold—some of the most well-regarded intellects in their field turned out to possess rather small, unremarkable skulls. This posed a problem, since these anatomists believed that cranial capacity determined intelligence. There were two possibilities: Either these men weren’t as smart as they thought they were, or the size of their skulls had nothing to do with their intelligence. Global warming has heated the oceans by the equivalent of one atomic bomb explosion per second for the past 150 years, according to analysis of new research.

Global warming has heated the oceans by the equivalent of one atomic bomb explosion per second for the past 150 years, according to analysis of new research. Over the last decade, I’ve been asking myself a couple of closely related questions. First, what explains the incredible growth in what we might call urban-rural polarization? What explains the fact that voting behavior has become so highly correlated with population density over time? This is something that’s happened not just in the United States, but also in a number of other industrialized countries. Secondly, what are the implications of this polarization for who wins and loses and whose policy agenda gets put into place?

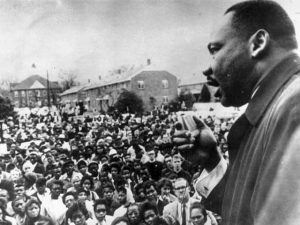

Over the last decade, I’ve been asking myself a couple of closely related questions. First, what explains the incredible growth in what we might call urban-rural polarization? What explains the fact that voting behavior has become so highly correlated with population density over time? This is something that’s happened not just in the United States, but also in a number of other industrialized countries. Secondly, what are the implications of this polarization for who wins and loses and whose policy agenda gets put into place? King was not the empty symbol Reagan and others claimed he was. He was a revolutionary, if one committed to nonviolence. But nonviolence does not exhaust his philosophy. As political theorist Brandon M. Terry puts it, King was not only an icon, but “a vital political thinker.” A half a century ago, Terry argues, King theorized the foundations of racism in a way that vastly surpasses the fashionable contemporary ideologies that “treat racism as near-immutable and overstate its explanatory effects.” As Terry points out, King understood that the racial question was overdetermined by wage stagnation, the declining power of organized labor, and the expulsion of workers from employment by automation. King had come to believe that transforming this structural injustice could only be achieved through mass civil disobedience.

King was not the empty symbol Reagan and others claimed he was. He was a revolutionary, if one committed to nonviolence. But nonviolence does not exhaust his philosophy. As political theorist Brandon M. Terry puts it, King was not only an icon, but “a vital political thinker.” A half a century ago, Terry argues, King theorized the foundations of racism in a way that vastly surpasses the fashionable contemporary ideologies that “treat racism as near-immutable and overstate its explanatory effects.” As Terry points out, King understood that the racial question was overdetermined by wage stagnation, the declining power of organized labor, and the expulsion of workers from employment by automation. King had come to believe that transforming this structural injustice could only be achieved through mass civil disobedience. David Wojnarowicz did not write dark fantasy. He wrote real life. In The Waterfront Journals he brilliantly captures electric tales from the mouths of strangers, those he described as “junkies, prostitutes, male hustlers, truck drivers, hobos, young outlaws, runaway kids, criminal types”, whose lives echo his own ostracized existence. He was thirteen when he was first paid for sex and sixteen when he started “turning tricks” regularly. His mother kicked him out of the house. By the time Wojnarowicz came out to friends in New York, he was in his early twenties. He was on the cusp of finding his voice as a writer and his confidence as an artist. It was the mid-1970s.

David Wojnarowicz did not write dark fantasy. He wrote real life. In The Waterfront Journals he brilliantly captures electric tales from the mouths of strangers, those he described as “junkies, prostitutes, male hustlers, truck drivers, hobos, young outlaws, runaway kids, criminal types”, whose lives echo his own ostracized existence. He was thirteen when he was first paid for sex and sixteen when he started “turning tricks” regularly. His mother kicked him out of the house. By the time Wojnarowicz came out to friends in New York, he was in his early twenties. He was on the cusp of finding his voice as a writer and his confidence as an artist. It was the mid-1970s.  When a sentence isn’t right, I feel it immediately in my back. I’ve said this before. Sometimes I can’t type fast enough to keep up with my thoughts and a specific word disappears from my train of thought forever. Sometimes my body has enough energy to take me to a translation workshop at a friend’s home and my translation is changed for it. Sometimes my body is tired from my day job and I work half as quickly as I used to. Sometimes my body catches cold and my brain muddles words on the page. Once I had a translation deadline to meet but I had just had my tonsils removed and could barely make out the page through the muck of medication. I realized shortly after that I had wound up with something that was half truth and half lie.

When a sentence isn’t right, I feel it immediately in my back. I’ve said this before. Sometimes I can’t type fast enough to keep up with my thoughts and a specific word disappears from my train of thought forever. Sometimes my body has enough energy to take me to a translation workshop at a friend’s home and my translation is changed for it. Sometimes my body is tired from my day job and I work half as quickly as I used to. Sometimes my body catches cold and my brain muddles words on the page. Once I had a translation deadline to meet but I had just had my tonsils removed and could barely make out the page through the muck of medication. I realized shortly after that I had wound up with something that was half truth and half lie. By her own account, writing wasn’t easy for Francine du Plessix Gray, who died last Sunday at the age of eighty-eight. As she told Regina Weinreich in her 1987

By her own account, writing wasn’t easy for Francine du Plessix Gray, who died last Sunday at the age of eighty-eight. As she told Regina Weinreich in her 1987