Zachary Fine at The Paris Review:

The wonder of Harding is that her performances suggest another language of the face. Her many faces fall between the cracks of recognizable emotions and rarely seem to express turmoil or the felt sentiment buried in the songs. Instead, they supplement the music. She employs her face to present a carefully steered choreography, disjoined from the meanings of words and yet fused to the melodies, driving them into stray and unpredictable emotional registers.

The wonder of Harding is that her performances suggest another language of the face. Her many faces fall between the cracks of recognizable emotions and rarely seem to express turmoil or the felt sentiment buried in the songs. Instead, they supplement the music. She employs her face to present a carefully steered choreography, disjoined from the meanings of words and yet fused to the melodies, driving them into stray and unpredictable emotional registers.

I went to see Harding perform live for the first time in April at Rough Trade, a block from the Brooklyn waterfront. I spent most of the performance slack-jawed. I forgot I was holding a drink for thirty minutes. I’ve been riveted by other faces—faces of musicians like Benjamin Clementine and actors like Gottfried John—but Harding was so unregenerately weird on stage that I felt scalded. The terror-struck eyes, the toothy grimace, the wry smiles, the unswerving conviction and cool—I had never seen a face moved, or composed, like this.

more here.

‘When I came

‘When I came In April 1949, the poet

In April 1949, the poet  In two essays,

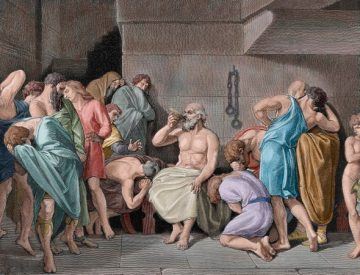

In two essays, Justin E. H. Smith: I am a historian of philosophy who takes seriously the categories of the people whom I study. That is, I try to understand philosophy the way they understood it, rather than the way we understand it. In particular, this means I take seriously the notion that until sometime in the 18th century—maybe even into the 19th century—there was a category that no longer exists called ‘natural philosophy’, which was supplanted by the category of science over the course of the 19th century.

Justin E. H. Smith: I am a historian of philosophy who takes seriously the categories of the people whom I study. That is, I try to understand philosophy the way they understood it, rather than the way we understand it. In particular, this means I take seriously the notion that until sometime in the 18th century—maybe even into the 19th century—there was a category that no longer exists called ‘natural philosophy’, which was supplanted by the category of science over the course of the 19th century. Legend of the Holy Drinker introduces viewers to Olmi’s mature understanding of the economy of grace and the price of salvation. Adapted from a novella by Austrian writer Joseph Roth, the film tells the tragic story of Andreas, a down-and-out middle-aged man living under the bridges of modern Paris. The plot unfolds like a medieval hagiography, replete with chance encounters and sudden (often comical) twists of fortune. Events are set in motion by the unbidden appearance of a kind stranger, a recent convert to Catholicism and devotee of St. Thérèse of Lisieux, who offers Andreas the handsome sum of two hundred francs to help him get back on his feet. There’s a catch, though; the stranger gently requests that Andreas eventually return the money as a holy offering before the saint’s statue, housed in the Church of Sainte-Marie des Batignolles. Andreas, “a man of honor,” readily agrees. But week after week Andreas fails to fulfill his vow, as a series of old acquaintances (and copious carafes of wine) prevent him from making his way to Mass every Sunday.

Legend of the Holy Drinker introduces viewers to Olmi’s mature understanding of the economy of grace and the price of salvation. Adapted from a novella by Austrian writer Joseph Roth, the film tells the tragic story of Andreas, a down-and-out middle-aged man living under the bridges of modern Paris. The plot unfolds like a medieval hagiography, replete with chance encounters and sudden (often comical) twists of fortune. Events are set in motion by the unbidden appearance of a kind stranger, a recent convert to Catholicism and devotee of St. Thérèse of Lisieux, who offers Andreas the handsome sum of two hundred francs to help him get back on his feet. There’s a catch, though; the stranger gently requests that Andreas eventually return the money as a holy offering before the saint’s statue, housed in the Church of Sainte-Marie des Batignolles. Andreas, “a man of honor,” readily agrees. But week after week Andreas fails to fulfill his vow, as a series of old acquaintances (and copious carafes of wine) prevent him from making his way to Mass every Sunday. What made Reed’s songs special went beyond his notorious obsession with decadence, his caustic dry wit, and his sneaky romantic vulnerability. He was also one of the most literate of musicians and wasn’t shy about making his literary influences known. As a college kid, he was mentored by the brilliantly mad poet and critic

What made Reed’s songs special went beyond his notorious obsession with decadence, his caustic dry wit, and his sneaky romantic vulnerability. He was also one of the most literate of musicians and wasn’t shy about making his literary influences known. As a college kid, he was mentored by the brilliantly mad poet and critic  Stewart is particularly good on the double-edged quality of the miniature. She grasps that the doll’s house is both paradise and cloister, for example, that it “represents a particular form of interiority, an interiority which the subject experiences as its sanctuary (fantasy) and prison”. She argues that the miniature always presents something that has already been lost, that you can never quite touch: “a world whose anteriority is always absolute, and whose profound interiority is therefore always unrecoverable”. While it can be tempting to focus on miniatures as fulfilments of fantasy, as Garfield does, Stewart asks us to read them as promises that are perpetually broken, as sites of unresolved longing. Miniatures are more like excursions than journeys, she argues, because you always have to come back from the fantasy. You can never stay for good. I’d argue that you can’t even really go in the first place: as with the shrinking man of Bekonscot, entering the miniature landscape means losing the very thing that makes it magical.

Stewart is particularly good on the double-edged quality of the miniature. She grasps that the doll’s house is both paradise and cloister, for example, that it “represents a particular form of interiority, an interiority which the subject experiences as its sanctuary (fantasy) and prison”. She argues that the miniature always presents something that has already been lost, that you can never quite touch: “a world whose anteriority is always absolute, and whose profound interiority is therefore always unrecoverable”. While it can be tempting to focus on miniatures as fulfilments of fantasy, as Garfield does, Stewart asks us to read them as promises that are perpetually broken, as sites of unresolved longing. Miniatures are more like excursions than journeys, she argues, because you always have to come back from the fantasy. You can never stay for good. I’d argue that you can’t even really go in the first place: as with the shrinking man of Bekonscot, entering the miniature landscape means losing the very thing that makes it magical. If chocolate

If chocolate  Today the alkaline desert is quiet. The roar of techno music and flamethrowers has been replaced with the soft clink of rakes and trash cans. Thousands of people put aside their hangovers to methodically clean the desert. After a dedicated communal cleaning, Burning Man, one of the largest arts events in the world, spanning seven days and involving over 70,000 participants, leaves not a single wrapper on the desert. Among the swarm of salt-crusted denizens of this ephemeral city (known as Burners) is us: a scientist who studies cooperation, an industrial designer, and a Silicon Valley security CEO. Among the dismantled rigs, lifeless pyrotechnics, and bowed heads of Burners absorbed in cleaning, we are here trying to answer a simple question: How, after so many years, could Burning Man throw an event of such chaos, and yet leave the desert without a trace? What leads thousands of people in such an extreme environment to consistently engage in cooperative behavior at a scale seldom seen in society?

Today the alkaline desert is quiet. The roar of techno music and flamethrowers has been replaced with the soft clink of rakes and trash cans. Thousands of people put aside their hangovers to methodically clean the desert. After a dedicated communal cleaning, Burning Man, one of the largest arts events in the world, spanning seven days and involving over 70,000 participants, leaves not a single wrapper on the desert. Among the swarm of salt-crusted denizens of this ephemeral city (known as Burners) is us: a scientist who studies cooperation, an industrial designer, and a Silicon Valley security CEO. Among the dismantled rigs, lifeless pyrotechnics, and bowed heads of Burners absorbed in cleaning, we are here trying to answer a simple question: How, after so many years, could Burning Man throw an event of such chaos, and yet leave the desert without a trace? What leads thousands of people in such an extreme environment to consistently engage in cooperative behavior at a scale seldom seen in society? You are not Proust. Do not write long sentences. If they come into your head, write them, but then break them down. Do not be afraid to repeat the subject twice, and stay away from too many pronouns and subordinate clauses. Do not write,

You are not Proust. Do not write long sentences. If they come into your head, write them, but then break them down. Do not be afraid to repeat the subject twice, and stay away from too many pronouns and subordinate clauses. Do not write, Scientists at the

Scientists at the

At the heart of Ong’s analysis is the understanding that each major transition in media technology — that is, in the means of communication — transformed or restructured human consciousness and human society. “Technologies are not mere exterior aids,” Ong explains, “but also interior transformations of consciousness, and never more than when they affect the word.” Literate society was not simply the old society of primary orality with the added advantage of writing, but in many respects a new society. The advent of electronic media was similarly consequential, inaugurating what we think of as the age of mass media in the twentieth century. Now we find ourselves thrust into an era dominated by the effects of digital media. We can’t yet know the full ramifications of this transition, but, taking a cue from some of Ong’s insights, we can begin to make some pertinent observations, particularly with respect to the character of digital discourse.

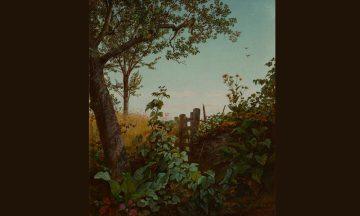

At the heart of Ong’s analysis is the understanding that each major transition in media technology — that is, in the means of communication — transformed or restructured human consciousness and human society. “Technologies are not mere exterior aids,” Ong explains, “but also interior transformations of consciousness, and never more than when they affect the word.” Literate society was not simply the old society of primary orality with the added advantage of writing, but in many respects a new society. The advent of electronic media was similarly consequential, inaugurating what we think of as the age of mass media in the twentieth century. Now we find ourselves thrust into an era dominated by the effects of digital media. We can’t yet know the full ramifications of this transition, but, taking a cue from some of Ong’s insights, we can begin to make some pertinent observations, particularly with respect to the character of digital discourse. The painting that kicked it all off, Ruskin’s own Fragment of the Alps, goes a long way towards explaining the intermingling of spirituality and scientific exactitude found in the best of the American Pre-Raphaelites’ works. Shuttled around America in a touring exhibition in the year 1857, the small canvas is a fantasia of vivid yellows and saturated purples, yet this almost surreal medley stems from no more mystical source than Ruskin’s hidebound attention to the play of light on stone. As the exhibition notes make clear, the careful delineation of the natural environment was a profoundly moral act for Ruskin. Detail became a form of prayer, a sort of thanksgiving for and hymn to God’s creation. The delicate plexing of boughs in Charles Herbert Moore’s Pine Tree, from 1868, are a perfect non-Ruskinian example of this drive — the detail is so fine that the tree seems to be melting upward, the fine pen markings gradually being blown away by the wind.

The painting that kicked it all off, Ruskin’s own Fragment of the Alps, goes a long way towards explaining the intermingling of spirituality and scientific exactitude found in the best of the American Pre-Raphaelites’ works. Shuttled around America in a touring exhibition in the year 1857, the small canvas is a fantasia of vivid yellows and saturated purples, yet this almost surreal medley stems from no more mystical source than Ruskin’s hidebound attention to the play of light on stone. As the exhibition notes make clear, the careful delineation of the natural environment was a profoundly moral act for Ruskin. Detail became a form of prayer, a sort of thanksgiving for and hymn to God’s creation. The delicate plexing of boughs in Charles Herbert Moore’s Pine Tree, from 1868, are a perfect non-Ruskinian example of this drive — the detail is so fine that the tree seems to be melting upward, the fine pen markings gradually being blown away by the wind. Tate’s final work will lodge him permanently in the landscape of American poetry, but, like Dickinson, he will always also be a local phenomenon. In 2004, he published a poem, “Of Whom Am I Afraid?,” about encountering “an old grizzled farmer” at the supply store. They strike up a conversation about Dickinson’s poetry. (It may seem unlikely, or “Surreal,” but Amherst has always had its share of literary farmers.) These two men discuss Dickinson’s toughness; then the farmer, testing Tate’s own mettle, slaps him across the face. Somehow this is a form of homage, and Tate commemorates the occasion by buying “some ice tongs . . . for which I had no earthly use.” They wind up, instead, in a poem. It’s that higher utility that Tate always sought.

Tate’s final work will lodge him permanently in the landscape of American poetry, but, like Dickinson, he will always also be a local phenomenon. In 2004, he published a poem, “Of Whom Am I Afraid?,” about encountering “an old grizzled farmer” at the supply store. They strike up a conversation about Dickinson’s poetry. (It may seem unlikely, or “Surreal,” but Amherst has always had its share of literary farmers.) These two men discuss Dickinson’s toughness; then the farmer, testing Tate’s own mettle, slaps him across the face. Somehow this is a form of homage, and Tate commemorates the occasion by buying “some ice tongs . . . for which I had no earthly use.” They wind up, instead, in a poem. It’s that higher utility that Tate always sought. There never seems to be enough time to accomplish all the things we must do. Life gets busier and busier. But what does all that busy-ness add to our lives? Mainstream culture tells us that being busy is a virtue, so we want to be busy even if we complain about it. It means we’re productive and have purpose. Ideas like “time is money” and “idle hands are the devil’s workshop” have helped to define our culture. Both ideas work in concert with the global capitalist economy, which depends on keeping us busy in order to increase productivity, expand markets, and encourage hyper-consumption. Busy-ness also helps to keep us from questioning the assumptions and values that drive busy-ness itself. Busy-ness is part of a broader set of structures that limit our choices and our ability to feel satisfied. What we call the “

There never seems to be enough time to accomplish all the things we must do. Life gets busier and busier. But what does all that busy-ness add to our lives? Mainstream culture tells us that being busy is a virtue, so we want to be busy even if we complain about it. It means we’re productive and have purpose. Ideas like “time is money” and “idle hands are the devil’s workshop” have helped to define our culture. Both ideas work in concert with the global capitalist economy, which depends on keeping us busy in order to increase productivity, expand markets, and encourage hyper-consumption. Busy-ness also helps to keep us from questioning the assumptions and values that drive busy-ness itself. Busy-ness is part of a broader set of structures that limit our choices and our ability to feel satisfied. What we call the “