Robert Reich in The Guardian:

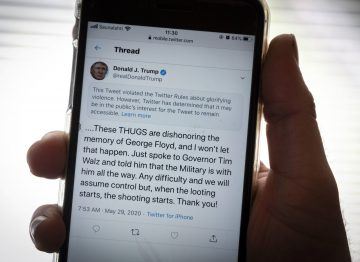

You’d be forgiven if you hadn’t noticed. His verbal bombshells are louder than ever, but Donald J Trump is no longer president of the United States. By having no constructive response to any of the monumental crises now convulsing America, Trump has abdicated his office. He is not governing. He’s golfing, watching cable TV and tweeting. How has Trump responded to the widespread unrest following the murder in Minneapolis of George Floyd, a black man who died after a white police officer knelt on his neck for minutes as he was handcuffed on the ground? Trump called the protesters “thugs” and threatened to have them shot. “When the looting starts, the shooting starts,” he tweeted, parroting a former Miami police chief whose words spurred race riots in the late 1960s. On Saturday, he gloated about “the most vicious dogs, and most ominous weapons” awaiting protesters outside the White House, should they ever break through Secret Service lines.

You’d be forgiven if you hadn’t noticed. His verbal bombshells are louder than ever, but Donald J Trump is no longer president of the United States. By having no constructive response to any of the monumental crises now convulsing America, Trump has abdicated his office. He is not governing. He’s golfing, watching cable TV and tweeting. How has Trump responded to the widespread unrest following the murder in Minneapolis of George Floyd, a black man who died after a white police officer knelt on his neck for minutes as he was handcuffed on the ground? Trump called the protesters “thugs” and threatened to have them shot. “When the looting starts, the shooting starts,” he tweeted, parroting a former Miami police chief whose words spurred race riots in the late 1960s. On Saturday, he gloated about “the most vicious dogs, and most ominous weapons” awaiting protesters outside the White House, should they ever break through Secret Service lines.

Trump’s response to the last three ghastly months of mounting disease and death has been just as heedless. Since claiming Covid-19 was a “Democratic hoax” and muzzling public health officials, he has punted management of the coronavirus to the states. Governors have had to find ventilators to keep patients alive and protective equipment for hospital and other essential workers who lack it, often bidding against each other. They have had to decide how, when and where to reopen their economies.

…In reality, Donald Trump doesn’t run the government of the United States. He doesn’t manage anything. He doesn’t organize anyone. He doesn’t administer or oversee or supervise. He doesn’t read memos. He hates meetings. He has no patience for briefings. His White House is in perpetual chaos. His advisers aren’t truth-tellers. They’re toadies, lackeys, sycophants and relatives. Since moving into the Oval Office in January 2017, Trump hasn’t shown an ounce of interest in governing. He obsesses only about himself. But it has taken the present set of crises to reveal the depths of his self-absorbed abdication – his utter contempt for his job, his total repudiation of his office. Trump’s nonfeasance goes far beyond an absence of leadership or inattention to traditional norms and roles. In a time of national trauma, he has relinquished the core duties and responsibilities of the presidency.

He is no longer president. The sooner we stop treating him as if he were, the better.

More here.

Peter E. Gordon and Sam Moyn debate if and how the “fascism” label is appropriate for Orbán, Erdoğan, Modi, or Trump, over at the NY Review of Books.

Peter E. Gordon and Sam Moyn debate if and how the “fascism” label is appropriate for Orbán, Erdoğan, Modi, or Trump, over at the NY Review of Books.  Stephen Nash in Sapiens:

Stephen Nash in Sapiens: O

O

Christian Barry and Seth Lazar in Ethics and International Affairs:

Christian Barry and Seth Lazar in Ethics and International Affairs: To untangle the Omegaverse fight, it helps to understand its origins in a parallel literary universe — the vast, unruly, diverse, exuberant and often pornographic world of fan fiction.

To untangle the Omegaverse fight, it helps to understand its origins in a parallel literary universe — the vast, unruly, diverse, exuberant and often pornographic world of fan fiction. Physicist Richard Feynman had the following advice for those interested in science: “So I hope you can accept Nature as She is—absurd.”

Physicist Richard Feynman had the following advice for those interested in science: “So I hope you can accept Nature as She is—absurd.” President Trump told reporters Friday evening that he didn’t know the racially charged history behind the phrase “when the looting starts, the shooting starts.” Trump tweeted the phrase Friday morning in reference to the

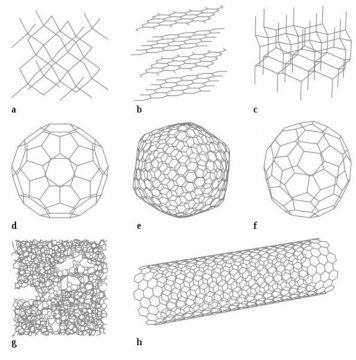

President Trump told reporters Friday evening that he didn’t know the racially charged history behind the phrase “when the looting starts, the shooting starts.” Trump tweeted the phrase Friday morning in reference to the Emergence occurs when there is a conceptual discontinuity between two descriptions targeting the same phenomenon. This does not mean that emergence is a purely subjective phenomenon — only that scientific ‘double coverage’ may be a good place to look for emergent phenomena.

Emergence occurs when there is a conceptual discontinuity between two descriptions targeting the same phenomenon. This does not mean that emergence is a purely subjective phenomenon — only that scientific ‘double coverage’ may be a good place to look for emergent phenomena. Respiratory infections occur through the transmission of virus-containing droplets (>5 to 10 μm) and aerosols (≤5 μm) exhaled from infected individuals during breathing, speaking, coughing, and sneezing. Traditional respiratory disease control measures are designed to reduce transmission by droplets produced in the sneezes and coughs of infected individuals. However, a large proportion of the spread of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) appears to be occurring through airborne transmission of aerosols produced by asymptomatic individuals during breathing and speaking (

Respiratory infections occur through the transmission of virus-containing droplets (>5 to 10 μm) and aerosols (≤5 μm) exhaled from infected individuals during breathing, speaking, coughing, and sneezing. Traditional respiratory disease control measures are designed to reduce transmission by droplets produced in the sneezes and coughs of infected individuals. However, a large proportion of the spread of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) appears to be occurring through airborne transmission of aerosols produced by asymptomatic individuals during breathing and speaking ( The amazing thing about Faiz Ahmed Faiz is that you can never leave him behind. Witness how he emerged in the midst of the recent protests in India with ‘Hum Dekhenge’ being sung in half a dozen languages to the point where flummoxed authorities were forced to treat a man, dead for a good 35 years, as a threat to national security.

The amazing thing about Faiz Ahmed Faiz is that you can never leave him behind. Witness how he emerged in the midst of the recent protests in India with ‘Hum Dekhenge’ being sung in half a dozen languages to the point where flummoxed authorities were forced to treat a man, dead for a good 35 years, as a threat to national security. For his part, however, Foucault moved on, somewhat singularly among his generation. Rather than staying in the world of words, in the 1970s he shifted his philosophical attention to power, an idea that promises to help explain how words, or anything else for that matter, come to give things the order that they have. But Foucault’s lasting importance is not in his having found some new master-concept that can explain all the others. Power, in Foucault, is not another philosophical godhead. For Foucault’s most crucial claim about power is that we must refuse to treat it as philosophers have always treated their central concepts, namely as a unitary and homogenous thing that is so at home with itself that it can explain everything else.

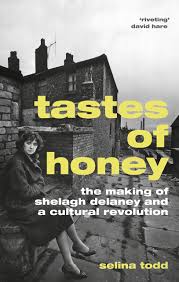

For his part, however, Foucault moved on, somewhat singularly among his generation. Rather than staying in the world of words, in the 1970s he shifted his philosophical attention to power, an idea that promises to help explain how words, or anything else for that matter, come to give things the order that they have. But Foucault’s lasting importance is not in his having found some new master-concept that can explain all the others. Power, in Foucault, is not another philosophical godhead. For Foucault’s most crucial claim about power is that we must refuse to treat it as philosophers have always treated their central concepts, namely as a unitary and homogenous thing that is so at home with itself that it can explain everything else. Selina Todd’s biography of Delaney does two things well. It helps us understand how someone the press insisted on calling a ‘Salford teenager’ was able to create this remarkable work – and it shows how hard the people who brought the play to stage and screen worked to shift the spotlight away from that intense mother-daughter dynamic. There was a script, too, for ‘new writers’ in the late 1950s and 1960s: they were to be young, authentic and, if possible, working class; they were to be masculine, rebellious and shocking. When, in April 1958, Delaney sent her play to Joan Littlewood, the director of the avant-garde Theatre Workshop in East London, she adopted a naive, Northern persona that was more than a little misleading. ‘A fortnight ago I didn’t know the theatre existed,’ she gushed to Littlewood – but then a friend had taken her to see a play and she had discovered ‘something that meant more to me than myself’. She now knew she wanted to write plays, and in two weeks had produced the enclosed ‘epic’. ‘Please can you help me? I’m willing enough to help myself.’ Christened plain ‘Sheila’, she signed the letter ‘Shelagh Delaney’, the name by which she would be known from then on.

Selina Todd’s biography of Delaney does two things well. It helps us understand how someone the press insisted on calling a ‘Salford teenager’ was able to create this remarkable work – and it shows how hard the people who brought the play to stage and screen worked to shift the spotlight away from that intense mother-daughter dynamic. There was a script, too, for ‘new writers’ in the late 1950s and 1960s: they were to be young, authentic and, if possible, working class; they were to be masculine, rebellious and shocking. When, in April 1958, Delaney sent her play to Joan Littlewood, the director of the avant-garde Theatre Workshop in East London, she adopted a naive, Northern persona that was more than a little misleading. ‘A fortnight ago I didn’t know the theatre existed,’ she gushed to Littlewood – but then a friend had taken her to see a play and she had discovered ‘something that meant more to me than myself’. She now knew she wanted to write plays, and in two weeks had produced the enclosed ‘epic’. ‘Please can you help me? I’m willing enough to help myself.’ Christened plain ‘Sheila’, she signed the letter ‘Shelagh Delaney’, the name by which she would be known from then on.