Susan Glasser in The New Yorker:

On Sunday, on Tuesday, and again on Wednesday, President Donald Trump accused the TV talk-show host Joe Scarborough of murder. On Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday, he attacked the integrity of America’s forthcoming “rigged” election. When he woke up on Wednesday, he alleged that the Obama Administration had “spied, in an unprecedented manner, on the Trump Campaign, and beyond, and even on the United States Senate.” By midnight Wednesday, a few hours after the number of U.S. deaths in the coronavirus pandemic officially exceeded a hundred thousand, the President of the United States retweeted a video that says, “the only good Democrat is a dead Democrat.”

On Sunday, on Tuesday, and again on Wednesday, President Donald Trump accused the TV talk-show host Joe Scarborough of murder. On Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday, he attacked the integrity of America’s forthcoming “rigged” election. When he woke up on Wednesday, he alleged that the Obama Administration had “spied, in an unprecedented manner, on the Trump Campaign, and beyond, and even on the United States Senate.” By midnight Wednesday, a few hours after the number of U.S. deaths in the coronavirus pandemic officially exceeded a hundred thousand, the President of the United States retweeted a video that says, “the only good Democrat is a dead Democrat.”

This is not the first time when the tweets emanating from the man in the White House have featured baseless accusations of murder, vote fraud, and his predecessor’s “illegality and corruption.” It’s not even the first time this month. So many of the things that Trump does and says are inconceivable for an American President, and yet he does and says them anyway. The Trump era has been a seemingly endless series of such moments. From the start of his Administration, his tweets have been an open-source intelligence boon, a window directly into the President’s needy id, and a real-time guide to his obsessions and intentions. Misinformation, disinformation, and outright lies were always central to his politics. In recent months, however, his tweeting appears to have taken an even darker, more manic, and more mendacious turn, as Trump struggles to manage the convergence of a massive public-health crisis and a simultaneous economic collapse while running for reëlection. He is tweeting more frequently, and more frantically, as events have closed in on him. Trailing in the polls and desperate to change the subject from the coronavirus, mid-pandemic Trump has a Twitter feed that is meaner, angrier, and more partisan than ever before, as he amplifies conspiracy theories about the “deep state” and media enemies such as Scarborough while seeking to exacerbate divisions in an already divided country.

Strikingly, this dark turn with the President’s tweets comes as he is using his Twitter feed as an even more potent vehicle for telling his Republican followers what to do—and they are listening.

More here.

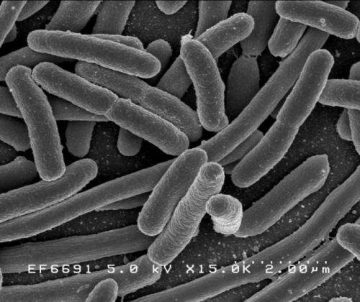

Bacteria have a cunning ability to survive in unfriendly environments. For example, through a complicated series of interactions, they can identify—and then build resistance to—

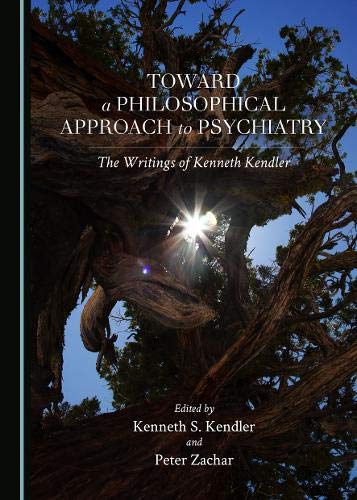

Bacteria have a cunning ability to survive in unfriendly environments. For example, through a complicated series of interactions, they can identify—and then build resistance to— There continues to be an impressive appetite for conceptual and philosophical explorations of psychiatry. The publishing field is now populated by a diverse array of backgrounds and perspectives. The general public seems mostly interested in decrying the medicalization of normal and the transformation of our woes into neatly packaged mental disorders. The academic literature is dominated by philosophers and philosophically-trained professionals; while the intellectual discourse is of high caliber, it unfortunately remains largely inaccessible to mental health professionals and much of the general public, and resultantly it has had little influence outside the academic community. There is also a cohort of individuals with a critical interest in the subject but whose philosophical focus remains stuck on classical critical figures such as Thomas Szasz, Michel Foucault and R.D. Laing, with little engagement with contemporary philosophy of science. The philosophical work of Kenneth Kendler and his various collaborators (John Campbell, Carl Craver, Kenneth Schaffner, Erik Engstrom, Rodrigo Munoz, George Murphy, and Peter Zachar) assembled in a specially curated volume occupies a unique and special position in this contemporary landscape and there is much to be said in its favor.

There continues to be an impressive appetite for conceptual and philosophical explorations of psychiatry. The publishing field is now populated by a diverse array of backgrounds and perspectives. The general public seems mostly interested in decrying the medicalization of normal and the transformation of our woes into neatly packaged mental disorders. The academic literature is dominated by philosophers and philosophically-trained professionals; while the intellectual discourse is of high caliber, it unfortunately remains largely inaccessible to mental health professionals and much of the general public, and resultantly it has had little influence outside the academic community. There is also a cohort of individuals with a critical interest in the subject but whose philosophical focus remains stuck on classical critical figures such as Thomas Szasz, Michel Foucault and R.D. Laing, with little engagement with contemporary philosophy of science. The philosophical work of Kenneth Kendler and his various collaborators (John Campbell, Carl Craver, Kenneth Schaffner, Erik Engstrom, Rodrigo Munoz, George Murphy, and Peter Zachar) assembled in a specially curated volume occupies a unique and special position in this contemporary landscape and there is much to be said in its favor.

What would become known as the CARES Act

What would become known as the CARES Act

Two incidents separated by twelve hours and twelve hundred miles have taken on the appearance of the control and the variable in a grotesque experiment about race in America. On Monday morning, in New York City’s Central Park, a white woman named Amy Cooper called 911 and told the dispatcher that an African-American man was threatening her. The man she was talking about, Christian Cooper, who is no relation, filmed the call on his phone. They were in the Ramble, a part of the park favored by bird-watchers, including Christian Cooper, and he had simply requested that she leash her dog—something that is required in the area. In the video, before making the call, Ms. Cooper warns Mr. Cooper that she is “going to tell them there’s an African-American man threatening my life.” Her needless inclusion of the race of the man she fears serves only to summon the ancient impulse to protect white womanhood from the threats posed by black men. For anyone with a long enough memory or a recent enough viewing of the series “

Two incidents separated by twelve hours and twelve hundred miles have taken on the appearance of the control and the variable in a grotesque experiment about race in America. On Monday morning, in New York City’s Central Park, a white woman named Amy Cooper called 911 and told the dispatcher that an African-American man was threatening her. The man she was talking about, Christian Cooper, who is no relation, filmed the call on his phone. They were in the Ramble, a part of the park favored by bird-watchers, including Christian Cooper, and he had simply requested that she leash her dog—something that is required in the area. In the video, before making the call, Ms. Cooper warns Mr. Cooper that she is “going to tell them there’s an African-American man threatening my life.” Her needless inclusion of the race of the man she fears serves only to summon the ancient impulse to protect white womanhood from the threats posed by black men. For anyone with a long enough memory or a recent enough viewing of the series “ As many countries emerge from lockdowns, researchers are poised to use genome sequencing to avoid an expected second wave of COVID-19 infections. Since the first whole-genome sequence of the new coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, was

As many countries emerge from lockdowns, researchers are poised to use genome sequencing to avoid an expected second wave of COVID-19 infections. Since the first whole-genome sequence of the new coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, was  The combined total of inflation and unemployment used to be known as the “misery index”: Jimmy Carter cited it when he was campaigning in 1976 against Gerald Ford for the presidency. But the index was even higher in 1980, dooming Carter’s re-election bid. Barack Obama reduced the misery index during his two terms of office; indeed of all the Presidents since 1945, only Harry Truman left office with a lower misery index. But that didn’t seem to make voters happy; although Hillary Clinton (Obama’s party successor) won the popular vote, Donald Trump took enough key states to be elected. Similarly in 2016, British inflation was low and unemployment had been falling for years, yet voter anger resulted in Britain voting to leave the EU.

The combined total of inflation and unemployment used to be known as the “misery index”: Jimmy Carter cited it when he was campaigning in 1976 against Gerald Ford for the presidency. But the index was even higher in 1980, dooming Carter’s re-election bid. Barack Obama reduced the misery index during his two terms of office; indeed of all the Presidents since 1945, only Harry Truman left office with a lower misery index. But that didn’t seem to make voters happy; although Hillary Clinton (Obama’s party successor) won the popular vote, Donald Trump took enough key states to be elected. Similarly in 2016, British inflation was low and unemployment had been falling for years, yet voter anger resulted in Britain voting to leave the EU. Julia Wellner and other crew members for this year’s Thwaites Glacier Offshore Research Project stepped onto the deck of the research vessel/icebreaker (RV/IB) Nathaniel B. Palmer in January, leaving from a crowded pier in Punta Arenas, Chile, and sailing to west coast of Antarctica.

Julia Wellner and other crew members for this year’s Thwaites Glacier Offshore Research Project stepped onto the deck of the research vessel/icebreaker (RV/IB) Nathaniel B. Palmer in January, leaving from a crowded pier in Punta Arenas, Chile, and sailing to west coast of Antarctica. When in mid-March “

When in mid-March “ Adam Horovitz was born in Manhattan, in 1966, and raised there by his mother, the artist Doris Keefe. His father, the playwright Israel Horovitz, left the family in 1969. New York in the seventies was wild and lawless, which suited a young person searching for a tribe. As a teen-ager, Horovitz played in a New York punk band called the Young and the Useless. There was no imaginable future in music for him. It was just a way to pass the time, an excuse to hang out and meet people who were into the same things as he was. The Young and the Useless would often play shows with another punk band called the Beastie Boys, which consisted at the time of Horovitz’s friends Adam Yauch, Michael Diamond, John Berry, and Kate Schellenbach. In 1982, as the Beastie Boys were moving from punk to hip-hop, Berry left the band, and Horovitz, who was sixteen, replaced him. A couple of years later, they asked Schellenbach to leave, as they pursued, in Horovitz’s words, a new “tough-rapper-guy identity.”

Adam Horovitz was born in Manhattan, in 1966, and raised there by his mother, the artist Doris Keefe. His father, the playwright Israel Horovitz, left the family in 1969. New York in the seventies was wild and lawless, which suited a young person searching for a tribe. As a teen-ager, Horovitz played in a New York punk band called the Young and the Useless. There was no imaginable future in music for him. It was just a way to pass the time, an excuse to hang out and meet people who were into the same things as he was. The Young and the Useless would often play shows with another punk band called the Beastie Boys, which consisted at the time of Horovitz’s friends Adam Yauch, Michael Diamond, John Berry, and Kate Schellenbach. In 1982, as the Beastie Boys were moving from punk to hip-hop, Berry left the band, and Horovitz, who was sixteen, replaced him. A couple of years later, they asked Schellenbach to leave, as they pursued, in Horovitz’s words, a new “tough-rapper-guy identity.”