Stephen Nash in Sapiens:

Stephen Nash in Sapiens:

In October of last year, I found myself with my family in the heart of a sacred forest of the Mijikenda people of Kenya. One of the elders there told me that seven funerary statues had been stolen from his homestead in the preceding decades. He didn’t cry; he didn’t get angry. He just stared at the ground with a glazed look in his eyes. It was the look of a man who had come to terms with his loss but who had not forgotten the harm or gotten over the pain. It was overwhelming to hear his story, and I’ll never forget that moment.

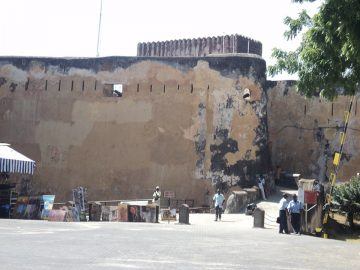

Sadly, 30 similar statues had been held since 1990 at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science (DMNS), where I work. It had taken me more than a decade to get them shipped back to Kenya. Now I had the chance to visit them at the Fort Jesus Museum in Mombasa; it was amazing to see them again, so close to their home, where they belong.

This is the story of their decadelong journey.

Most people in modern society enjoy the right to decide what happens to their bodies, as well as those of their loved ones, when they die. As Chip Colwell, my former DMNS colleague and editor-in-chief of SAPIENS, noted so eloquently in his book Plundered Skulls and Stolen Spirits, this has not been the case for Indigenous populations under colonial rule, with tragic effects. The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) of 1990 helped to rectify this situation in the United States by providing a legal framework under which federally recognized tribes may formally request the return of their ancestors’ remains, sacred objects, and other materials. NAGPRA has no bearing on international repatriations, however.

More here.