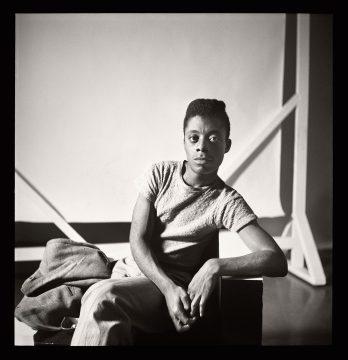

Chase Quinn in The Guardian:

How does it feel to be black in America right now? First, I wonder, do I capitalize the “B”? Is that grammatically correct? More to the point, as an element of style, a choice, does it prove something to you or to me if I don’t? I confess I don’t know any more. These are the petty games that play on my mind as a black American. I cannot speak for all black people, of course. We are not a monolith; you seem to understand this by now. I can only speak for myself – as a black writer. That experience, at least, I know. Instead of worrying about the white man who might murder me in my own home, or on my morning run, what preys on me in the night is how I constructed the sentence as I replay the day, if it was adequately punctuated in its disavowal of racist oppression.

How does it feel to be black in America right now? First, I wonder, do I capitalize the “B”? Is that grammatically correct? More to the point, as an element of style, a choice, does it prove something to you or to me if I don’t? I confess I don’t know any more. These are the petty games that play on my mind as a black American. I cannot speak for all black people, of course. We are not a monolith; you seem to understand this by now. I can only speak for myself – as a black writer. That experience, at least, I know. Instead of worrying about the white man who might murder me in my own home, or on my morning run, what preys on me in the night is how I constructed the sentence as I replay the day, if it was adequately punctuated in its disavowal of racist oppression.

You see, I was raised in the house of “you can be whatever you want – with hard work,” the appendix like the slamming shut of a piano. I’m 33 years old. I was taught to be proud of being black, and I am. There are few things of which I am prouder. No dangling prepositions here, just the facts. I have earned the straight As. I have stayed past the bell. I have pushed myself to raise my hand, to venture an answer, even when I wasn’t sure I understood the question. I was taught that fear, like racial oppression or homophobia, was to be overcome. Walk with your head held high, my mother taught me. Let them admire and be transformed by your strength, by your unassailable conduct. Play it again, Sam – the one that says things will be different in the next life. They’ll look at me and think how far we’ve come. But will they, actually?

I heard from my cousin the other day. She texted me a video of her son on the news. He was protesting in front of the White House. To the newscaster, he said: “They’re not hearing us.” His friend added: “When you talk, it’s just words to them.” Just words indeed. I thought to myself: I should be proud. Proud that my little cousin, who also survived a school shooting just a few years ago, is out on the street, marching, standing up for what is right. Proud of his mother too, for raising a young black man and sending him to college, as a single mother. But instead I felt sorry, like I’d failed him. Like we all had.

More here.

Mona Ali in The Political Quarterly:

Mona Ali in The Political Quarterly: James Baldwin in The New Yorker:

James Baldwin in The New Yorker: Andrew Hui in Aeon:

Andrew Hui in Aeon: Quinn Slobodian in The Guardian:

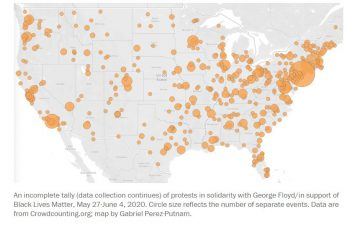

Quinn Slobodian in The Guardian: Lara Putnam, Erica Chenoweth and Jeremy Pressman over at the Monkey Cage:

Lara Putnam, Erica Chenoweth and Jeremy Pressman over at the Monkey Cage: A

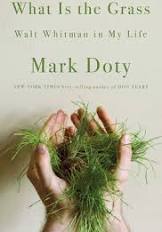

A Academic critics of Dryden or Pope were not in the habit, the last time I checked, of interspersing their monographs with reminiscences of sex clubs in Manhattan. An affectionate excursus on that subject in Mark Doty’s What is the Grass announces that this is no ordinary piece of literary criticism. ‘And your very flesh shall be a great poem,’ wrote Doty’s subject, Walt Whitman, who, one suspects, wouldn’t have minded a bit. Perhaps best known for his 1993 collection My Alexandria, prompted by the AIDS pandemic, Doty is one of the most compelling modern singers of ‘the body electric’ and in What is the Grass he has produced an elegant meditation on the great founding father of American poetry. Not only did Whitman’s example fire up the democratic modern lyrics of W C Williams and Allen Ginsberg; it also licensed poets to place themselves centre stage in their prose, from Adrienne Rich in What is Found There to Susan Howe in her prose-poetry hybrids. It is a licence that Doty seizes on greedily.

Academic critics of Dryden or Pope were not in the habit, the last time I checked, of interspersing their monographs with reminiscences of sex clubs in Manhattan. An affectionate excursus on that subject in Mark Doty’s What is the Grass announces that this is no ordinary piece of literary criticism. ‘And your very flesh shall be a great poem,’ wrote Doty’s subject, Walt Whitman, who, one suspects, wouldn’t have minded a bit. Perhaps best known for his 1993 collection My Alexandria, prompted by the AIDS pandemic, Doty is one of the most compelling modern singers of ‘the body electric’ and in What is the Grass he has produced an elegant meditation on the great founding father of American poetry. Not only did Whitman’s example fire up the democratic modern lyrics of W C Williams and Allen Ginsberg; it also licensed poets to place themselves centre stage in their prose, from Adrienne Rich in What is Found There to Susan Howe in her prose-poetry hybrids. It is a licence that Doty seizes on greedily. Before Italy became a nation, it was made up of a collection of city-states governed by un’autorità superior, in the form of a powerful noble family or a bishop. Siena was an exception in that it favoured civic rule. This partly accounts for the unique character of its art. It produced Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s The Allegory of Good and Bad Government, a series of frescos housed in the Palazzo Pubblico, the civic heart of the city. It is one of the earliest and most significant secular paintings we have. If civic rule were a church, this would be its altarpiece. Siena also imbued its artists with a rare and humanist curiosity that, even in their depictions of religious scenes, involved them in meditations on human psychology and ideas.

Before Italy became a nation, it was made up of a collection of city-states governed by un’autorità superior, in the form of a powerful noble family or a bishop. Siena was an exception in that it favoured civic rule. This partly accounts for the unique character of its art. It produced Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s The Allegory of Good and Bad Government, a series of frescos housed in the Palazzo Pubblico, the civic heart of the city. It is one of the earliest and most significant secular paintings we have. If civic rule were a church, this would be its altarpiece. Siena also imbued its artists with a rare and humanist curiosity that, even in their depictions of religious scenes, involved them in meditations on human psychology and ideas.

In 1916, the 26-year-old Agatha Christie finished writing her first detective novel at Dartmoor, a quiet upland in Devon, UK, known for its beautiful granite hilltops. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle had published The Hound of the Baskervilles, in 1902, which would become one of the most widely read Sherlock Holmes adventures—and the story was set in this same corner of the world, Dartmoor.

In 1916, the 26-year-old Agatha Christie finished writing her first detective novel at Dartmoor, a quiet upland in Devon, UK, known for its beautiful granite hilltops. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle had published The Hound of the Baskervilles, in 1902, which would become one of the most widely read Sherlock Holmes adventures—and the story was set in this same corner of the world, Dartmoor. The

The  As it turns out, humans are wired to worry. Our brains are continually imagining futures that will meet our needs and things that could stand in the way of them. And sometimes any of those needs may be in conflict with each other.

As it turns out, humans are wired to worry. Our brains are continually imagining futures that will meet our needs and things that could stand in the way of them. And sometimes any of those needs may be in conflict with each other. In the opening lines of Cold Warriors, Duncan White notes that “between February and May 1955, a group covertly funded by the Central Intelligence Agency launched a secret weapon into Communist territory”: balloons carrying copies of George Orwell’s

In the opening lines of Cold Warriors, Duncan White notes that “between February and May 1955, a group covertly funded by the Central Intelligence Agency launched a secret weapon into Communist territory”: balloons carrying copies of George Orwell’s  In the early nineteen-hundreds, the American writer O. Henry coined the term “banana republic” in a series of

In the early nineteen-hundreds, the American writer O. Henry coined the term “banana republic” in a series of