Giuliana Viglioni in Nature:

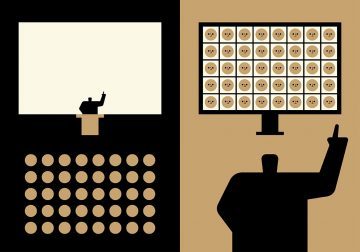

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, Adam Fortais had never attended a virtual conference. Now he’s sold on them — and doesn’t want to go back to conventional, in-person gatherings. That’s because of his experience of helping to instigate some virtual sessions for the March meeting of the American Physical Society (APS), after the organization cancelled the regular conference at short notice. “If given the option, I think I would almost always choose to do the virtual one,” says Fortais, a physicist at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario. “It just seems better to me in almost all ways.”

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, Adam Fortais had never attended a virtual conference. Now he’s sold on them — and doesn’t want to go back to conventional, in-person gatherings. That’s because of his experience of helping to instigate some virtual sessions for the March meeting of the American Physical Society (APS), after the organization cancelled the regular conference at short notice. “If given the option, I think I would almost always choose to do the virtual one,” says Fortais, a physicist at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario. “It just seems better to me in almost all ways.”

Fortais could get his wish. Since the coronavirus spread worldwide in early March, many scientific conferences scheduled for the first half of the year have migrated online, and organizers of meetings due to take place in the second half of 2020 are deciding whether they will go fully or partially virtual. Some researchers hope that the pandemic will finally push scientific societies to embrace a shift towards online conferences — a move that many scientists have long desired for environmental reasons and to allow broader participation. Scientists with disabilities and parents of young children are just two examples of the researchers who are benefiting from online meetings, says Kim Cobb, a climate scientist at the Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta. Cobb has been cutting back her own air travel since 2017, both to reduce her personal carbon footprint and to blaze a trail towards structural change in her discipline. She hopes the changes as a result of the pandemic will last long after it has ended. “In five years, we’ll be in a remarkably different place.”

More here.

There are some problems for which it’s very hard to find the answer, but very easy to check the answer if someone gives it to you. At least, we think there are such problems; whether or not they really exist is the famous

There are some problems for which it’s very hard to find the answer, but very easy to check the answer if someone gives it to you. At least, we think there are such problems; whether or not they really exist is the famous  One of the least expected aspects of 2020 has been the fact that epidemiological models have become both front-page news and a political football. Public health officials have consulted with epidemiological modelers for decades as they’ve attempted to handle diseases ranging from HIV to the seasonal flu. Before 2020, it had been rare for the role these models play to be recognized outside of this small circle of health policymakers.

One of the least expected aspects of 2020 has been the fact that epidemiological models have become both front-page news and a political football. Public health officials have consulted with epidemiological modelers for decades as they’ve attempted to handle diseases ranging from HIV to the seasonal flu. Before 2020, it had been rare for the role these models play to be recognized outside of this small circle of health policymakers. Published shortly after his death in 1633,

Published shortly after his death in 1633,  “I am unfortunately a complicated and difficult subject.” With these words of Martin Buber, Paul Mendes-Flohr lays down the challenge for his meticulous biography of the distinguished Jewish scholar, humanist, and author of I and Thou. “Complicated,” to be sure, and “difficult,” certainly; that goes with the territory of Buber’s at times maze-like philosophical explorations and heavily Germanic articulation. And one may add to these challenges the fact that—to quote this biographer—Buber was a “contested figure who evoked passionate, conflicting opinions about his person and his thought.” Yet these obstacles are by no means insurmountable, thanks to Mendes-Flohr’s philosophical acumen and gift for succinct expression. Indeed, in his capable hands Buber’s life makes for an engrossing, instructive tale, and an exemplary contribution to Yale’s “Jewish Lives Series.”

“I am unfortunately a complicated and difficult subject.” With these words of Martin Buber, Paul Mendes-Flohr lays down the challenge for his meticulous biography of the distinguished Jewish scholar, humanist, and author of I and Thou. “Complicated,” to be sure, and “difficult,” certainly; that goes with the territory of Buber’s at times maze-like philosophical explorations and heavily Germanic articulation. And one may add to these challenges the fact that—to quote this biographer—Buber was a “contested figure who evoked passionate, conflicting opinions about his person and his thought.” Yet these obstacles are by no means insurmountable, thanks to Mendes-Flohr’s philosophical acumen and gift for succinct expression. Indeed, in his capable hands Buber’s life makes for an engrossing, instructive tale, and an exemplary contribution to Yale’s “Jewish Lives Series.” As universities face major changes, their financial outlook is becoming dire. Revenues are plummeting as students (particularly international ones) remain home or rethink future plans, and endowment funds implode as stock markets drop.

As universities face major changes, their financial outlook is becoming dire. Revenues are plummeting as students (particularly international ones) remain home or rethink future plans, and endowment funds implode as stock markets drop. Writing from a Birmingham jail, Martin Luther King Jr famously told his anxious fellow clergymen that his non-violent protests would force those in power to negotiate for racial justice. “The time is always ripe to do right,” he wrote. On an early summer evening, two generations later,

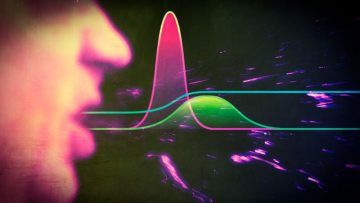

Writing from a Birmingham jail, Martin Luther King Jr famously told his anxious fellow clergymen that his non-violent protests would force those in power to negotiate for racial justice. “The time is always ripe to do right,” he wrote. On an early summer evening, two generations later,  Epidemiological studies are now revealing that the number of individuals who carry and can pass on the infection, yet remain completely asymptomatic, is larger than originally thought. Scientists believe these people have contributed to the spread of the virus in care homes, and they are central in the debate regarding face mask policies, as health officials attempt to avoid new waves of infections while societies reopen.

Epidemiological studies are now revealing that the number of individuals who carry and can pass on the infection, yet remain completely asymptomatic, is larger than originally thought. Scientists believe these people have contributed to the spread of the virus in care homes, and they are central in the debate regarding face mask policies, as health officials attempt to avoid new waves of infections while societies reopen. What’s your reaction when you see the term “double-entry book-keeping”? Do you associate it with cool, societal-changing innovations like the Internet, Google, social media, laptops, and smartphones? Probably not. Neither did I—until I was asked to write a brief article about the fifteenth century Italian mathematician Luca Pacioli, to go into the sale catalog for the upcoming (June) Christie’s auction of an original first edition of his famous book Summa de arithmetica, geometria, proportioni et proportionalita (“Summary of arithmetic, geometry, proportions and proportionality”), published in 1494, which I referred to in

What’s your reaction when you see the term “double-entry book-keeping”? Do you associate it with cool, societal-changing innovations like the Internet, Google, social media, laptops, and smartphones? Probably not. Neither did I—until I was asked to write a brief article about the fifteenth century Italian mathematician Luca Pacioli, to go into the sale catalog for the upcoming (June) Christie’s auction of an original first edition of his famous book Summa de arithmetica, geometria, proportioni et proportionalita (“Summary of arithmetic, geometry, proportions and proportionality”), published in 1494, which I referred to in  Each of us is different, in some way or another, from every other person. But some are more different than others — and the rest of the world never stops letting them know. Societies set up “norms” that define what constitute acceptable standards of behavior, appearance, and even belief. But there will always be those who find themselves, intentionally or not, in violation of those norms — people who we might label “weird.” Olga Khazan was weird in one particular way, growing up in a Russian immigrant family in the middle of Texas. Now as an established writer, she has been exploring what it means to be weird, and the senses in which that quality can both harm you and provide you with hidden advantages.

Each of us is different, in some way or another, from every other person. But some are more different than others — and the rest of the world never stops letting them know. Societies set up “norms” that define what constitute acceptable standards of behavior, appearance, and even belief. But there will always be those who find themselves, intentionally or not, in violation of those norms — people who we might label “weird.” Olga Khazan was weird in one particular way, growing up in a Russian immigrant family in the middle of Texas. Now as an established writer, she has been exploring what it means to be weird, and the senses in which that quality can both harm you and provide you with hidden advantages. Albert Memmi, the great Tunisian-born French Jewish intellectual,

Albert Memmi, the great Tunisian-born French Jewish intellectual,  The moralizing has begun.

The moralizing has begun.