Mathew Lawrence, Adrienne Buller, Joseph Baines & Sandy Hager over at Common Wealth:

Mathew Lawrence, Adrienne Buller, Joseph Baines & Sandy Hager over at Common Wealth:

A devastating public health crisis, Covid-19 has also triggered a profound crisis of the company: from vast multinational corporations to the small firms that are the lifeblood of local economies. The unprecedented economic fallout from the virus has exposed the inefficiencies and injustices embedded in the company’s operation – limitations that stretch back decades. Our response to this crisis cannot ignore these limitations when we emerge from the period of economic hibernation. Instead, it must reimagine the company so that it is democratic, resilient, and sustainable by design – and rebuild a new economy centred on meeting the needs of society and the environment.

Since the 1970s, the company has transformed from an institution focused on production – even if still one laced through with hierarchy and injustices – into an engine of increasing wealth extraction and growing financialisation, funnelling cash to shareholders and executive management in the form of dividends, share buybacks and share-based pay awards. This has been driven by key shifts in the legal, managerial, and ownership structures of the corporation, with an increasing share of corporate earnings redirected to investors and management over workers or re-investment. Shareholding has concentrated and corporate debt has soared, with UK listed company debt reaching record levels by 2018; mergers and acquisitions have created dominant oligopolies in key sectors; managerial power has grown; and labour has been subject to a relentless squeeze on wages, autonomy, and security in order to boost short-term profit.

More here.

Branko Milanovic over at his website, Global Inequality:

Branko Milanovic over at his website, Global Inequality: Erik D’Amato reviews Alex Cooley and Dan Nexon’s new book, Exit from Hegemony: The Unraveling of the American Global Order in The LA Review of Books:

Erik D’Amato reviews Alex Cooley and Dan Nexon’s new book, Exit from Hegemony: The Unraveling of the American Global Order in The LA Review of Books: John Quiggin in Aeon:

John Quiggin in Aeon:

On her first night in Los Angeles, the model-turned-author Susanna Moore slept in a broom cupboard. She was 21, and had been flown in by a producer to appear in the 1967 Dean Martin spy comedy, The Ambushers. Prior to this she had been working as a fashion model and was helping to put her husband, Bill, through college in Chicago. With barely a cent to her name, she arrived to find the hotel was not expecting her. The desk clerk took pity and sent her to the fourth floor where there was a tiny closet crammed with bleach, toilet brushes and mops. There Moore bedded down on a small rusty cot, the smell of ammonia in her nostrils. Despite this inauspicious start, she was “neither worried nor afraid”, and soon resolved to leave her husband and make LA her home.

On her first night in Los Angeles, the model-turned-author Susanna Moore slept in a broom cupboard. She was 21, and had been flown in by a producer to appear in the 1967 Dean Martin spy comedy, The Ambushers. Prior to this she had been working as a fashion model and was helping to put her husband, Bill, through college in Chicago. With barely a cent to her name, she arrived to find the hotel was not expecting her. The desk clerk took pity and sent her to the fourth floor where there was a tiny closet crammed with bleach, toilet brushes and mops. There Moore bedded down on a small rusty cot, the smell of ammonia in her nostrils. Despite this inauspicious start, she was “neither worried nor afraid”, and soon resolved to leave her husband and make LA her home. Metaphors of illness come in two varieties. We may give an illness a name that is not its own—“cancer is an invasion.” Or we may use the names of illnesses to talk about something else—“Stalinism is a cancer.” In the first case, Sontag says, “the disease itself becomes a metaphor”; in the second, the disease’s “horror is imposed on other things.” Sontag takes both to distort the patient’s experience of illness by overlaying it with meanings it does not deserve. But the two deserve separate treatments. “Stalinism is a cancer” exploits illness; it uses sickness to cast light on something else. It presupposes that cancer is more straightforward, more readily comprehensible than Stalinism—otherwise, why try to understand the latter in terms of the former? It obscures cancer precisely by presenting it as readily comprehensible. “Cancer is an invasion” is something else entirely, something far more likely to be used by someone seeking to make sense of their own sickness. Audre Lorde reaches for the image repeatedly in her memoir. “I am not only a casualty,” she writes in The Cancer Journals. “I have been to war, and still am. … I refuse to be reduced in my own eyes … from warrior to mere victim.”

Metaphors of illness come in two varieties. We may give an illness a name that is not its own—“cancer is an invasion.” Or we may use the names of illnesses to talk about something else—“Stalinism is a cancer.” In the first case, Sontag says, “the disease itself becomes a metaphor”; in the second, the disease’s “horror is imposed on other things.” Sontag takes both to distort the patient’s experience of illness by overlaying it with meanings it does not deserve. But the two deserve separate treatments. “Stalinism is a cancer” exploits illness; it uses sickness to cast light on something else. It presupposes that cancer is more straightforward, more readily comprehensible than Stalinism—otherwise, why try to understand the latter in terms of the former? It obscures cancer precisely by presenting it as readily comprehensible. “Cancer is an invasion” is something else entirely, something far more likely to be used by someone seeking to make sense of their own sickness. Audre Lorde reaches for the image repeatedly in her memoir. “I am not only a casualty,” she writes in The Cancer Journals. “I have been to war, and still am. … I refuse to be reduced in my own eyes … from warrior to mere victim.” Over the years, the horror of June 15, 1920, when three black men were lynched by a white mob in Duluth, faded away behind a “collective amnesia,” says author Michael Fedo. Faded away, at least, in the memories of Duluth’s white community. In the 1970s, when Fedo began researching what would become

Over the years, the horror of June 15, 1920, when three black men were lynched by a white mob in Duluth, faded away behind a “collective amnesia,” says author Michael Fedo. Faded away, at least, in the memories of Duluth’s white community. In the 1970s, when Fedo began researching what would become  In 1841, while aboard the whaler Acushnet, Herman Melville met William Chase among another ship’s complement. William lent Melville a book by his father, Owen Chase: “Narrative of the Most Extraordinary and Distressing Shipwreck of the Whale-Ship Essex.” Melville had read Jeremiah Reynolds’s violent account of a sperm whale “white as wool,” named — for his haunt near Mocha Island, off the coast of Chile — Mocha Dick. It’s unknown what led Melville to tweak Mocha to “Moby.” Good thing he did, and that Starbuck was the name he gave his first mate rather than his captain. Otherwise the novel would follow Starbuck’s obsession with a Mocha. Owen Chase gave Melville his climax: As Essex’s boats were harpooning female sperm whales, a huge male, around 85 feet, rushed and holed the 88-foot ship, twice. No whale had ever sunk a ship. “The reading of this wondrous story upon the landless sea, and so close to the very latitude of the shipwreck had a surprising effect upon me,” Melville later recalled.

In 1841, while aboard the whaler Acushnet, Herman Melville met William Chase among another ship’s complement. William lent Melville a book by his father, Owen Chase: “Narrative of the Most Extraordinary and Distressing Shipwreck of the Whale-Ship Essex.” Melville had read Jeremiah Reynolds’s violent account of a sperm whale “white as wool,” named — for his haunt near Mocha Island, off the coast of Chile — Mocha Dick. It’s unknown what led Melville to tweak Mocha to “Moby.” Good thing he did, and that Starbuck was the name he gave his first mate rather than his captain. Otherwise the novel would follow Starbuck’s obsession with a Mocha. Owen Chase gave Melville his climax: As Essex’s boats were harpooning female sperm whales, a huge male, around 85 feet, rushed and holed the 88-foot ship, twice. No whale had ever sunk a ship. “The reading of this wondrous story upon the landless sea, and so close to the very latitude of the shipwreck had a surprising effect upon me,” Melville later recalled. A grisly cultic murder is an unusual starting point for a work of philosophy, but this opening is typical of Justin E. H. Smith’s new book. It is one of many vivid impressionistic sketches – what Smith calls “instructive ornamentations” – employed to lend support to his dialectical thesis: that rationality is inextricably linked, in society as in the individual, to its irrational opposite. Rationality or reason (the terms are used interchangeably) never exists alone. It is always and everywhere mixed up with its ineliminable “dark side”, liable to erupt violently wherever faith in reason is strongest. Irrationality explores the manifestations of this enlightenment-into-darkness paradigm as it unfolds in history and contemporary politics.

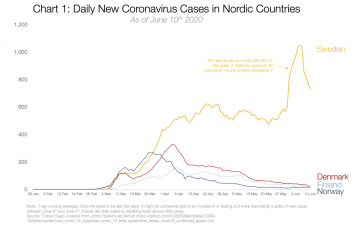

A grisly cultic murder is an unusual starting point for a work of philosophy, but this opening is typical of Justin E. H. Smith’s new book. It is one of many vivid impressionistic sketches – what Smith calls “instructive ornamentations” – employed to lend support to his dialectical thesis: that rationality is inextricably linked, in society as in the individual, to its irrational opposite. Rationality or reason (the terms are used interchangeably) never exists alone. It is always and everywhere mixed up with its ineliminable “dark side”, liable to erupt violently wherever faith in reason is strongest. Irrationality explores the manifestations of this enlightenment-into-darkness paradigm as it unfolds in history and contemporary politics. Sweden has famously followed a different coronavirus strategy than most of the rest of the Developed world: Let the virus run loose, curb it enough to make sure it doesn’t overwhelm the healthcare system like in Hubei, Italy or Spain, but don’t try to eliminate it. They think stopping it completely is impossible. The natural consequence is that most citizens get infected, and that eventually slows down the epidemic. That’s why, in short, people call that strategy “Herd Immunity”.

Sweden has famously followed a different coronavirus strategy than most of the rest of the Developed world: Let the virus run loose, curb it enough to make sure it doesn’t overwhelm the healthcare system like in Hubei, Italy or Spain, but don’t try to eliminate it. They think stopping it completely is impossible. The natural consequence is that most citizens get infected, and that eventually slows down the epidemic. That’s why, in short, people call that strategy “Herd Immunity”. Having “been reduced to the perplexity of realizing that he did not know… he will go on and discover,” Plato writes of the boy who “feels the difficulty he is in” after attempting to solve Socrates’ riddles. Socrates argues that “by causing him to doubt and giving him the torpedo’s shock” of his own ignorance, “he will push on in the search gladly, as lacking knowledge; whereas then he would have been only too ready to suppose he was right.” Encountering contradictions and complexity beyond his comprehension plunged the boy into aporia — an impasse, a quandary one cannot resolve, a state of puzzlement, a doubting and bewilderment, a being-at-a-loss. Aporia is the dazzling of the mind by the intricacy of existence. While this state seems empty, the paucity of knowledge in aporia is fertile. Specifically, aporia created by literature offers the following routes of learning: it fosters epistemic humility by revealing our uncertainty, broadens our possibilities by expanding our imaginative horizons, and promotes existential authenticity.

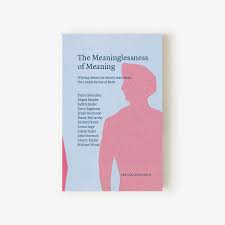

Having “been reduced to the perplexity of realizing that he did not know… he will go on and discover,” Plato writes of the boy who “feels the difficulty he is in” after attempting to solve Socrates’ riddles. Socrates argues that “by causing him to doubt and giving him the torpedo’s shock” of his own ignorance, “he will push on in the search gladly, as lacking knowledge; whereas then he would have been only too ready to suppose he was right.” Encountering contradictions and complexity beyond his comprehension plunged the boy into aporia — an impasse, a quandary one cannot resolve, a state of puzzlement, a doubting and bewilderment, a being-at-a-loss. Aporia is the dazzling of the mind by the intricacy of existence. While this state seems empty, the paucity of knowledge in aporia is fertile. Specifically, aporia created by literature offers the following routes of learning: it fosters epistemic humility by revealing our uncertainty, broadens our possibilities by expanding our imaginative horizons, and promotes existential authenticity. Pretentiously Opaque would perhaps have made a good alternative title for The Meaninglessness of Meaning, a slim volume collecting some of the LRB’s best writing on “the Theory Wars”, ranging from Brigid Brophy’s review of Colin MacCabe’s James Joyce and the Revolution of the Word (1979) to Adam Shatz’s essay-portrait of Claude Lévi-Strauss (2011), and touching, via essays on various gurus, on most of the key theoretical points in between: Pierre Bourdieu on Jean-Paul Sartre; Richard Rorty on Foucault; Michael Wood on Roland Barthes; Frank Kermode on Paul de Man; Judith Butler on Jacques Derrida; and Lorna Sage on Toril Moi, among others. Pretentious opacity is not, of course, the sort of thing you tend to find in the LRB – as Adam Shatz notes in an elegant introduction, “you’ll never see a piece of ‘pure’ theory in the LRB”, because the paper is committed to “the kind of lucid exposition of ideas that theorists have rejected in favour of a more Baroque, circuitous, self-consciously rarefied style”. The Meaninglessness of Meaning is therefore a partial (and inevitably lopsided) record of how theory fared once it ventured past the campus gates and found itself wandering the streets of the metropolis. More or less useless, I would imagine, to anyone who doesn’t already know something about theory, it nonetheless provokes some interesting reflections on the world that theory made – which is our world, whether we like it or not.

Pretentiously Opaque would perhaps have made a good alternative title for The Meaninglessness of Meaning, a slim volume collecting some of the LRB’s best writing on “the Theory Wars”, ranging from Brigid Brophy’s review of Colin MacCabe’s James Joyce and the Revolution of the Word (1979) to Adam Shatz’s essay-portrait of Claude Lévi-Strauss (2011), and touching, via essays on various gurus, on most of the key theoretical points in between: Pierre Bourdieu on Jean-Paul Sartre; Richard Rorty on Foucault; Michael Wood on Roland Barthes; Frank Kermode on Paul de Man; Judith Butler on Jacques Derrida; and Lorna Sage on Toril Moi, among others. Pretentious opacity is not, of course, the sort of thing you tend to find in the LRB – as Adam Shatz notes in an elegant introduction, “you’ll never see a piece of ‘pure’ theory in the LRB”, because the paper is committed to “the kind of lucid exposition of ideas that theorists have rejected in favour of a more Baroque, circuitous, self-consciously rarefied style”. The Meaninglessness of Meaning is therefore a partial (and inevitably lopsided) record of how theory fared once it ventured past the campus gates and found itself wandering the streets of the metropolis. More or less useless, I would imagine, to anyone who doesn’t already know something about theory, it nonetheless provokes some interesting reflections on the world that theory made – which is our world, whether we like it or not. W

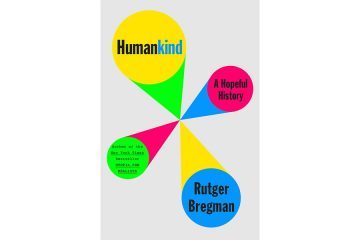

W During the coronavirus pandemic, millions of people are staying home in part to protect the most vulnerable members of their communities from COVID-19. When they do venture out, many don masks, which do less to protect them than to shield any strangers with whom they might inadvertently come into contact. Perhaps the time is ripe to consider the provocative thesis of Dutch historian Rutger Bregman’s new book, “Humankind: A Hopeful History.” His “radical idea”? That “most people, deep down, are pretty decent.” For far too long, Bregman argues, the opposite has been assumed to be true: “There is a persistent myth that by their very nature humans are selfish, aggressive and quick to panic.” Many of our institutions reflect the view of humanity articulated by 17th-century English philosopher Thomas Hobbes, who believed that without a strong ruler, human beings would revert to “a condition of war of all against all.” For his part, Bregman is more aligned with the work of Enlightenment thinker Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who regarded civilization itself as the corrupting force, introducing war, crime, and other horrors that didn’t exist when Homo sapiens lived in a “state of nature.”

During the coronavirus pandemic, millions of people are staying home in part to protect the most vulnerable members of their communities from COVID-19. When they do venture out, many don masks, which do less to protect them than to shield any strangers with whom they might inadvertently come into contact. Perhaps the time is ripe to consider the provocative thesis of Dutch historian Rutger Bregman’s new book, “Humankind: A Hopeful History.” His “radical idea”? That “most people, deep down, are pretty decent.” For far too long, Bregman argues, the opposite has been assumed to be true: “There is a persistent myth that by their very nature humans are selfish, aggressive and quick to panic.” Many of our institutions reflect the view of humanity articulated by 17th-century English philosopher Thomas Hobbes, who believed that without a strong ruler, human beings would revert to “a condition of war of all against all.” For his part, Bregman is more aligned with the work of Enlightenment thinker Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who regarded civilization itself as the corrupting force, introducing war, crime, and other horrors that didn’t exist when Homo sapiens lived in a “state of nature.” Roughly half of Earth’s ice-free land remains without significant human influence, according to a study from a team of international researchers led by the National Geographic Society and the University of California, Davis. The study, published in the journal Global Change Biology, compared four recent global maps of the conversion of natural lands to anthropogenic land uses to reach its conclusions. The more impacted half of Earth’s lands includes cities, croplands, and places intensively ranched or mined. “The encouraging takeaway from this study is that if we act quickly and decisively, there is a slim window in which we can still conserve roughly half of Earth’s land in a relatively intact state,” said lead author Jason Riggio, a postdoctoral scholar at the UC Davis Museum of Wildlife and Fish Biology.

Roughly half of Earth’s ice-free land remains without significant human influence, according to a study from a team of international researchers led by the National Geographic Society and the University of California, Davis. The study, published in the journal Global Change Biology, compared four recent global maps of the conversion of natural lands to anthropogenic land uses to reach its conclusions. The more impacted half of Earth’s lands includes cities, croplands, and places intensively ranched or mined. “The encouraging takeaway from this study is that if we act quickly and decisively, there is a slim window in which we can still conserve roughly half of Earth’s land in a relatively intact state,” said lead author Jason Riggio, a postdoctoral scholar at the UC Davis Museum of Wildlife and Fish Biology.