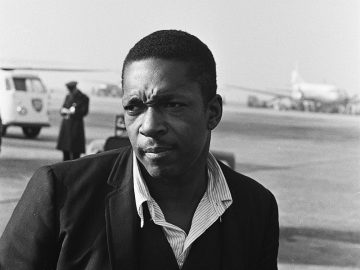

Ismael Muhammad in The Paris Review:

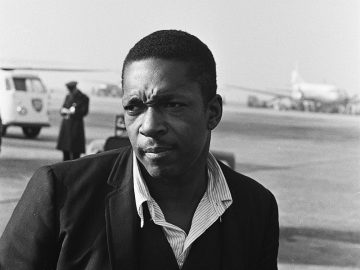

The John Coltrane Quartet’s “Alabama” is a strange song, incongruous with the rest of the album on which it appears. Inserted into Coltrane’s 1964 album Live at Birdland, it’s a studio track that confounds the virtuosic post-bop bliss of the album’s first three tracks, live recordings that include a jittery rendition of Mongo Santamaria’s “Afro Blue.” All of that collapses when we reach the sunken melancholy of “Alabama.” We are far, now, from the cascades of sound that Coltrane introduced us to in “Giant Steps,” far from the sonic innovations and precise phrasing he refined in this album’s live recordings. Here, Coltrane’s saxophone sounds hoarse and enfeebled, until it collapses on the threshold of a hole in the ground.

The John Coltrane Quartet’s “Alabama” is a strange song, incongruous with the rest of the album on which it appears. Inserted into Coltrane’s 1964 album Live at Birdland, it’s a studio track that confounds the virtuosic post-bop bliss of the album’s first three tracks, live recordings that include a jittery rendition of Mongo Santamaria’s “Afro Blue.” All of that collapses when we reach the sunken melancholy of “Alabama.” We are far, now, from the cascades of sound that Coltrane introduced us to in “Giant Steps,” far from the sonic innovations and precise phrasing he refined in this album’s live recordings. Here, Coltrane’s saxophone sounds hoarse and enfeebled, until it collapses on the threshold of a hole in the ground.

In “Alabama,” Coltrane asks us to bear witness to this hole in the ground, which is also a hole in America’s story, which is also a hole in the heart of black Americans. He wants us to grieve alongside him at this absence. The quartet recorded the track in November 1963, two months after the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, made an absence of four little black girls. When I listen to Coltrane playing over Tyner’s piano I hear smoke rising up from a smoldering crater, mingling with the voices of the dead. He asks us to peer down into the hole, to toss ourselves over into this absence. Just past the one-minute mark, even this funeral dirge collapses in on itself, as Coltrane’s saxophone sinks into a descending arpeggio, coaxing us in.

…I started listening to and thinking about “Alabama” a lot in the aftermath of Philando Castile’s murder in the summer of 2016, which was reminiscent of the murders of Samuel DuBose, Alton Sterling, Terence Crutcher, Walter Scott, Jamar Clark, Sandra Bland, and countless others. I’d lay down and loop the song through my bedroom speakers because the sonic landscape that Coltrane conjures on the track suggests something about the temporality in which black grief lives, the way that black people are forced to grieve our dead so often that the work of grieving never ends. You don’t even have time to grieve one new absence before the next one arrives. (We hadn’t time to grieve Ahmaud Arbery before we saw the video of Floyd’s murder.) “Alabama” gives this unceasing immersion in grief a form. It’s there in the song’s disconcerting stops and starts, its disarticulated notes, its willingness to abandon virtuosity in favor of a style of playing that is repetitive, diffuse, tentative, and dissonant.

More here.

Steven Levine has written a superb book. The title advertises three perennially puzzling topics: pragmatism, objectivity, and experience. Some background will help locate his project on a larger map.

Steven Levine has written a superb book. The title advertises three perennially puzzling topics: pragmatism, objectivity, and experience. Some background will help locate his project on a larger map.

A team of scientists hunting dark matter has recorded suspicious pings coming from a vat of liquid xenon underneath a mountain in Italy. They are not claiming to have discovered dark matter — or anything, for that matter — yet. But these pings, they say, could be tapping out a new view of the universe.

A team of scientists hunting dark matter has recorded suspicious pings coming from a vat of liquid xenon underneath a mountain in Italy. They are not claiming to have discovered dark matter — or anything, for that matter — yet. But these pings, they say, could be tapping out a new view of the universe. Nussbaum concludes that the cosmopolitan tradition “must be revised but need not be rejected.” She proposes that it be replaced by her own version of the “Capability Approach” to development. Conceived by the Nobel laureate economist Amartya Sen as an alternative to the prevailing mode of Western-exported market fundamentalism, the Capability Approach challenges the central tenets of economic globalization in its modern context: free trade, floating exchange rates, capital account and labor market “liberalization,” and so forth. In lieu of a sole focus on GDP and strictly monetary metrics of growth, the Capability Approach advocates a concern with the positive freedoms and opportunities that follow from investments in education, health care, leisure, environmental sustainability, and other factors.

Nussbaum concludes that the cosmopolitan tradition “must be revised but need not be rejected.” She proposes that it be replaced by her own version of the “Capability Approach” to development. Conceived by the Nobel laureate economist Amartya Sen as an alternative to the prevailing mode of Western-exported market fundamentalism, the Capability Approach challenges the central tenets of economic globalization in its modern context: free trade, floating exchange rates, capital account and labor market “liberalization,” and so forth. In lieu of a sole focus on GDP and strictly monetary metrics of growth, the Capability Approach advocates a concern with the positive freedoms and opportunities that follow from investments in education, health care, leisure, environmental sustainability, and other factors. Collective demonizations of prominent cultural figures were an integral part of the Soviet culture of denunciation that pervaded every workplace and apartment building. Perhaps the most famous such episode began on Oct. 23, 1958, when the Nobel committee informed Soviet writer Boris Pasternak that he had been selected for the Nobel Prize in literature—and plunged the writer’s life into hell. Ever since Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago had been first published the previous year (in Italy, since the writer could not publish it at home) the Communist Party and the Soviet literary establishment had their knives out for him. To the establishment, the Nobel Prize added insult to grave injury.

Collective demonizations of prominent cultural figures were an integral part of the Soviet culture of denunciation that pervaded every workplace and apartment building. Perhaps the most famous such episode began on Oct. 23, 1958, when the Nobel committee informed Soviet writer Boris Pasternak that he had been selected for the Nobel Prize in literature—and plunged the writer’s life into hell. Ever since Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago had been first published the previous year (in Italy, since the writer could not publish it at home) the Communist Party and the Soviet literary establishment had their knives out for him. To the establishment, the Nobel Prize added insult to grave injury. A well-worn science-fiction trope imagines space travelers going into suspended animation as they head into deep space. Closer to reality are actual efforts to slow biological processes to a fraction of their normal rate by replacing blood with ice-cold saline to prevent cell death in severe trauma. But saline transfusions or other exotic measures are not ideal for ratcheting down a body’s metabolism because they risk damaging tissue.

A well-worn science-fiction trope imagines space travelers going into suspended animation as they head into deep space. Closer to reality are actual efforts to slow biological processes to a fraction of their normal rate by replacing blood with ice-cold saline to prevent cell death in severe trauma. But saline transfusions or other exotic measures are not ideal for ratcheting down a body’s metabolism because they risk damaging tissue. The John Coltrane Quartet’s “Alabama” is a strange song, incongruous with the rest of the album on which it appears. Inserted into Coltrane’s 1964 album Live at Birdland, it’s a studio track that confounds the virtuosic post-bop bliss of the album’s first three tracks, live recordings that include a jittery rendition of Mongo Santamaria’s “Afro Blue.” All of that collapses when we reach the sunken melancholy of “Alabama.” We are far, now, from the cascades of sound that Coltrane introduced us to in “Giant Steps,” far from the sonic innovations and precise phrasing he refined in this album’s live recordings. Here, Coltrane’s saxophone sounds hoarse and enfeebled, until it collapses on the threshold of a hole in the ground.

The John Coltrane Quartet’s “Alabama” is a strange song, incongruous with the rest of the album on which it appears. Inserted into Coltrane’s 1964 album Live at Birdland, it’s a studio track that confounds the virtuosic post-bop bliss of the album’s first three tracks, live recordings that include a jittery rendition of Mongo Santamaria’s “Afro Blue.” All of that collapses when we reach the sunken melancholy of “Alabama.” We are far, now, from the cascades of sound that Coltrane introduced us to in “Giant Steps,” far from the sonic innovations and precise phrasing he refined in this album’s live recordings. Here, Coltrane’s saxophone sounds hoarse and enfeebled, until it collapses on the threshold of a hole in the ground. Last summer, Nikil Saval was best known as a head editor for the literary and political magazine n+1. He wrote freelance articles about architecture and design for The New York Times and The New Yorker. He used a Motorola razr flip phone.

Last summer, Nikil Saval was best known as a head editor for the literary and political magazine n+1. He wrote freelance articles about architecture and design for The New York Times and The New Yorker. He used a Motorola razr flip phone. The World According to Physics, by the British physicist Jim Al-Khalili, looks less like a

The World According to Physics, by the British physicist Jim Al-Khalili, looks less like a  Even the way in which coronavirus data is presented can radically change our perception of its impact, depending on which factors have been included and which have been discarded.

Even the way in which coronavirus data is presented can radically change our perception of its impact, depending on which factors have been included and which have been discarded. They have always been with me, these two fears: of boredom and bad smells. I have no memory of a life free of them.

They have always been with me, these two fears: of boredom and bad smells. I have no memory of a life free of them. The literary models Machado mentions in his preface are Laurence Sterne, Xavier de Maistre, and Almeida Garrett, but behind the title there may also be an ironic reference to Chateaubriand’s Mémoires d’outre-tombe (Memoirs from Beyond the Grave), published posthumously in 1849 and 1850. Those memoirs filled two volumes; their author was a diplomat, politician, writer, historian, and supposed founder of French Romanticism. Brás Cubas’s posthumous memoirs (which are written from beyond the grave) fill a scant two hundred pages and the narrator is, by his own blithe admission, a complete mediocrity whose life can be summed up by a series of negatives. Echoes of Sterne, Maistre, and Garrett are definitely all there in the brief chapters, the oblique chapter titles, the non sequiturs, and the half-baked philosophy, and yet in many ways the book is also a straightforward nineteenth-century realist novel, with its jabs at the hypocrisy of middle-class society, and the standard themes of adultery, money, marriage, miserliness, and profligacy. Machado manages, seamlessly, to combine realism and the fantastic, and the novel’s fragmentary, allusive style and its frequent inclusion of us, the readers, strikes us now as very modern, as does Brás Cubas’s insistence, more than once, that this is not a novel at all.

The literary models Machado mentions in his preface are Laurence Sterne, Xavier de Maistre, and Almeida Garrett, but behind the title there may also be an ironic reference to Chateaubriand’s Mémoires d’outre-tombe (Memoirs from Beyond the Grave), published posthumously in 1849 and 1850. Those memoirs filled two volumes; their author was a diplomat, politician, writer, historian, and supposed founder of French Romanticism. Brás Cubas’s posthumous memoirs (which are written from beyond the grave) fill a scant two hundred pages and the narrator is, by his own blithe admission, a complete mediocrity whose life can be summed up by a series of negatives. Echoes of Sterne, Maistre, and Garrett are definitely all there in the brief chapters, the oblique chapter titles, the non sequiturs, and the half-baked philosophy, and yet in many ways the book is also a straightforward nineteenth-century realist novel, with its jabs at the hypocrisy of middle-class society, and the standard themes of adultery, money, marriage, miserliness, and profligacy. Machado manages, seamlessly, to combine realism and the fantastic, and the novel’s fragmentary, allusive style and its frequent inclusion of us, the readers, strikes us now as very modern, as does Brás Cubas’s insistence, more than once, that this is not a novel at all.

The new season of my

The new season of my  Yesterday I went food shopping in the now quasi-military operation of a big grocery store near Boston. Near the entrance, I stopped to take a picture of an advertising placard—one of the neighboring stores touting its “Spring 2020 bridal collection.” It’s harder than usual to begrudge people their attempts to make money right now. We’ve learned how fragile the world’s systems of income are, even for those who make far more than they need. Airlines’ business can evaporate from one week to the next. Hotels can empty overnight. Who knew it could happen everywhere across the world at once? So there was pathos in the timing of the ad, which was very likely to fail. But the reason I stopped to take a picture, and the reason the picture has become a symbol of the moment for me: it featured an airbrushed photograph of a tall, white, easygoing, never-in-her-life-hungry bride—and passing behind her, from my frame of reference though of course not the bride’s, was a woman in blue nitrile gloves and a face mask, pushing a shopping cart back toward her isolation.

Yesterday I went food shopping in the now quasi-military operation of a big grocery store near Boston. Near the entrance, I stopped to take a picture of an advertising placard—one of the neighboring stores touting its “Spring 2020 bridal collection.” It’s harder than usual to begrudge people their attempts to make money right now. We’ve learned how fragile the world’s systems of income are, even for those who make far more than they need. Airlines’ business can evaporate from one week to the next. Hotels can empty overnight. Who knew it could happen everywhere across the world at once? So there was pathos in the timing of the ad, which was very likely to fail. But the reason I stopped to take a picture, and the reason the picture has become a symbol of the moment for me: it featured an airbrushed photograph of a tall, white, easygoing, never-in-her-life-hungry bride—and passing behind her, from my frame of reference though of course not the bride’s, was a woman in blue nitrile gloves and a face mask, pushing a shopping cart back toward her isolation. The phenomenon that some people in Brookings, Oregon, would later call a miracle began in early July 2019, when the same monarch butterfly appeared in Holly Beyer’s yard almost every day for two weeks. Beyer recognized it by a scratch on one wing. She and a friend named it Ovaltine, inspired by ovum, for the way it encrusted the milkweed in Beyer’s garden with eggs. Each off-white bump was no larger than the tip of a sharpened pencil. Clustered together on the green leaves, they looked like blemishes, as if the milkweed had sprouted a case of adolescent acne.

The phenomenon that some people in Brookings, Oregon, would later call a miracle began in early July 2019, when the same monarch butterfly appeared in Holly Beyer’s yard almost every day for two weeks. Beyer recognized it by a scratch on one wing. She and a friend named it Ovaltine, inspired by ovum, for the way it encrusted the milkweed in Beyer’s garden with eggs. Each off-white bump was no larger than the tip of a sharpened pencil. Clustered together on the green leaves, they looked like blemishes, as if the milkweed had sprouted a case of adolescent acne.