Amit Chaudhuri at the TLS:

The Upanishads, then, can hardly be called originary. They sound more like the latest in a series of disagreements; a great deal has preceded them, and reached a state of ossification before their arrival. Among what they challenge is a particular sense of causality regarding the relationship between creation and creator, which seems to have been extant when they were composed. Many traditions believe in a first cause, after which the universe comes into existence and before which there was nothing. The Upanishad’s conception of consciousness – “He moves, and he moves not”; “He is far, and he is near” – complicates the point of origin. Again, unlike Descartes’s belief that thought is both a product and a proof of existence, the Upanishad’s “What cannot be thought with the mind, but that whereby the mind can think” introduces an absence at the heart of thought. If thought can’t conceive whatever it is that produces it, then thought can’t be wholly present – a formulation that’s antithetical to the Cartesian proclamation. And since causality constantly reasserts itself as a default mode of thinking throughout history, the Upanishads remain, essentially, oppositional. They can’t occupy the space of established thought, being opposed to that space. Nor can one reduce either the Upanishads or the Gita in sociological terms to being “Brahminical” without losing sight of the fact that their language is critical-poetic – that is, they raise a critique through paradox and metaphor – rather than dogmatic or hieratic.

The Upanishads, then, can hardly be called originary. They sound more like the latest in a series of disagreements; a great deal has preceded them, and reached a state of ossification before their arrival. Among what they challenge is a particular sense of causality regarding the relationship between creation and creator, which seems to have been extant when they were composed. Many traditions believe in a first cause, after which the universe comes into existence and before which there was nothing. The Upanishad’s conception of consciousness – “He moves, and he moves not”; “He is far, and he is near” – complicates the point of origin. Again, unlike Descartes’s belief that thought is both a product and a proof of existence, the Upanishad’s “What cannot be thought with the mind, but that whereby the mind can think” introduces an absence at the heart of thought. If thought can’t conceive whatever it is that produces it, then thought can’t be wholly present – a formulation that’s antithetical to the Cartesian proclamation. And since causality constantly reasserts itself as a default mode of thinking throughout history, the Upanishads remain, essentially, oppositional. They can’t occupy the space of established thought, being opposed to that space. Nor can one reduce either the Upanishads or the Gita in sociological terms to being “Brahminical” without losing sight of the fact that their language is critical-poetic – that is, they raise a critique through paradox and metaphor – rather than dogmatic or hieratic.

more here.

The secondary characters are extraordinary. As Penn State media professor Kevin Hagopian puts it in his film notes for the New York State Writers Institute, Odd Man Out is “festooned with gargoyles.” The crazed painter Lukey (Robert Newton) sees in Johnny’s suffering face the perfect model for a masterpiece of portraiture. With the bearing of a genteel bordello mistress, treacherous Theresa O’Brien (Maureen Delany) lets two of the bandits drink her whiskey in one room, while in another she informs the police of their whereabouts. Dim-witted Shell (F. J. McCormick), who collects birds and speaks in avian metaphors, discovers Johnny in a rubbish heap and relishes the reward he will get for turning in this bird with the wounded left wing. But Father Tom (W. G. Fay) persuades Shell that there is a greater reward than money and it is called Faith. When Shell wonders what Faith is, his roommate, a medical student, says, “It’s life.”

The secondary characters are extraordinary. As Penn State media professor Kevin Hagopian puts it in his film notes for the New York State Writers Institute, Odd Man Out is “festooned with gargoyles.” The crazed painter Lukey (Robert Newton) sees in Johnny’s suffering face the perfect model for a masterpiece of portraiture. With the bearing of a genteel bordello mistress, treacherous Theresa O’Brien (Maureen Delany) lets two of the bandits drink her whiskey in one room, while in another she informs the police of their whereabouts. Dim-witted Shell (F. J. McCormick), who collects birds and speaks in avian metaphors, discovers Johnny in a rubbish heap and relishes the reward he will get for turning in this bird with the wounded left wing. But Father Tom (W. G. Fay) persuades Shell that there is a greater reward than money and it is called Faith. When Shell wonders what Faith is, his roommate, a medical student, says, “It’s life.” A “

A “ Imagine: You pop a pill into your mouth and swallow it. It dissolves, releasing tiny particles that are absorbed and cause only cancerous cells to secrete a specific protein into your bloodstream. Two days from now, a finger-prick blood sample will expose whether you’ve got cancer and even give a rough idea of its extent. That’s a highly futuristic concept. But its realization may be only years, not decades, away.

Imagine: You pop a pill into your mouth and swallow it. It dissolves, releasing tiny particles that are absorbed and cause only cancerous cells to secrete a specific protein into your bloodstream. Two days from now, a finger-prick blood sample will expose whether you’ve got cancer and even give a rough idea of its extent. That’s a highly futuristic concept. But its realization may be only years, not decades, away.  Morgan Meis: Reading your second volume, I got a feeling that sometimes you struggled – as I think everyone has struggled – with where to place Calder in art history. Do you feel you reached a conclusion on that?

Morgan Meis: Reading your second volume, I got a feeling that sometimes you struggled – as I think everyone has struggled – with where to place Calder in art history. Do you feel you reached a conclusion on that? By now they are used to sharing their knowledge with journalists, but they’re less accustomed to talking about themselves. Many of them told me that they feel duty-bound and grateful to be helping their country at a time when so many others are ill or unemployed. But they’re also very tired, and dispirited by America’s continued inability to control a virus that many other nations have brought to heel.

By now they are used to sharing their knowledge with journalists, but they’re less accustomed to talking about themselves. Many of them told me that they feel duty-bound and grateful to be helping their country at a time when so many others are ill or unemployed. But they’re also very tired, and dispirited by America’s continued inability to control a virus that many other nations have brought to heel.  They had been public servants their whole careers. But when Hillary Clinton lost the 2016 election, two departing Obama officials were anxious for work. Trump’s win had caught them by surprise.

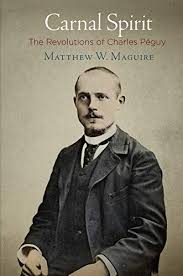

They had been public servants their whole careers. But when Hillary Clinton lost the 2016 election, two departing Obama officials were anxious for work. Trump’s win had caught them by surprise. To be sure, enlightened progressives were committed to science, positivism, and liberal democratic values—all of which the reactionaries rejected in favor of hierarchy and a highly traditionalist, and exclusively Catholic nationalism. It would seem to be a clear-cut struggle between the modernists and the antimodernists, but not as as Péguy saw it. He found the progressive faith in a scientifically driven and ever-improving future no more immanentizing, and no more modernist in its deepest aspirations, than the reactionaries’ vision. “These wrathful particularists,” Maguire explains, “often intimate a loyalty to older notions of transcendence—including religious faith and its avowal of abiding truths—but they conceive of that which transcends time only as an arrested immanence. They often present an amalgamated past as a unity…which now must be reinserted mechanically into the present, without creativity or surprise.” More ironically, some of the faux antimodernists (including the right-wing Action Française founder Charles Maurras, an admirer of the positivist Auguste Comte) also believed that “‘science’ would “confirm their particularism and prejudices.” Péguy’s critical stance toward both broad coalitions made him neither a modernist nor an antimodernist, Maguire argues, but something quite distinctive and instructive: an amodernist.

To be sure, enlightened progressives were committed to science, positivism, and liberal democratic values—all of which the reactionaries rejected in favor of hierarchy and a highly traditionalist, and exclusively Catholic nationalism. It would seem to be a clear-cut struggle between the modernists and the antimodernists, but not as as Péguy saw it. He found the progressive faith in a scientifically driven and ever-improving future no more immanentizing, and no more modernist in its deepest aspirations, than the reactionaries’ vision. “These wrathful particularists,” Maguire explains, “often intimate a loyalty to older notions of transcendence—including religious faith and its avowal of abiding truths—but they conceive of that which transcends time only as an arrested immanence. They often present an amalgamated past as a unity…which now must be reinserted mechanically into the present, without creativity or surprise.” More ironically, some of the faux antimodernists (including the right-wing Action Française founder Charles Maurras, an admirer of the positivist Auguste Comte) also believed that “‘science’ would “confirm their particularism and prejudices.” Péguy’s critical stance toward both broad coalitions made him neither a modernist nor an antimodernist, Maguire argues, but something quite distinctive and instructive: an amodernist. “I see no reason not to consider the Brontë cult a religion,” writes Judith Shulevitz. She calls the thousands of books inspired by the Brontës midrash, “the spinning of gloriously weird backstories or fairy tales prompted by gaps or contradictions in the narrative.”

“I see no reason not to consider the Brontë cult a religion,” writes Judith Shulevitz. She calls the thousands of books inspired by the Brontës midrash, “the spinning of gloriously weird backstories or fairy tales prompted by gaps or contradictions in the narrative.” When Howard Wolinsky was diagnosed with

When Howard Wolinsky was diagnosed with  In her 2019 book, “

In her 2019 book, “ A man finds himself in Antwerp with nothing to do. Then he remembers, among other things, that this is the town where the painter Peter Paul Rubens made his home. At first, this annoys him, because he has no interest whatsoever in the painter. But then he thinks, why not write a book about Rubens.

A man finds himself in Antwerp with nothing to do. Then he remembers, among other things, that this is the town where the painter Peter Paul Rubens made his home. At first, this annoys him, because he has no interest whatsoever in the painter. But then he thinks, why not write a book about Rubens. Creativity is one of those things that we all admire but struggle to define or make concrete. Music provides a useful laboratory in which to examine what creativity is all about — how do people become creative, what is happening in their brains during the creative process, and what kinds of creativity does the audience actually enjoy? David Rosen and Scott Miles are both neuroscientists and musicians who have been investigating this question from the perspective of both listeners and performers. They have been performing neuroscientific experiments to understand how the brain becomes creative, and founded Secret Chord Laboratories to develop software that will predict what kinds of music people will like.

Creativity is one of those things that we all admire but struggle to define or make concrete. Music provides a useful laboratory in which to examine what creativity is all about — how do people become creative, what is happening in their brains during the creative process, and what kinds of creativity does the audience actually enjoy? David Rosen and Scott Miles are both neuroscientists and musicians who have been investigating this question from the perspective of both listeners and performers. They have been performing neuroscientific experiments to understand how the brain becomes creative, and founded Secret Chord Laboratories to develop software that will predict what kinds of music people will like.