Göran Therborn in The Conversation:

Göran Therborn in The Conversation:

The possibilities of flourishing as a human are shaped by processes of (in)equality. Differences are either given – by God or by Nature – or chosen as lifestyles.

Unlike difference, inequality is a historical social construction.

The three-dimensionality of humanity gives us three kinds of human inequality. These are vital, existential and resource.

The three kinds of human inequality

Vital inequality refers to socially determined distributions of health and ill health and of your lifespan. It can be measured in life expectancy and in health expectancy or your years without serious illness. Where demographic life tables are missing, infant and child mortality are more accessible indicators.

Existential inequality sums up the unequal social treatment of persons. On one end of the spectrum resides denial of recognition, autonomy, existential security, dignity and respect. These can be achieved through acts of neglect, bullying, degradation and humiliation. The ultimate result is a denial of their humanness. At the opposite end are selective attention, freedom, emotional security, encouragement, respect and admiration.

Existential inequality is structured and processed by categories and lenses of othering – such as sex, race, ethnicity, caste or religion. It is arguably the most hurtful and wounding of inequalities.

More here.

Sophie Gilbert in The Atlantic:

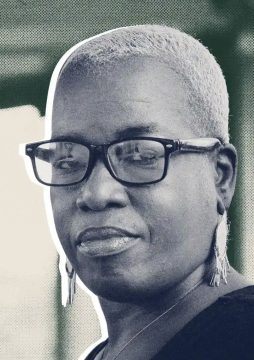

Sophie Gilbert in The Atlantic: The 19th Amendment, ratified in August 1920, paved the way for American women to vote, but the educator and activist Mary McLeod Bethune knew the work had only just begun: The amendment alone would not guarantee political power to black women. Thanks to Bethune’s work that year to register and mobilize black voters in her hometown of Daytona, Florida, new black voters soon outnumbered new white voters in the city. But a reign of terror followed. That fall, the Ku Klux Klan marched on Bethune’s boarding school for black girls; two years later, ahead of the 1922 elections, the Klan paid another threatening visit, as over 100 robed figures carrying banners emblazoned with the words “white supremacy” marched on the school in retaliation against Bethune’s continued efforts to get black women to the polls. Informed of the incoming nightriders, Bethune took charge: “Get the students into the dormitory,” she told the teachers, “get them into bed, do not share what is happening right now.” The students safely tucked in, Bethune directed her faculty: “The Ku Klux Klan is marching on our campus, and they intend to burn some buildings.”

The 19th Amendment, ratified in August 1920, paved the way for American women to vote, but the educator and activist Mary McLeod Bethune knew the work had only just begun: The amendment alone would not guarantee political power to black women. Thanks to Bethune’s work that year to register and mobilize black voters in her hometown of Daytona, Florida, new black voters soon outnumbered new white voters in the city. But a reign of terror followed. That fall, the Ku Klux Klan marched on Bethune’s boarding school for black girls; two years later, ahead of the 1922 elections, the Klan paid another threatening visit, as over 100 robed figures carrying banners emblazoned with the words “white supremacy” marched on the school in retaliation against Bethune’s continued efforts to get black women to the polls. Informed of the incoming nightriders, Bethune took charge: “Get the students into the dormitory,” she told the teachers, “get them into bed, do not share what is happening right now.” The students safely tucked in, Bethune directed her faculty: “The Ku Klux Klan is marching on our campus, and they intend to burn some buildings.” More research emerged this week in potential support of using the tuberculosis vaccine Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (

More research emerged this week in potential support of using the tuberculosis vaccine Bacillus Calmette-Guerin ( Identity politics has become a secular religion and, like any strict sect, apostates are severely punished.

Identity politics has become a secular religion and, like any strict sect, apostates are severely punished. Here’s a deceptively simple exercise: Come up with a random phone number. Seven digits in a sequence, chosen so that every digit is equally likely, and so that your choice of one digit doesn’t affect the next. Odds are, you can’t. (But don’t take my word for it:

Here’s a deceptively simple exercise: Come up with a random phone number. Seven digits in a sequence, chosen so that every digit is equally likely, and so that your choice of one digit doesn’t affect the next. Odds are, you can’t. (But don’t take my word for it:  Sadly, you know that your side is losing the war of ideas when they start handing propaganda victories to the side you despise on a platter. Three years ago, in the context of a Lee statue that was going to be taken down, after that terrible anti-Semitic Charlottesville rally by white supremacists, Trump made a loathsome remark about there being “fine people” on all sides and also asked a journalist that if it was Lee today, would it be Jefferson or Washington next? I of course dismissed Trump’s remark as racist and ignorant; he would not be able to recite the Declaration of Independence if it came wafting down at him in a MAGA hat. But now I am horrified that liberals are providing him with ample ammunition by validating his words. A protest in San Francisco toppled a statue of Ulysses S. Grant – literally the man who defeated the Confederacy and destroyed the first KKK – and

Sadly, you know that your side is losing the war of ideas when they start handing propaganda victories to the side you despise on a platter. Three years ago, in the context of a Lee statue that was going to be taken down, after that terrible anti-Semitic Charlottesville rally by white supremacists, Trump made a loathsome remark about there being “fine people” on all sides and also asked a journalist that if it was Lee today, would it be Jefferson or Washington next? I of course dismissed Trump’s remark as racist and ignorant; he would not be able to recite the Declaration of Independence if it came wafting down at him in a MAGA hat. But now I am horrified that liberals are providing him with ample ammunition by validating his words. A protest in San Francisco toppled a statue of Ulysses S. Grant – literally the man who defeated the Confederacy and destroyed the first KKK – and  Barbara Ehrenreich was born in Butte, Montana, where her family had lived for generations, in 1941. Most of her male ancestors lost fingers working in nearby copper mines. But her father attended night school, then won a scholarship to Carnegie Mellon; the family moved to Pittsburgh and rose into the middle class. Ehrenreich studied physics in college, got a doctorate in cell biology, and, in the late sixties, alongside her husband at the time, John Ehrenreich, she became involved in health-care organizing and antiwar activism.

Barbara Ehrenreich was born in Butte, Montana, where her family had lived for generations, in 1941. Most of her male ancestors lost fingers working in nearby copper mines. But her father attended night school, then won a scholarship to Carnegie Mellon; the family moved to Pittsburgh and rose into the middle class. Ehrenreich studied physics in college, got a doctorate in cell biology, and, in the late sixties, alongside her husband at the time, John Ehrenreich, she became involved in health-care organizing and antiwar activism. Initially, the street was named after a British doctor/spy named James Burnes. Although the name was changed to Muhammad Bin Qasim Road Post-Partition, it is still known as Burns Road or more affectionately, “Buns Road”. But the neighborhoods around Burns Road are considered to have housed the earliest settlements in the city of Karachi, dating back to 1857.

Initially, the street was named after a British doctor/spy named James Burnes. Although the name was changed to Muhammad Bin Qasim Road Post-Partition, it is still known as Burns Road or more affectionately, “Buns Road”. But the neighborhoods around Burns Road are considered to have housed the earliest settlements in the city of Karachi, dating back to 1857. Biography drags after Szapocznikow like a phantom limb, threatening to eclipse a practice as rooted in materiality and experiment as it is in the individual life experience of a body and mind. Born to a Jewish family in Kalisz, Poland, in 1926, she survived two ghettos and three concentration camps, as well as tuberculosis, before dying of breast cancer at age forty-six. Her work has frequently suffered from being interpreted too literally, theorized as representations of trauma or of psychic wounds. But every encounter I’ve had demands the opposite: The abstracted figuration Szapocznikow pursued in this later work, which hovers between the real body and its imagined or felt states, demands nuanced reading. We have the body truncated, unheroic, beguiling, as in her colored polyester resin lamps, mouths, and breasts lit from within—glowing sentinels pink, flesh colored, black, crimson. The body that grows where it shouldn’t, whose parts we cannot integrate, appears unnatural but unsettlingly erotic, tactile, as in two works titled Tumeur (Tumor), both made around 1970, consisting of lumpy mounds of resin and gauze, with ruby-red lips straining to the surface from within.

Biography drags after Szapocznikow like a phantom limb, threatening to eclipse a practice as rooted in materiality and experiment as it is in the individual life experience of a body and mind. Born to a Jewish family in Kalisz, Poland, in 1926, she survived two ghettos and three concentration camps, as well as tuberculosis, before dying of breast cancer at age forty-six. Her work has frequently suffered from being interpreted too literally, theorized as representations of trauma or of psychic wounds. But every encounter I’ve had demands the opposite: The abstracted figuration Szapocznikow pursued in this later work, which hovers between the real body and its imagined or felt states, demands nuanced reading. We have the body truncated, unheroic, beguiling, as in her colored polyester resin lamps, mouths, and breasts lit from within—glowing sentinels pink, flesh colored, black, crimson. The body that grows where it shouldn’t, whose parts we cannot integrate, appears unnatural but unsettlingly erotic, tactile, as in two works titled Tumeur (Tumor), both made around 1970, consisting of lumpy mounds of resin and gauze, with ruby-red lips straining to the surface from within. They blew up the mausoleum—or tried to—during a live broadcast on Bulgarian national television on August 21, 1999. It was a hot and cloudless day in the capital city of Sofia, perfect weather for a demolition. Ten years after the collapse of the country’s Communist regime there was still unfinished business to take care of. The mausoleum’s one and only occupant, the mummy of Georgi Dimitrov, “the Great Leader and Teacher of the Bulgarian People,” had already been removed from its glass sarcophagus, then cremated and buried at Sofia’s Central Cemetery. Now the tomb had to go.

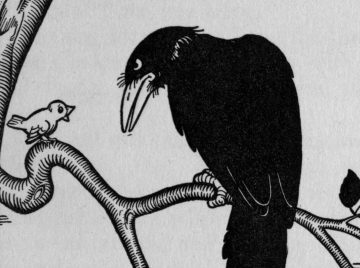

They blew up the mausoleum—or tried to—during a live broadcast on Bulgarian national television on August 21, 1999. It was a hot and cloudless day in the capital city of Sofia, perfect weather for a demolition. Ten years after the collapse of the country’s Communist regime there was still unfinished business to take care of. The mausoleum’s one and only occupant, the mummy of Georgi Dimitrov, “the Great Leader and Teacher of the Bulgarian People,” had already been removed from its glass sarcophagus, then cremated and buried at Sofia’s Central Cemetery. Now the tomb had to go. Bird omens once warned the ancients of the future. In Greece and Rome, for example, avian augury involved seers trained in the art of reading the flight of birds, who sought to make sense of a chaotic world through decoding messages from the gods. Since bird omens—or “auspices,” Latin for this kind of divination—often warned of disaster, ignoring or misreading them could be catastrophic. Ancient audiences watched tragedy unfold when hubristic rulers disregarded their augurs’ reading of these omens. (The two eagles that violently destroy a pregnant hare at the beginning of Aeschylus’s play Agamemnon, for example, forecast a Greek victory but prompt Agamemnon’s sacrifice of his daughter Iphigenia, leading, in turn, to his murder at the hands of his wife, Clytemnestra.) The legacy of bird divination is etymologically evident in such words as augury, inauguration, and auspicious (from the Latin augur and auspex). Birds, it seems, continue to point to the future.

Bird omens once warned the ancients of the future. In Greece and Rome, for example, avian augury involved seers trained in the art of reading the flight of birds, who sought to make sense of a chaotic world through decoding messages from the gods. Since bird omens—or “auspices,” Latin for this kind of divination—often warned of disaster, ignoring or misreading them could be catastrophic. Ancient audiences watched tragedy unfold when hubristic rulers disregarded their augurs’ reading of these omens. (The two eagles that violently destroy a pregnant hare at the beginning of Aeschylus’s play Agamemnon, for example, forecast a Greek victory but prompt Agamemnon’s sacrifice of his daughter Iphigenia, leading, in turn, to his murder at the hands of his wife, Clytemnestra.) The legacy of bird divination is etymologically evident in such words as augury, inauguration, and auspicious (from the Latin augur and auspex). Birds, it seems, continue to point to the future. By returning to the Victorian origins of the laws of thermodynamics, we can see how—and, perhaps, why—those laws have been broadly misconstrued and misapplied. In the 19th century, the first textbooks on the science of thermodynamics emerged from the work of Rudolf Clausius, in Berlin, as well as William Thomson (often called Lord Kelvin) and William Rankine, both in Glasgow. Studying how machines, such as steam engines, could exchange heat for mechanical work and vice-versa, these physicists learned of strict limits on efficiency. The best a machine could possibly do was to give up a small amount of energy as wasted heat. They also observed that if you had something that was hot on one side but cold on the other, the temperature would always even out. Their results were synthesized in the first two laws:

By returning to the Victorian origins of the laws of thermodynamics, we can see how—and, perhaps, why—those laws have been broadly misconstrued and misapplied. In the 19th century, the first textbooks on the science of thermodynamics emerged from the work of Rudolf Clausius, in Berlin, as well as William Thomson (often called Lord Kelvin) and William Rankine, both in Glasgow. Studying how machines, such as steam engines, could exchange heat for mechanical work and vice-versa, these physicists learned of strict limits on efficiency. The best a machine could possibly do was to give up a small amount of energy as wasted heat. They also observed that if you had something that was hot on one side but cold on the other, the temperature would always even out. Their results were synthesized in the first two laws: On 22 February 2002, Sgt Jacklean Davis was on a walk with her supervisor, Lt Samuel Lee, when Lee got a call from their commander at the seventh district in

On 22 February 2002, Sgt Jacklean Davis was on a walk with her supervisor, Lt Samuel Lee, when Lee got a call from their commander at the seventh district in