Mario Molina and Durwood Zaelke in Project Syndicate:

It is hard to imagine more devastating effects of climate change than the fires that have been raging in California, Oregon, and Washington, or the procession of hurricanes that have approached – and, at times, ravaged – the Gulf Coast. There have also been deadly heat waves in India, Pakistan, and Europe, and devastating flooding in Southeast Asia. But there is far worse ahead, with one risk, in particular, so great that it alone threatens humanity itself: the rapid depletion of Arctic sea ice.

It is hard to imagine more devastating effects of climate change than the fires that have been raging in California, Oregon, and Washington, or the procession of hurricanes that have approached – and, at times, ravaged – the Gulf Coast. There have also been deadly heat waves in India, Pakistan, and Europe, and devastating flooding in Southeast Asia. But there is far worse ahead, with one risk, in particular, so great that it alone threatens humanity itself: the rapid depletion of Arctic sea ice.

Recalling an Alfred Hitchcock movie, this climate “bomb” – which, at a certain point, could more than double the rate of global warming – has a timer that is being watched with growing anxiety. Each September, the extent of Arctic sea ice reaches its lowest level, before the lengthening darkness and falling temperatures cause it to begin to expand again. At this point, scientists compare its extent to previous years.

The results should frighten us all. This year, measurements from the National Snow and Ice Data Center in Boulder, Colorado show that there is less ice in the middle of the Arctic than ever before, and just-published research shows that winter sea ice in the Arctic’s Bering Sea hit its lowest level in 5,500 years in 2018 and 2019.

More here.

You will surely

You will surely  Spoon-benders are unlikely to be the only profession toasting the disappearance – supposing we rule out further hauntings – of Randi, who, being himself a brilliant magician as “The Amazing Randi: The Man No Jail Can Hold” (previously “The Great Randall: Telepath”) was repeatedly more effective than scientists at examining paranormalist claims, sometimes by simply performing their stunts himself.

Spoon-benders are unlikely to be the only profession toasting the disappearance – supposing we rule out further hauntings – of Randi, who, being himself a brilliant magician as “The Amazing Randi: The Man No Jail Can Hold” (previously “The Great Randall: Telepath”) was repeatedly more effective than scientists at examining paranormalist claims, sometimes by simply performing their stunts himself. Weathered, wiry and in his early 60s, the man stumbled into clinic, trailing cigarette smoke and clutching his chest. Over the previous week, he had had fleeting episodes of chest pressure but stayed away from the hospital. “I didn’t want to get the coronavirus,” he gasped as the nurses unbuttoned his shirt to get an EKG. Only when his pain had become relentless did he feel he had no choice but to come in. In pre-pandemic times, patients like him were routine at my Boston-area hospital; we saw them almost every day. But for much of the spring and summer, the halls and parking lots were eerily empty. I wondered if people were staying home and getting sicker, and I imagined that in a few months’ time these patients, once they became too ill to manage on their own, might flood the emergency rooms, wards and I.C.U.s, in a non-Covid wave. But more than seven months into the pandemic, there are still no lines of patients in the halls. While my colleagues and I are busier than we were in March, there has been no pent-up overflow of people with crushing chest pain, debilitating shortness of breath or fevers and wet, rattling coughs. But surprisingly, even months later, as coronavirus infection rates began falling and hospitals were again offering elective surgery and in-person visits to doctor’s offices, hospital admissions remained almost 20 percent lower than normal.

Weathered, wiry and in his early 60s, the man stumbled into clinic, trailing cigarette smoke and clutching his chest. Over the previous week, he had had fleeting episodes of chest pressure but stayed away from the hospital. “I didn’t want to get the coronavirus,” he gasped as the nurses unbuttoned his shirt to get an EKG. Only when his pain had become relentless did he feel he had no choice but to come in. In pre-pandemic times, patients like him were routine at my Boston-area hospital; we saw them almost every day. But for much of the spring and summer, the halls and parking lots were eerily empty. I wondered if people were staying home and getting sicker, and I imagined that in a few months’ time these patients, once they became too ill to manage on their own, might flood the emergency rooms, wards and I.C.U.s, in a non-Covid wave. But more than seven months into the pandemic, there are still no lines of patients in the halls. While my colleagues and I are busier than we were in March, there has been no pent-up overflow of people with crushing chest pain, debilitating shortness of breath or fevers and wet, rattling coughs. But surprisingly, even months later, as coronavirus infection rates began falling and hospitals were again offering elective surgery and in-person visits to doctor’s offices, hospital admissions remained almost 20 percent lower than normal. What’s it like to be a cat?

What’s it like to be a cat?  Timothy Larsen over at the LARB:

Timothy Larsen over at the LARB: Kathleen Tyson over at the Official Monetary and Financial Institutions Forum:

Kathleen Tyson over at the Official Monetary and Financial Institutions Forum: Gilad Edelman in Wired:

Gilad Edelman in Wired: Salomé Viljoen in Phenomenal World:

Salomé Viljoen in Phenomenal World: Raphaële Chappe and Mark Blyth debate Sebastian Mallaby in Foreign Affairs (registration required):

Raphaële Chappe and Mark Blyth debate Sebastian Mallaby in Foreign Affairs (registration required): “I have a crazy new way of writing poems,” John Berryman wrote to illustrator Ben Shahn in January 1956. He had indeed hit on something crazy and new: an 18-line structure he ended up calling his “

“I have a crazy new way of writing poems,” John Berryman wrote to illustrator Ben Shahn in January 1956. He had indeed hit on something crazy and new: an 18-line structure he ended up calling his “ W

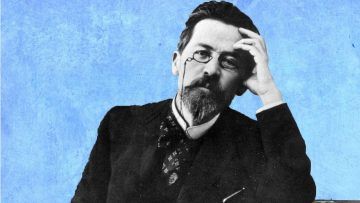

W No writer understood loneliness better than

No writer understood loneliness better than  Ah, election season. There’s a patriotic buzz in the air. Bumper stickers and lawn signs all over the neighborhood. Now comes the time when we check the location of our polling places, make a plan to vote—and pack a “go bag” in case we need to take to the streets in sustained mass protest to protect the integrity of the vote count. That last one is not something you’d expect to be doing in the United States, but things are different in the

Ah, election season. There’s a patriotic buzz in the air. Bumper stickers and lawn signs all over the neighborhood. Now comes the time when we check the location of our polling places, make a plan to vote—and pack a “go bag” in case we need to take to the streets in sustained mass protest to protect the integrity of the vote count. That last one is not something you’d expect to be doing in the United States, but things are different in the