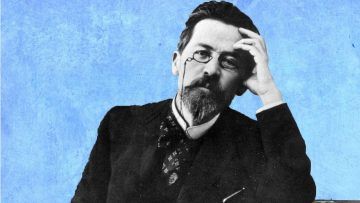

Gary Saul Morson in First Things:

No writer understood loneliness better than Chekhov. People long for understanding, and try to confide their feelings, but more often than not, others are too self-absorbed to care. In Chekhov’s plays, unlike those of his predecessors, characters speak past each other. Often enough, they talk in turn, but do not converse. Dunyasha, the maid in The Cherry Orchard, is eager to tell Anya, who has just arrived from abroad, that the clerk Yepikhodov proposed to her. Anya is too absorbed in her own memories to listen.

No writer understood loneliness better than Chekhov. People long for understanding, and try to confide their feelings, but more often than not, others are too self-absorbed to care. In Chekhov’s plays, unlike those of his predecessors, characters speak past each other. Often enough, they talk in turn, but do not converse. Dunyasha, the maid in The Cherry Orchard, is eager to tell Anya, who has just arrived from abroad, that the clerk Yepikhodov proposed to her. Anya is too absorbed in her own memories to listen.

Dunyasha: I’ve waited for you, my joy, my precious . . . I must tell you at once, I can’t wait another minute . . .

Anya: [listlessly] What?

Dunyasha: The clerk, Yepikhodov, proposed to me just after Easter.

Anya: You always talk about the same thing. . . . [Straightening her hair]. I’ve lost all my hairpins . . .

Dunyasha: I really don’t know what to think. He loves me—he loves me so!

Anya: [looking through the door into her room, tenderly] My, room, my windows. . . . I am home!

Chekhov’s audience cannot help thinking: If only we would enter into the feelings of others, life would be so much better.

In one early story, written before Chekhov imagined he could ever be a serious author, a cabman, Iona, tries time and time again to tell each of his fares about the death of his son, but everyone is in a hurry and no one pays any attention. He longs to share his grief, but he returns his horse to the stable as lonely as before. As the story ends, he at last addresses someone who appears to listen: his horse. “That’s how it is old girl,” he explains. “He went and died for no reason. . . .

Now suppose, you had a little colt, and you were own mother to that little colt. . . . And all at once that same little colt went and died. . . . You’d be sorry, wouldn’t you?” The story ends: “The little mare munches, listens, and breathes on her master’s hands. Iona is carried away and tells her all about it.”

More here.