Justin E. H. Smith in his Substack Newsletter:

You will recall that while I carried on and on about myself in the first missive, I also promised that in subsequent instalments the autobiographical dimension would fall away, and the person behind the writing would for the most appear only indirectly. And yet I have in the past weeks consistently inserted myself, the author, into every topic I have touched. Why do I keep doing this? Is this not a variety of self-absorption? And if so may we perhaps distinguish between vicious and virtuous instances of what is ordinarily taken to be an unmitigated vice?

You will recall that while I carried on and on about myself in the first missive, I also promised that in subsequent instalments the autobiographical dimension would fall away, and the person behind the writing would for the most appear only indirectly. And yet I have in the past weeks consistently inserted myself, the author, into every topic I have touched. Why do I keep doing this? Is this not a variety of self-absorption? And if so may we perhaps distinguish between vicious and virtuous instances of what is ordinarily taken to be an unmitigated vice?

I believe Jean-Jacques Rousseau can assist us in answering this question. I have been reading his Confessions these past weeks (completed in 1770, published posthumously in 1782), and have found this work surprisingly helpful for understanding Rousseau as a thinker. Over the years I’ve taught The Social Contract a number of times; I read La Nouvelle Héloïse (1761) a long time ago; and more recently, inspired by Pankaj Mishra’s interpretation of the dispute between Voltaire and Rousseau concerning national sovereignty and empire in Eastern Europe, I’ve had occasion to read the latter’s Considerations on the Government of Poland (1772).

I basically share Mishra’s view that Rousseau is a crucially important counter-Enlightenment figure before this tendency found its more familiar home in Germany, and that the debate with Voltaire over the fate of Poland is therefore key to understanding what has been at stake in numerous instances, over the subsequent centuries, of conflict between the pseudo-universalism of hegemons, on the one hand, and local demands for self-determination on the other, between the imposition of external power under the guise of an objective norm and the preservation of organic folk-ways. In this conflict, I generally have more sympathy for the side defended by Rousseau, and I take Voltaire to be a disgraceful apologist for imperialism.

More here.

The blob is a cloud of turbulence in a large water tank in the lab of the University of Chicago physicist

The blob is a cloud of turbulence in a large water tank in the lab of the University of Chicago physicist  The global pandemic has re-written the rules of global macroeconomic policy for us. We have witnessed significant monetary and fiscal policy innovation; growing unwillingness to accept that the design of stimulus should be independent of broader environmental and social goals; and a far more acute focus on the competence and scope of the State.

The global pandemic has re-written the rules of global macroeconomic policy for us. We have witnessed significant monetary and fiscal policy innovation; growing unwillingness to accept that the design of stimulus should be independent of broader environmental and social goals; and a far more acute focus on the competence and scope of the State. Will we be surprised again this November the way Americans were on Nov. 9, 2016 when they awoke to learn that reality TV star Donald Trump had been elected president? That outcome defied prognosticators and polls, and even Trump’s own expectation. “Oh, this is gonna be embarrassing,”

Will we be surprised again this November the way Americans were on Nov. 9, 2016 when they awoke to learn that reality TV star Donald Trump had been elected president? That outcome defied prognosticators and polls, and even Trump’s own expectation. “Oh, this is gonna be embarrassing,”  Arundhati Roy’s literary career has been one of a kind. Thrust into the limelight of the global publishing industry back in 1997 when her debut novel,

Arundhati Roy’s literary career has been one of a kind. Thrust into the limelight of the global publishing industry back in 1997 when her debut novel,  Urban Legends is a parabolic dish microphone pointed at history, collecting the waves that outsiders have bounced off the South Bronx. L’Official gathers representations of the South Bronx found in fiction, like Don DeLillo’s description of urban tourism in Underworld, and the ways it has been filtered through journalistic language. He proposes that classifications like “inner city” and the “ghetto” are also “versions of urban legends as well.” L’Official presents these ideas as euphemisms and “coded spatial signifiers for race,” which they are. In fact, the focus of Urban Legends is squarely on the views of those who never lived in the neighborhood. Very little of it touches on how the residents of the South Bronx represented themselves, and L’Official acknowledges this several times, best of all in the conclusion: “Though Urban Legends falls short of discussing ‘all kinds’ of artists, its aims were, and are, aligned with those of the Fort Apache Band, as articulated by Andy González: showing that art can, and does, emerge from an imperiled environment.” L’Official seems to know that hip-hop and graffiti don’t need his help at this point. He writes that graffiti artists in the South Bronx—“most of whom pointedly referred to themselves as writers—would no doubt tell you, graffiti was Bronx literature, and a populist form at that, which hardly required an agent or a publishing contract to reach an audience.”

Urban Legends is a parabolic dish microphone pointed at history, collecting the waves that outsiders have bounced off the South Bronx. L’Official gathers representations of the South Bronx found in fiction, like Don DeLillo’s description of urban tourism in Underworld, and the ways it has been filtered through journalistic language. He proposes that classifications like “inner city” and the “ghetto” are also “versions of urban legends as well.” L’Official presents these ideas as euphemisms and “coded spatial signifiers for race,” which they are. In fact, the focus of Urban Legends is squarely on the views of those who never lived in the neighborhood. Very little of it touches on how the residents of the South Bronx represented themselves, and L’Official acknowledges this several times, best of all in the conclusion: “Though Urban Legends falls short of discussing ‘all kinds’ of artists, its aims were, and are, aligned with those of the Fort Apache Band, as articulated by Andy González: showing that art can, and does, emerge from an imperiled environment.” L’Official seems to know that hip-hop and graffiti don’t need his help at this point. He writes that graffiti artists in the South Bronx—“most of whom pointedly referred to themselves as writers—would no doubt tell you, graffiti was Bronx literature, and a populist form at that, which hardly required an agent or a publishing contract to reach an audience.” IN HER 2007 BOOK, Awkward: A Detour, Mary Cappello posits the title state as a natural response to a world indifferent to our comfort or desires. “Awkwardness could be an effect of the rough handling of reality over which one has no control,” she proposes, and over the course of her wide-ranging, digressive, book-length essay, Cappello approaches the question of awkwardness from a variety of different angles. Melding memoir, literary and film criticism, etymological study, and many other modes, her book offers up a range of perspectives on and definitions of the state of awkwardness, all of which speak to the gap between our natural inclinations and the ways we are forced to adjust these inclinations to fit both a physical world and a social environment that routinely refutes them. “Each day on earth,” Cappello writes, “is at base an endless adjustment to there being too much or not enough, to there being something missing or something extra,” and it’s in this adjustment that awkwardness occurs.

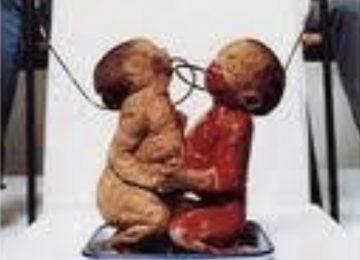

IN HER 2007 BOOK, Awkward: A Detour, Mary Cappello posits the title state as a natural response to a world indifferent to our comfort or desires. “Awkwardness could be an effect of the rough handling of reality over which one has no control,” she proposes, and over the course of her wide-ranging, digressive, book-length essay, Cappello approaches the question of awkwardness from a variety of different angles. Melding memoir, literary and film criticism, etymological study, and many other modes, her book offers up a range of perspectives on and definitions of the state of awkwardness, all of which speak to the gap between our natural inclinations and the ways we are forced to adjust these inclinations to fit both a physical world and a social environment that routinely refutes them. “Each day on earth,” Cappello writes, “is at base an endless adjustment to there being too much or not enough, to there being something missing or something extra,” and it’s in this adjustment that awkwardness occurs. There are two dead babies sitting in a medical pan inside a nondescript room. These babies face one another. Are they conjoined twins? There are tubes connected to the twin cadavers. A Chinese couple, a man and a woman, sit in chairs on either side of the babies. The tubes from the babies are connected to the arms of the couple. They are feeding their own blood into the mouths of the dead babies, who receive the elixir without discernible effect as the blood dribbles down their faces. It is a horrendous scene, made all the more horrendous by the fact that it is so compelling to look at, so fascinating to think about. Are these people trying to help the babies, connect with them somehow? Are they making fun of these dead babies or of the situation? Are we meant to laugh, cry, recoil in horror? What is this disturbing scene and why are we being subjected to it?

There are two dead babies sitting in a medical pan inside a nondescript room. These babies face one another. Are they conjoined twins? There are tubes connected to the twin cadavers. A Chinese couple, a man and a woman, sit in chairs on either side of the babies. The tubes from the babies are connected to the arms of the couple. They are feeding their own blood into the mouths of the dead babies, who receive the elixir without discernible effect as the blood dribbles down their faces. It is a horrendous scene, made all the more horrendous by the fact that it is so compelling to look at, so fascinating to think about. Are these people trying to help the babies, connect with them somehow? Are they making fun of these dead babies or of the situation? Are we meant to laugh, cry, recoil in horror? What is this disturbing scene and why are we being subjected to it? In the service of seeking truth, there would seem to be value in intellectual diversity, both in keeping ourselves honest and in the possibility of new ideas coming from unexpected quarters. That’s true in the natural sciences, but even more so in the humanities and social sciences, where the right/wrong distinction is sometimes less clear. But academia isn’t always diverse; as an empirical fact, there are a lot more liberals on university faculties than there are conservatives. I talk with Musa al-Gharbi about why this is true — self-selection? discrimination? — the extent to which it’s a real problem, and how we should better think about the value of diverse viewpoints.

In the service of seeking truth, there would seem to be value in intellectual diversity, both in keeping ourselves honest and in the possibility of new ideas coming from unexpected quarters. That’s true in the natural sciences, but even more so in the humanities and social sciences, where the right/wrong distinction is sometimes less clear. But academia isn’t always diverse; as an empirical fact, there are a lot more liberals on university faculties than there are conservatives. I talk with Musa al-Gharbi about why this is true — self-selection? discrimination? — the extent to which it’s a real problem, and how we should better think about the value of diverse viewpoints. At 7:47 a.m. on the Sunday of Memorial Day weekend, Dr. Jay Butler pounded out a grim email to colleagues at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta.

At 7:47 a.m. on the Sunday of Memorial Day weekend, Dr. Jay Butler pounded out a grim email to colleagues at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta. Today I am in Saddar, the former colonial center, clamorous and poetically falling to bits. Pakistan is a particularly loud country (“Well, yes,” a famous doctor once countered, rolling his eyes, “there are people here,” yet I stand by it), and Saddar is no different. Once a pedestrian zone crisscrossed by tram lines, it is now clogged by technicolor buses and auto-rickshaws, dusty vans, beat-up cars, or the tinted 4 x 4 of a Very Important Person, complete with armed bodyguards limply hanging off the side like party streamers. Traffic cops, elegant in starched white uniforms, stand bravely amidst the chaos to direct it with waving arms and screeching whistles. Saddar is home to the Karachi Press Club, the Cotton Exchange, the City Railway Station and, of course, the experiment in human ingenuity that is the parking lot outside the National Bank. Cars are parked in tight rows, squeezed into whatever available space, no sensible way to vacate. A smattering of biryani restaurants lines the far end of the lot. Dilawar (a young Pushtun with green eyes, a migrant from the cold north) hollers for the other “valets” and, consolidating their manpower, lift stationary cars out of the way, hooting encouragement, so I can reverse.

Today I am in Saddar, the former colonial center, clamorous and poetically falling to bits. Pakistan is a particularly loud country (“Well, yes,” a famous doctor once countered, rolling his eyes, “there are people here,” yet I stand by it), and Saddar is no different. Once a pedestrian zone crisscrossed by tram lines, it is now clogged by technicolor buses and auto-rickshaws, dusty vans, beat-up cars, or the tinted 4 x 4 of a Very Important Person, complete with armed bodyguards limply hanging off the side like party streamers. Traffic cops, elegant in starched white uniforms, stand bravely amidst the chaos to direct it with waving arms and screeching whistles. Saddar is home to the Karachi Press Club, the Cotton Exchange, the City Railway Station and, of course, the experiment in human ingenuity that is the parking lot outside the National Bank. Cars are parked in tight rows, squeezed into whatever available space, no sensible way to vacate. A smattering of biryani restaurants lines the far end of the lot. Dilawar (a young Pushtun with green eyes, a migrant from the cold north) hollers for the other “valets” and, consolidating their manpower, lift stationary cars out of the way, hooting encouragement, so I can reverse. Austria between the world wars fostered an extraordinary number of talents in diverse fields: Sigmund Freud in psychology, Arnold Schoenberg in music, Karl Kraus in journalism, Robert Musil in literature, Gustav Klimt in art, the Bauhaus in architecture, and the “Austrian school” in economics. In some of these areas, the overriding ethos was hostility to what the Bauhaus called “ornament.” The Vienna Circle of philosophers, led by Moritz Schlick, hoped to cleanse philosophy of anything vague or, to use their favorite term of abuse, “metaphysical.” Some members also aspired to provide firm foundations for knowledge, an ambition that can be traced back to Descartes and the 17th-century rationalists.

Austria between the world wars fostered an extraordinary number of talents in diverse fields: Sigmund Freud in psychology, Arnold Schoenberg in music, Karl Kraus in journalism, Robert Musil in literature, Gustav Klimt in art, the Bauhaus in architecture, and the “Austrian school” in economics. In some of these areas, the overriding ethos was hostility to what the Bauhaus called “ornament.” The Vienna Circle of philosophers, led by Moritz Schlick, hoped to cleanse philosophy of anything vague or, to use their favorite term of abuse, “metaphysical.” Some members also aspired to provide firm foundations for knowledge, an ambition that can be traced back to Descartes and the 17th-century rationalists. Cancer is a global health concern. There are over 100 types of cancer, which taken together, kill more than 10 million people across the world each year. Although localised cancers can be treated successfully through excision or localised radiotherapy, metastatic cancers spread throughout the body and are incurable, eventually leading to death. Once cancer cells have metastasised, they grow aggressively and are resistant to virtually all treatments. Despite enormous funds and dedicated efforts put into cancer research over the last half-century, half of all people diagnosed with cancer still die from their disease.

Cancer is a global health concern. There are over 100 types of cancer, which taken together, kill more than 10 million people across the world each year. Although localised cancers can be treated successfully through excision or localised radiotherapy, metastatic cancers spread throughout the body and are incurable, eventually leading to death. Once cancer cells have metastasised, they grow aggressively and are resistant to virtually all treatments. Despite enormous funds and dedicated efforts put into cancer research over the last half-century, half of all people diagnosed with cancer still die from their disease. On a chilly morning in February, about a thousand Chinese immigrants, Chinese Americans and others filled the streets of San Francisco’s historic Chinatown. They marched down Grant Avenue led by a bright red banner emblazoned with the words “Fight the Virus, NOT the People,” followed by Chinese text encouraging global collaboration to fight Covid-19 and condemning discrimination. Other signs carried by the crowd read: “Time For Science, Not Rumors” and “Reject Fear and Racism.” They were responding to incidents of bias and

On a chilly morning in February, about a thousand Chinese immigrants, Chinese Americans and others filled the streets of San Francisco’s historic Chinatown. They marched down Grant Avenue led by a bright red banner emblazoned with the words “Fight the Virus, NOT the People,” followed by Chinese text encouraging global collaboration to fight Covid-19 and condemning discrimination. Other signs carried by the crowd read: “Time For Science, Not Rumors” and “Reject Fear and Racism.” They were responding to incidents of bias and