Robert Simpson in Aeon:

Suppose you believe the state should look after the wellbeing of the poor and combat the structural forces that enrich the wealthy. Suppose you’re in a two-party electoral system, and that the party notionally aligned with your ideals made a Faustian pact with business elites to shore up the policies that perpetuate poverty – low minimum wages, tax incentives for rent-seekers, privatisation of public services, etc. What kind of ballot should you cast? You can’t vote for the party pushing things further to the Right. And if you don’t vote, or you vote for someone who’s almost certain not to win, you’re helping that same regressive party get elected. Yet lending your support to the ‘lesser of two evils’ candidate, whose platform you don’t really support, feels like an unacceptable compromise to your ideals.

Suppose you believe the state should look after the wellbeing of the poor and combat the structural forces that enrich the wealthy. Suppose you’re in a two-party electoral system, and that the party notionally aligned with your ideals made a Faustian pact with business elites to shore up the policies that perpetuate poverty – low minimum wages, tax incentives for rent-seekers, privatisation of public services, etc. What kind of ballot should you cast? You can’t vote for the party pushing things further to the Right. And if you don’t vote, or you vote for someone who’s almost certain not to win, you’re helping that same regressive party get elected. Yet lending your support to the ‘lesser of two evils’ candidate, whose platform you don’t really support, feels like an unacceptable compromise to your ideals.

The moral dilemma behind these scenarios is the subject of a well-known argument in moral philosophy. Bernard Williams argued that you should care about maintaining integrity in your personal ideals – not necessarily at all costs, but at least a bit. That’s because you have a special proprietary responsibility for acts you perform. Those choices and acts are, in some special sense, yours, distinct from outcomes that result from combining your choices and acts with everyone else’s.

More here.

The camera costs $58,990, including a 70mm lens made by Phase One partner Rodenstock. If you want the 23mm, 32mm or 50mm lenses, expect to pony up another $11,990 each. A

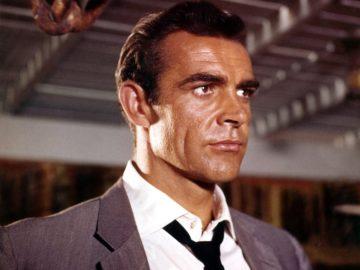

The camera costs $58,990, including a 70mm lens made by Phase One partner Rodenstock. If you want the 23mm, 32mm or 50mm lenses, expect to pony up another $11,990 each. A  Sean Connery

Sean Connery The American expat has enjoyed a storied position in culture and literature. In France, the role has been romanticized from Gene Kelly tap dancing his way through “An American in Paris” to Ernest Hemingway’s Paris-set “A Moveable Feast,” where he wrote, “There are only two places in the world where we can live happy: at home and in Paris.” Numbering around 250,000, Americans in France tend to lean Democratic and enjoy elite status, says Oleg Kobtzeff, an associate professor of international and comparative politics at the American University of Paris. “So Americans in France are themselves examples of soft power.” It’s not that they’ve been universally loved. Former President George W. Bush’s war on terror, including the Iraq War of 2003 that many allies condemned, made him as unpopular in France as President Trump is today.

The American expat has enjoyed a storied position in culture and literature. In France, the role has been romanticized from Gene Kelly tap dancing his way through “An American in Paris” to Ernest Hemingway’s Paris-set “A Moveable Feast,” where he wrote, “There are only two places in the world where we can live happy: at home and in Paris.” Numbering around 250,000, Americans in France tend to lean Democratic and enjoy elite status, says Oleg Kobtzeff, an associate professor of international and comparative politics at the American University of Paris. “So Americans in France are themselves examples of soft power.” It’s not that they’ve been universally loved. Former President George W. Bush’s war on terror, including the Iraq War of 2003 that many allies condemned, made him as unpopular in France as President Trump is today. Ben Railton in US Intellectual History Blog:

Ben Railton in US Intellectual History Blog: Samuel Clowes Huneke in Boston Review:

Samuel Clowes Huneke in Boston Review: Catherine Wilson in Aeon:

Catherine Wilson in Aeon: Robert Hockett in Forbes:

Robert Hockett in Forbes: For anyone with a platform,

For anyone with a platform,  The cable news talking heads seem obsessed with Joe Biden’s “significant” lead over Donald Trump in the national polls – as if this lead signifies a certain coming Biden victory in the presidential election. Also feeding the narrative that Biden is likely to win are stories and film clips of millions of Americans standing in long lines to vote early in record numbers.

The cable news talking heads seem obsessed with Joe Biden’s “significant” lead over Donald Trump in the national polls – as if this lead signifies a certain coming Biden victory in the presidential election. Also feeding the narrative that Biden is likely to win are stories and film clips of millions of Americans standing in long lines to vote early in record numbers. B

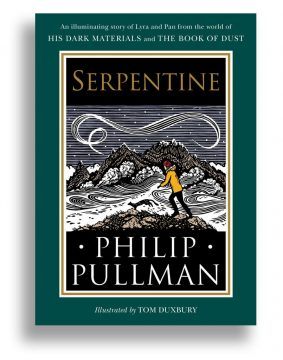

B Since the last volume of “His Dark Materials” appeared in 2000, Pullman has written two more (superb) volumes of a second trilogy called “

Since the last volume of “His Dark Materials” appeared in 2000, Pullman has written two more (superb) volumes of a second trilogy called “ ANTHONY DAVIS, winner of the

ANTHONY DAVIS, winner of the