Laura Trethewey in The Guardian:

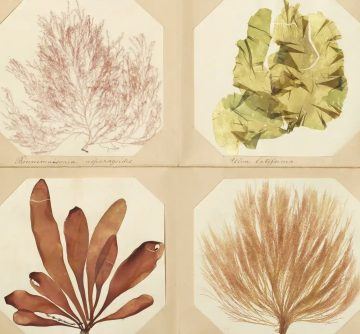

On his first day as the new science director for the Monterey Bay Aquarium in California in 2016, a giant blue storage locker caught Kyle Van Houtan’s eye. The locker was obscured by a dead ficus plant and looked as if no one had opened it for years. But the label on it intrigued him: Herbarium.

On his first day as the new science director for the Monterey Bay Aquarium in California in 2016, a giant blue storage locker caught Kyle Van Houtan’s eye. The locker was obscured by a dead ficus plant and looked as if no one had opened it for years. But the label on it intrigued him: Herbarium.

He opened it and inside found hundreds of stacked manila envelopes. Each one contained a single piece of seaweed, pressed and preserved on white paper.

The collection demonstrated a curator’s attention to detail, with neat labels in tidy handwriting that documented every seaweed’s origin and collector. And it gave Van Houtan and his colleague Emily Miller an idea.

More here.

Senator John Cornyn of Texas, locked in his own tight re-election race, recently told the local media that he, too, has disagreed with Mr. Trump on numerous issues, including deficit spending, trade policy and his raiding of the defense budget. Mr. Cornyn said he opted to keep his opposition private rather than get into a public tiff with Mr. Trump “because, as I’ve observed, those usually don’t end too well.”

Senator John Cornyn of Texas, locked in his own tight re-election race, recently told the local media that he, too, has disagreed with Mr. Trump on numerous issues, including deficit spending, trade policy and his raiding of the defense budget. Mr. Cornyn said he opted to keep his opposition private rather than get into a public tiff with Mr. Trump “because, as I’ve observed, those usually don’t end too well.” In Alysson Muotri’s laboratory, hundreds of miniature human brains, the size of sesame seeds, float in Petri dishes, sparking with electrical activity. These tiny structures, known as brain organoids, are grown from human stem cells and have become a familiar fixture in many labs that study the properties of the brain. Muotri, a neuroscientist at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD), has found some unusual ways to deploy his. He has connected organoids to walking robots, modified their genomes with Neanderthal genes, launched them into orbit aboard the International Space Station, and used them as models to develop more human-like artificial-intelligence systems. Like many scientists, Muotri has temporarily pivoted to studying COVID-19, using brain organoids to test

In Alysson Muotri’s laboratory, hundreds of miniature human brains, the size of sesame seeds, float in Petri dishes, sparking with electrical activity. These tiny structures, known as brain organoids, are grown from human stem cells and have become a familiar fixture in many labs that study the properties of the brain. Muotri, a neuroscientist at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD), has found some unusual ways to deploy his. He has connected organoids to walking robots, modified their genomes with Neanderthal genes, launched them into orbit aboard the International Space Station, and used them as models to develop more human-like artificial-intelligence systems. Like many scientists, Muotri has temporarily pivoted to studying COVID-19, using brain organoids to test  Back on planet Earth, in the show itself there is no limitless space-time, just a succession of powerful slabs of Nauman in which he swaps techniques, changes methods, explores materials, alternates moments of peace with bouts of heavy slapping, and never lets up in a madcap journey of artistic exploration usually set in darkness.

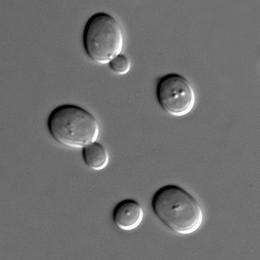

Back on planet Earth, in the show itself there is no limitless space-time, just a succession of powerful slabs of Nauman in which he swaps techniques, changes methods, explores materials, alternates moments of peace with bouts of heavy slapping, and never lets up in a madcap journey of artistic exploration usually set in darkness. In the past two decades, researchers have shown that biological traits in both species and individual cells can be shaped by the environment and inherited even without gene mutations, an outcome that contradicts one of the classical interpretations of Darwinian theory. But exactly how these epigenetic, or non-genetic, traits are inherited has been unclear. Now, in a study published Oct. 27 in the journal Cell Reports, Yale scientists show how

In the past two decades, researchers have shown that biological traits in both species and individual cells can be shaped by the environment and inherited even without gene mutations, an outcome that contradicts one of the classical interpretations of Darwinian theory. But exactly how these epigenetic, or non-genetic, traits are inherited has been unclear. Now, in a study published Oct. 27 in the journal Cell Reports, Yale scientists show how  In Search of the Soul presupposes less sympathy for religion on the part of its readers than Why Believe? and How to Believe do. Nonetheless, at just about the middle of the text, Cottingham proposes that “something like a traditional theistic worldview offer[s] a more hospitable framework” for the problems under consideration than does the “materialist consensus” among many philosophers and growing numbers of “nones.” Cottingham’s work consistently exhibits great respect for the findings of the sciences. As he bluntly writes in How to Believe, “there is no future for a religious or any other outlook that tries to contradict or set aside the findings of science.” “We must start from the nature of the universe as we find it,” he states in Why Believe?—and part of what we have found from the “spectacular success” of modern science is that there is “no possibility of a return to an animistic or mythological framework for understanding the world.” There are, however, limits to scientific explanation: most fundamentally, science cannot explain why the laws of nature are what they are. In David Hume’s words, modern science does not inquire into nature’s “ultimate springs and principles.” In Search of the Soul focuses on two problems that resist scientific explanation. First, the fact that “the conscious lifeworld of the individual subject,” though realized in and through the material properties of the human body, isn’t captured by an account of those properties (the “problem of consciousness”). And second, “the fact that moral values and obligations exert an authoritative demand on us, whether we like it or not” (what philosophers call the problem of “strong normativity”). For Cottingham, theism is an interpretive framework—a favorite phrase of his—that can accommodate those problems.

In Search of the Soul presupposes less sympathy for religion on the part of its readers than Why Believe? and How to Believe do. Nonetheless, at just about the middle of the text, Cottingham proposes that “something like a traditional theistic worldview offer[s] a more hospitable framework” for the problems under consideration than does the “materialist consensus” among many philosophers and growing numbers of “nones.” Cottingham’s work consistently exhibits great respect for the findings of the sciences. As he bluntly writes in How to Believe, “there is no future for a religious or any other outlook that tries to contradict or set aside the findings of science.” “We must start from the nature of the universe as we find it,” he states in Why Believe?—and part of what we have found from the “spectacular success” of modern science is that there is “no possibility of a return to an animistic or mythological framework for understanding the world.” There are, however, limits to scientific explanation: most fundamentally, science cannot explain why the laws of nature are what they are. In David Hume’s words, modern science does not inquire into nature’s “ultimate springs and principles.” In Search of the Soul focuses on two problems that resist scientific explanation. First, the fact that “the conscious lifeworld of the individual subject,” though realized in and through the material properties of the human body, isn’t captured by an account of those properties (the “problem of consciousness”). And second, “the fact that moral values and obligations exert an authoritative demand on us, whether we like it or not” (what philosophers call the problem of “strong normativity”). For Cottingham, theism is an interpretive framework—a favorite phrase of his—that can accommodate those problems.

A basic truth is once again trying to break through the agony of worldwide pandemic and the enduring inhumanity of racist oppression. Healthcare workers risking their lives for others, mutual aid networks empowering neighbourhoods, farmers delivering food to quarantined customers, mothers forming lines to protect youth from police violence: we’re in this life together. We – young and old, citizen and immigrant – do best when we collaborate. Indeed, our only way to survive is to have each other’s back while safeguarding the resilience and diversity of this planet we call home.

A basic truth is once again trying to break through the agony of worldwide pandemic and the enduring inhumanity of racist oppression. Healthcare workers risking their lives for others, mutual aid networks empowering neighbourhoods, farmers delivering food to quarantined customers, mothers forming lines to protect youth from police violence: we’re in this life together. We – young and old, citizen and immigrant – do best when we collaborate. Indeed, our only way to survive is to have each other’s back while safeguarding the resilience and diversity of this planet we call home. Erwin Schrödinger’s famous book What Is Life? highlighted the connections between physics, and thermodynamics in particular, and the nature of living beings. But the exact connections between living organisms and the flow of heat and entropy remains a topic of ongoing research. Jeremy England is a leader in this field, deriving connections between thermodynamic relations and the processes of life. He is also an ordained rabbi who finds resonances between modern science and passages in the Hebrew Bible. We talk about it all, from entropy fluctuation theorems to how scientists should approach religion.

Erwin Schrödinger’s famous book What Is Life? highlighted the connections between physics, and thermodynamics in particular, and the nature of living beings. But the exact connections between living organisms and the flow of heat and entropy remains a topic of ongoing research. Jeremy England is a leader in this field, deriving connections between thermodynamic relations and the processes of life. He is also an ordained rabbi who finds resonances between modern science and passages in the Hebrew Bible. We talk about it all, from entropy fluctuation theorems to how scientists should approach religion. Most Americans never encounter the simple, brute fact of U.S. military supremacy. Bases are far away; wars in remote places are waged remotely; amid the general fragmentation of social life, those who serve in the military are lumped into particular demographic niches. But on the rare occasions when Americans do think about their military, they are remarkably supportive. The military routinely ranks as the

Most Americans never encounter the simple, brute fact of U.S. military supremacy. Bases are far away; wars in remote places are waged remotely; amid the general fragmentation of social life, those who serve in the military are lumped into particular demographic niches. But on the rare occasions when Americans do think about their military, they are remarkably supportive. The military routinely ranks as the  By bringing attention to the very first encounters with uncertainty in early rabbinic literature (the Mishna and Tosefta), Halbertal insightfully demonstrates the ways in which early Jewish legal authorities were keenly interested in “demarcate[ing] and limit[ing] the destabilizing power of doubt and fear of uncertainty.” The heaps of laws surrounding states of uncertainty – which Halbertal correctly describes as some of the most complex areas of Jewish law – were not designed, by virtue of their sheer volume and complexity, to increase anxiety but to quell it. Early rabbinic engagement with doubt was thus an expression of liberation, not legal bondage. Its intent was not to compound hair-splitting laws on top of likely never-to-be-experienced hypotheticals for the sake of burdening Jews with laws where none previously existed, thereby adding to their already extensive repertoire of rules. Rather, this complex system was intended to free up the Jewish practitioner.

By bringing attention to the very first encounters with uncertainty in early rabbinic literature (the Mishna and Tosefta), Halbertal insightfully demonstrates the ways in which early Jewish legal authorities were keenly interested in “demarcate[ing] and limit[ing] the destabilizing power of doubt and fear of uncertainty.” The heaps of laws surrounding states of uncertainty – which Halbertal correctly describes as some of the most complex areas of Jewish law – were not designed, by virtue of their sheer volume and complexity, to increase anxiety but to quell it. Early rabbinic engagement with doubt was thus an expression of liberation, not legal bondage. Its intent was not to compound hair-splitting laws on top of likely never-to-be-experienced hypotheticals for the sake of burdening Jews with laws where none previously existed, thereby adding to their already extensive repertoire of rules. Rather, this complex system was intended to free up the Jewish practitioner. Susan Taubes’s fiction is animated by an unbearable awareness of death. Her first and only novel, Divorcing (1969), had the working title To America and Back in a Coffin. (An apt title, but deemed unmarketable and rejected by her publishers.) Like her contemporary Ingeborg Bachmann, Taubes’s fiction transposes existential mysteries with aesthetic ones. (There are other similarities between the pair: both published only one novel; both novels feature a love interest named Ivan; neither writer would live to see fifty.) Long out of print, Divorcing will finally be reissued by NYRB Classics this month. Taubes’s foreshortened oeuvre—this novel, an unpublished novella, a handful of stories—offers a range of formal precarities that mirror states of inward collapse. Fiction seemed to give shape to her own vulnerability. A lifelong depressive, she took her own life mere weeks after Divorcing was published. Her close friend Susan Sontag later suggested it was Hugh Kenner’s New York Times review that finally pushed Taubes over the edge. “Lady novelists have always claimed the privilege of transcending mere plausibilities,” he’d written. Sontag herself would identify the body.

Susan Taubes’s fiction is animated by an unbearable awareness of death. Her first and only novel, Divorcing (1969), had the working title To America and Back in a Coffin. (An apt title, but deemed unmarketable and rejected by her publishers.) Like her contemporary Ingeborg Bachmann, Taubes’s fiction transposes existential mysteries with aesthetic ones. (There are other similarities between the pair: both published only one novel; both novels feature a love interest named Ivan; neither writer would live to see fifty.) Long out of print, Divorcing will finally be reissued by NYRB Classics this month. Taubes’s foreshortened oeuvre—this novel, an unpublished novella, a handful of stories—offers a range of formal precarities that mirror states of inward collapse. Fiction seemed to give shape to her own vulnerability. A lifelong depressive, she took her own life mere weeks after Divorcing was published. Her close friend Susan Sontag later suggested it was Hugh Kenner’s New York Times review that finally pushed Taubes over the edge. “Lady novelists have always claimed the privilege of transcending mere plausibilities,” he’d written. Sontag herself would identify the body. In this didactic cultural moment, when many judge works of art by whether they deliver the right message with perfect clarity, it can be easy to forget that the purpose of novels is not to teach us life lessons or instill in us the proper view on some issue. In other words, the novel isn’t a tool of moral instruction. Rather, it’s a way to imagine how morality plays out in life, to experience vicariously how human beings—flawed, mercurial, riddled with contradictions they often don’t perceive themselves—try and fail not only to do the right thing, but even to understand what the right thing is in the first place. Sometimes that gap between our aspirations or self-knowledge and our actions can be tragic, but just as often, depending on your perspective, it can be funny.

In this didactic cultural moment, when many judge works of art by whether they deliver the right message with perfect clarity, it can be easy to forget that the purpose of novels is not to teach us life lessons or instill in us the proper view on some issue. In other words, the novel isn’t a tool of moral instruction. Rather, it’s a way to imagine how morality plays out in life, to experience vicariously how human beings—flawed, mercurial, riddled with contradictions they often don’t perceive themselves—try and fail not only to do the right thing, but even to understand what the right thing is in the first place. Sometimes that gap between our aspirations or self-knowledge and our actions can be tragic, but just as often, depending on your perspective, it can be funny. Christof Koch is a neuroscientist distinguished by his rock-solid scientific work and

Christof Koch is a neuroscientist distinguished by his rock-solid scientific work and  Will you please consider becoming a supporter of 3QD by

Will you please consider becoming a supporter of 3QD by  Founding editor of The Baffler and author of prophetic classics like Listen, Liberal and What’s the Matter with Kansas?, Thomas Frank skewers received wisdom across the political spectrum. In his new book, The People, No, Frank reveals that the Democratic Party has tied itself in knots about a phantom of its own making: populism. The original Populists—19th-century agitators for working people’s interests—spawned a revolving cast of journalists, intellectuals, and business interests determined to paint them as villainous xenophobic masses. These anti-populists have made the name of the movement into a dirty word. Today’s anti-populists equate the broad multiracial coalition of social-justice activists that supported Bernie Sanders with a very different alliance that championed Donald Trump in 2016.

Founding editor of The Baffler and author of prophetic classics like Listen, Liberal and What’s the Matter with Kansas?, Thomas Frank skewers received wisdom across the political spectrum. In his new book, The People, No, Frank reveals that the Democratic Party has tied itself in knots about a phantom of its own making: populism. The original Populists—19th-century agitators for working people’s interests—spawned a revolving cast of journalists, intellectuals, and business interests determined to paint them as villainous xenophobic masses. These anti-populists have made the name of the movement into a dirty word. Today’s anti-populists equate the broad multiracial coalition of social-justice activists that supported Bernie Sanders with a very different alliance that championed Donald Trump in 2016.