Niall Ferguson in the TLS:

In 2002 the Cambridge astrophysicist and Astronomer Royal Lord Rees predicted that, by the end of 2020, “bioterror or bioerror will lead to one million casualties in a single event”. In 2017 the Harvard psychologist Steven Pinker took the other side in a formal bet. As the terms of the wager defined casualties to include “victims requiring hospitalization”, Rees had already won long before the global death toll of Covid-19 passed the one million mark in September. Sadly for him, the stake was a meagre $400.

In 2002 the Cambridge astrophysicist and Astronomer Royal Lord Rees predicted that, by the end of 2020, “bioterror or bioerror will lead to one million casualties in a single event”. In 2017 the Harvard psychologist Steven Pinker took the other side in a formal bet. As the terms of the wager defined casualties to include “victims requiring hospitalization”, Rees had already won long before the global death toll of Covid-19 passed the one million mark in September. Sadly for him, the stake was a meagre $400.

Nicholas Christakis has given his rapidly written yet magisterial book about the pandemic the title Apollo’s Arrow. The allusion is to the plague the god unleashes against the Achaeans for kidnapping the daughter of his priest Chryses in Book One of Homer’s Iliad. An alternative title might have been Rees’s Bet. In a report from 1998 the US Department of Defense observed that “historians in the next millennium may find that the 20th century’s greatest fallacy was the belief that infectious diseases were nearing elimination”. Pinker was only one of many scholars who subscribed to this belief in the twenty-first century. “Disease outbreaks don’t become pandemics” any more, he argued in Enlightenment Now, because “advances in biology … make it easier for the good guys (and there are many more of them) to identify pathogens, invent antibiotics that overcome antibiotic resistance, and rapidly develop vaccines”.

Pinker was not alone in his complacency.

More here.

The 1990s now seem as distant as the 1950s. America is famously polarized into cultural tribes, each regarding the other with contempt and alarm. In the White House sits a populist entertainer with little evident commitment to constitutional norms. Sober scholars publish books with titles such as How Democracies Die

The 1990s now seem as distant as the 1950s. America is famously polarized into cultural tribes, each regarding the other with contempt and alarm. In the White House sits a populist entertainer with little evident commitment to constitutional norms. Sober scholars publish books with titles such as How Democracies Die  Silliness is not such a stretch as one would think, should one think of Wittgenstein. The ludic is at play, from conception, in the language-game itself; or the duck-rabbit as a vehicle of ambiguity, a perceptual “third thing,” a visual neologism: now ears … now beak, or “Both; not side-by-side, however, but about the one via the other.” Silliness is ruminative, i.e., we must look back over time for its sense to resonate. And it seeks a beyond. I consider the question of whether the two-headed calf should be counted as one animal or two—a serious moment for the Vatican Belvedere Gardens of 1625. Three, of course. “For the physicians, the feature distinguishing the individual was the brain; for followers of Aristotle, the heart,” wrote Carlo Ginzburg. And the dissection of the animal “was done with the aim of establishing not the ‘character’ peculiar to that particular animal, but ‘the common character’ … of the species as a whole.” A parallelism: Wittgenstein’s insistence that a student learn a new word by experiencing it through practice, being responsible to it and its usage, and eventually making the word meaningful for a greater understanding of her (whole) (linguistic) (yet shared, and seen) world.

Silliness is not such a stretch as one would think, should one think of Wittgenstein. The ludic is at play, from conception, in the language-game itself; or the duck-rabbit as a vehicle of ambiguity, a perceptual “third thing,” a visual neologism: now ears … now beak, or “Both; not side-by-side, however, but about the one via the other.” Silliness is ruminative, i.e., we must look back over time for its sense to resonate. And it seeks a beyond. I consider the question of whether the two-headed calf should be counted as one animal or two—a serious moment for the Vatican Belvedere Gardens of 1625. Three, of course. “For the physicians, the feature distinguishing the individual was the brain; for followers of Aristotle, the heart,” wrote Carlo Ginzburg. And the dissection of the animal “was done with the aim of establishing not the ‘character’ peculiar to that particular animal, but ‘the common character’ … of the species as a whole.” A parallelism: Wittgenstein’s insistence that a student learn a new word by experiencing it through practice, being responsible to it and its usage, and eventually making the word meaningful for a greater understanding of her (whole) (linguistic) (yet shared, and seen) world. When he died in 1677 at the age of forty-four, Spinoza left behind a compact Latin manuscript, Ethics, and his disciples quickly got it printed. It is a book like no other. It urges us to change our whole way of thinking and in particular to rid ourselves of the deep-rooted conceit that makes us imagine that our petty, transient lives might have some ultimate significance. The argument is dynamic, disruptive and upsetting, but it is contained within a literary framework of extraordinary austerity, comprising an array of definitions, axioms, propositions, proofs and scholia. The overall effect is not so much beautiful as sublime, like watching a massive fortress being shaken by storms and earthquakes. Many readers have found themselves deeply moved by Ethics but unable to say exactly what it means.

When he died in 1677 at the age of forty-four, Spinoza left behind a compact Latin manuscript, Ethics, and his disciples quickly got it printed. It is a book like no other. It urges us to change our whole way of thinking and in particular to rid ourselves of the deep-rooted conceit that makes us imagine that our petty, transient lives might have some ultimate significance. The argument is dynamic, disruptive and upsetting, but it is contained within a literary framework of extraordinary austerity, comprising an array of definitions, axioms, propositions, proofs and scholia. The overall effect is not so much beautiful as sublime, like watching a massive fortress being shaken by storms and earthquakes. Many readers have found themselves deeply moved by Ethics but unable to say exactly what it means.

Remarkably, in these fractious times, President Trump has managed to forge a singular area of consensus among liberals and conservatives, Republicans and Democrats: Nearly everyone seems to agree that he represents a throwback to a vintage version of manhood. After Mr. Trump proclaimed his “domination” over coronavirus, saluting Marine One and ripping off his mask, the Fox News host Greg Gutfeld cast the president in cinematic World War II terms — a tough-as-nails platoon leader who “put himself on the line” rather than abandon the troops. “He didn’t hide from the virus,”

Remarkably, in these fractious times, President Trump has managed to forge a singular area of consensus among liberals and conservatives, Republicans and Democrats: Nearly everyone seems to agree that he represents a throwback to a vintage version of manhood. After Mr. Trump proclaimed his “domination” over coronavirus, saluting Marine One and ripping off his mask, the Fox News host Greg Gutfeld cast the president in cinematic World War II terms — a tough-as-nails platoon leader who “put himself on the line” rather than abandon the troops. “He didn’t hide from the virus,”  American society is prone, political theorist Langdon Winner wrote in 2005, to “technological euphoria,” each bout of which is inevitably followed by a period of letdown and reassessment. Perhaps in part for this reason, reviewing the history of digital democracy feels like watching the same movie over and over again. Even Winner’s point has that quality: He first made it in the mid-eighties and has repeated it in every decade since. In the same vein, Warren Yoder, longtime director of the Public Policy Center of Mississippi, responded to the Pew survey by arguing that we have reached the inevitable “low point” with digital technology—as “has happened many times in the past with pamphleteers, muckraking newspapers, radio, deregulated television.” (“Things will get better,” Yoder cheekily adds, “just in time for a new generational crisis beginning soon after 2030.”)

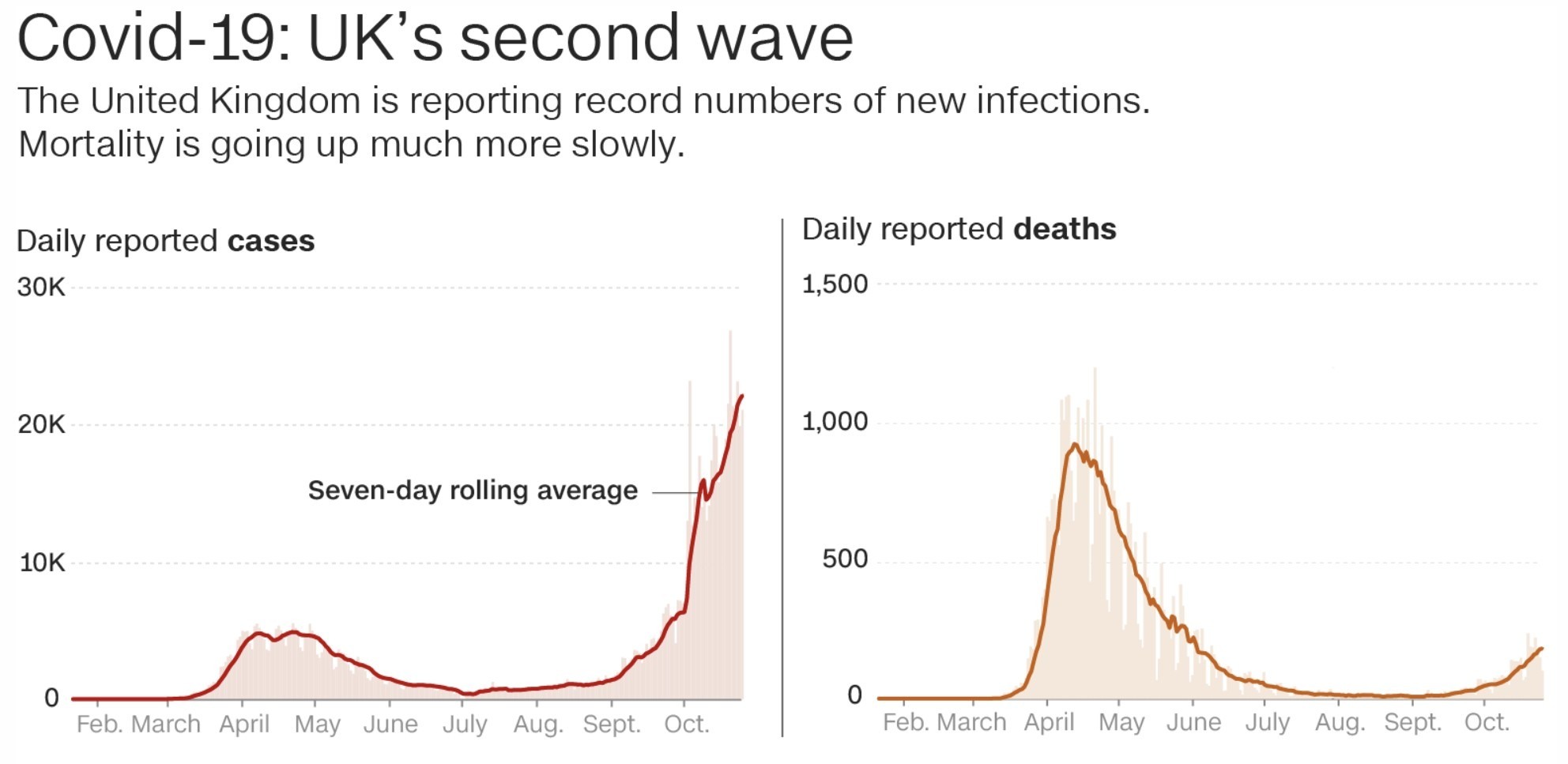

American society is prone, political theorist Langdon Winner wrote in 2005, to “technological euphoria,” each bout of which is inevitably followed by a period of letdown and reassessment. Perhaps in part for this reason, reviewing the history of digital democracy feels like watching the same movie over and over again. Even Winner’s point has that quality: He first made it in the mid-eighties and has repeated it in every decade since. In the same vein, Warren Yoder, longtime director of the Public Policy Center of Mississippi, responded to the Pew survey by arguing that we have reached the inevitable “low point” with digital technology—as “has happened many times in the past with pamphleteers, muckraking newspapers, radio, deregulated television.” (“Things will get better,” Yoder cheekily adds, “just in time for a new generational crisis beginning soon after 2030.”) Recent case and fatality figures from the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) show that while recorded Covid-19 cases are spiking in the United Kingdom, France, Spain, Germany and other European countries, deaths are not rising at the same rate.

Recent case and fatality figures from the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) show that while recorded Covid-19 cases are spiking in the United Kingdom, France, Spain, Germany and other European countries, deaths are not rising at the same rate.

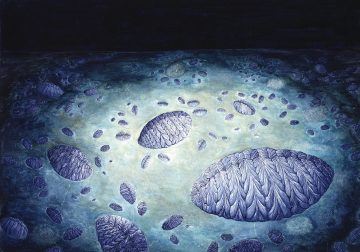

The revolutionary animal lived and died in the muck. In its final hours, it inched across the sea floor, leaving a track like a tyre print, and finally went still. Then geology set to work. Over the next half a billion years, sediment turned to stone, preserving the deathbed scene. The fossilized creature looks like a piece of frayed rope measuring just a few centimetres wide. But it was a trailblazer among living things. This was the earliest-known animal to show unequivocal evidence of two momentous innovations packaged together: the ability to roam the ocean floor, and a body built from segments. It was also among the oldest known to have clear front and back ends, and a left side that mirrored its right. Those same features are found today in animals from flies to flying foxes, from lobsters to lions.

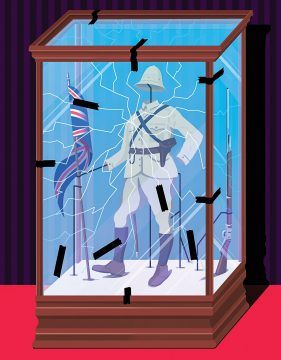

The revolutionary animal lived and died in the muck. In its final hours, it inched across the sea floor, leaving a track like a tyre print, and finally went still. Then geology set to work. Over the next half a billion years, sediment turned to stone, preserving the deathbed scene. The fossilized creature looks like a piece of frayed rope measuring just a few centimetres wide. But it was a trailblazer among living things. This was the earliest-known animal to show unequivocal evidence of two momentous innovations packaged together: the ability to roam the ocean floor, and a body built from segments. It was also among the oldest known to have clear front and back ends, and a left side that mirrored its right. Those same features are found today in animals from flies to flying foxes, from lobsters to lions. On a cloud-spackled Sunday last June, protesters in Bristol, England, gathered at a statue of Edward Colston, a seventeenth-century slave trader on whose watch more than eighty thousand Africans were trafficked across the Atlantic. “Pull it down!” the crowd chanted, as people yanked on a rope around the statue’s neck. A few tugs, and the figure clanged off its pedestal. A panel of its coat skirt cracked off to expose a hollow buttock as the demonstrators rolled the statue toward the harbor, a few hundred yards away, and then tipped it headlong into the water.

On a cloud-spackled Sunday last June, protesters in Bristol, England, gathered at a statue of Edward Colston, a seventeenth-century slave trader on whose watch more than eighty thousand Africans were trafficked across the Atlantic. “Pull it down!” the crowd chanted, as people yanked on a rope around the statue’s neck. A few tugs, and the figure clanged off its pedestal. A panel of its coat skirt cracked off to expose a hollow buttock as the demonstrators rolled the statue toward the harbor, a few hundred yards away, and then tipped it headlong into the water. And yet, despite his shifting placement in the dynamic force field of cultural politics, Steiner resisted turning into a curmudgeonly apologist for a world on the wane or allowing his Kulturpessimismus to sanction a resentful withdrawal from the public arena. In fact, one of the hallmarks of his career was a willingness to remain suspended within paradoxes, never forcing a simple choice between unpalatable options. This attitude was already evident in Language and Silence, which both celebrates humanistic high culture and acknowledges that the Holocaust has disabused us of the naïve illusion that it humanizes those who uphold it. Or as he put it in what is perhaps his most frequently cited sentences: “We come after. We know now that a man can read Goethe or Rilke in the evening, that he can play Bach or Schubert, and go to his day’s work at Auschwitz in the morning.”

And yet, despite his shifting placement in the dynamic force field of cultural politics, Steiner resisted turning into a curmudgeonly apologist for a world on the wane or allowing his Kulturpessimismus to sanction a resentful withdrawal from the public arena. In fact, one of the hallmarks of his career was a willingness to remain suspended within paradoxes, never forcing a simple choice between unpalatable options. This attitude was already evident in Language and Silence, which both celebrates humanistic high culture and acknowledges that the Holocaust has disabused us of the naïve illusion that it humanizes those who uphold it. Or as he put it in what is perhaps his most frequently cited sentences: “We come after. We know now that a man can read Goethe or Rilke in the evening, that he can play Bach or Schubert, and go to his day’s work at Auschwitz in the morning.”

Agatha Christie was in her mid-20s when, in 1916, she took up what seemed the improbable endeavor of penning her first detective novel. It was so unlikely, in fact, that her elder sister, Madge, with whom she had always competed, dared Agatha to accomplish the feat, certain of her sibling’s eventual failure.

Agatha Christie was in her mid-20s when, in 1916, she took up what seemed the improbable endeavor of penning her first detective novel. It was so unlikely, in fact, that her elder sister, Madge, with whom she had always competed, dared Agatha to accomplish the feat, certain of her sibling’s eventual failure.