Joseph Fridman in Aeon:

The machine they built is hungry. As far back as 2016, Facebook’s engineers could brag that their creation ‘ingests trillions of data points every day’ and produces ‘more than 6 million predictions per second’. Undoubtedly Facebook’s prediction engines are even more potent now, making relentless conjectures about your brand loyalties, your cravings, the arc of your desires. The company’s core market is what the social psychologist Shoshana Zuboff describes as ‘prediction products’: guesses about the future, assembled from ever-deeper forays into our lives and minds, and sold on to someone who wants to manipulate that future.

The machine they built is hungry. As far back as 2016, Facebook’s engineers could brag that their creation ‘ingests trillions of data points every day’ and produces ‘more than 6 million predictions per second’. Undoubtedly Facebook’s prediction engines are even more potent now, making relentless conjectures about your brand loyalties, your cravings, the arc of your desires. The company’s core market is what the social psychologist Shoshana Zuboff describes as ‘prediction products’: guesses about the future, assembled from ever-deeper forays into our lives and minds, and sold on to someone who wants to manipulate that future.

Yet Facebook and its peers aren’t the only entities devoting massive resources towards understanding the mechanics of prediction. At precisely the same moment in which the idea of predictive control has risen to dominance within the corporate sphere, it’s also gained a remarkable following within cognitive science. According to an increasingly influential school of neuroscientists, who orient themselves around the idea of the ‘predictive brain’, the essential activity of our most important organ is to produce a constant stream of predictions: predictions about the noises we’ll hear, the sensations we’ll feel, the objects we’ll perceive, the actions we’ll perform and the consequences that will follow. Taken together, these expectations weave the tapestry of our reality – in other words, our guesses about what we’ll see in the world become the world we see.

More here.

In his biggest policy announcement, he said the US government would end support for offensive operations in Yemen. That’s an important step, given the Saudi-led coalition’s disturbing pattern of using US precision weapons and intelligence to hit Yemeni civilian targets such as markets, funerals, and even a school bus. Trump closed his eyes to all that in the name of (illusory) US jobs. Biden rightfully will have nothing to do with it.

In his biggest policy announcement, he said the US government would end support for offensive operations in Yemen. That’s an important step, given the Saudi-led coalition’s disturbing pattern of using US precision weapons and intelligence to hit Yemeni civilian targets such as markets, funerals, and even a school bus. Trump closed his eyes to all that in the name of (illusory) US jobs. Biden rightfully will have nothing to do with it.

In “The Voice in Your Head,” a darkly comic short film by the writer-director Graham Parkes, a man wakes up every morning to find a fit, hipsterish dope perched next to his bed. “Good morning, fucko,” the dope says. “Ready for another disappointing day?” The camera follows the pair from the shower (“Your penis is very small”) to the car (“You know your dad hates you”) and then to work, where the dope, wearing a pin-striped olive jacket and gold chain, keeps the bit going through lunchtime. (“Eat normal.”) He’s a nuisance, a torment, and not especially original—the kind of bargain-bin hater that makes all the rest of us critics look bad.

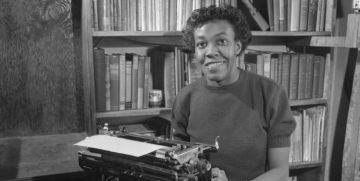

In “The Voice in Your Head,” a darkly comic short film by the writer-director Graham Parkes, a man wakes up every morning to find a fit, hipsterish dope perched next to his bed. “Good morning, fucko,” the dope says. “Ready for another disappointing day?” The camera follows the pair from the shower (“Your penis is very small”) to the car (“You know your dad hates you”) and then to work, where the dope, wearing a pin-striped olive jacket and gold chain, keeps the bit going through lunchtime. (“Eat normal.”) He’s a nuisance, a torment, and not especially original—the kind of bargain-bin hater that makes all the rest of us critics look bad. When it comes to pioneers in African American history,

When it comes to pioneers in African American history,  Eric Levitz in NY Magazine:

Eric Levitz in NY Magazine: Virginia Jackson and Meredith Martin in Avidly:

Virginia Jackson and Meredith Martin in Avidly: Jessica Boyall in Sidecar:

Jessica Boyall in Sidecar: Phenomenal World has releases its first collection

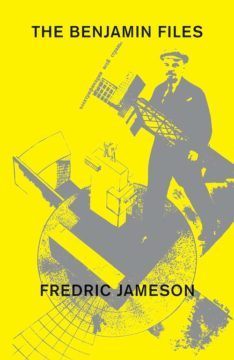

Phenomenal World has releases its first collection  Ian Balfour reviews The Benjamin Files by Fredric Jameson, in the LA Review of Books:

Ian Balfour reviews The Benjamin Files by Fredric Jameson, in the LA Review of Books: If I had stepped onstage at a metal concert in the late ’80s and announced to the audience that in the future they would be listening to all-synthesizer metal albums, I’d have had enough beer thrown at me to turn in my outfit for a bottle deposit. The metal and noise genres are reputed to be intrinsically rigid, but that’s what makes them so fun, so compelling and infuriating. Nowhere is this more evident than when surveying the totality of Aaron Turner’s work as an artist, musician, and founder of the heavy, influential, and (mostly) defunct label Hydra Head Records. Turner’s present band SUMAC—since its inception on a nonstop tear of activity, including a recent collaboration with Keiji Haino—just released May You Be Held, the latest planet on their horizon of metal.

If I had stepped onstage at a metal concert in the late ’80s and announced to the audience that in the future they would be listening to all-synthesizer metal albums, I’d have had enough beer thrown at me to turn in my outfit for a bottle deposit. The metal and noise genres are reputed to be intrinsically rigid, but that’s what makes them so fun, so compelling and infuriating. Nowhere is this more evident than when surveying the totality of Aaron Turner’s work as an artist, musician, and founder of the heavy, influential, and (mostly) defunct label Hydra Head Records. Turner’s present band SUMAC—since its inception on a nonstop tear of activity, including a recent collaboration with Keiji Haino—just released May You Be Held, the latest planet on their horizon of metal. In brief, the circumstances were these: Heine, a master of caustic wit and raw heartbreak, was in his early thirties and had found fame with his “Buch der Lieder” (“Book of Songs”), a collection of outwardly Romantic lyric poems with an ironic undertow that often escaped early readers. Platen bore a noble name—Count Platen-Hallermünde—but had grown up without financial advantages, serving in the military before turning to literature. He had won notice for finespun odes, sonnets, and adaptations of the Persian ghazal. Karl Immermann, a friend of Heine’s, had made cracks about pretentious poets who “vomit Ghaselen”; Heine quoted Immermann’s lines in one of his volumes of “Reisebilder” (“

In brief, the circumstances were these: Heine, a master of caustic wit and raw heartbreak, was in his early thirties and had found fame with his “Buch der Lieder” (“Book of Songs”), a collection of outwardly Romantic lyric poems with an ironic undertow that often escaped early readers. Platen bore a noble name—Count Platen-Hallermünde—but had grown up without financial advantages, serving in the military before turning to literature. He had won notice for finespun odes, sonnets, and adaptations of the Persian ghazal. Karl Immermann, a friend of Heine’s, had made cracks about pretentious poets who “vomit Ghaselen”; Heine quoted Immermann’s lines in one of his volumes of “Reisebilder” (“ JANUARY 6 WAS SUPPOSED

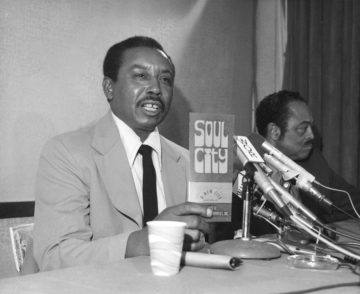

JANUARY 6 WAS SUPPOSED  Stop me if you’ve heard this one: A Black man walks into a federal government office and says, “Give me a lot of money and I’ll build you a Black city.” And the government, to everyone’s surprise, says, “OK, here’s $14 million!” No? Most people haven’t. The story of Floyd McKissick’s dream, struggle and, ultimately, failure to build an American city on behalf of Black citizens is one of the greatest least-told stories in American history. In “Soul City,” Thomas Healy chronicles this tragically quixotic enterprise by McKissick, a civil rights activist turned capitalist, who attempted, beginning in 1969, to build “Soul City,” a Black-run city on a former slave plantation in rural North Carolina, close to Southern Klan country.

Stop me if you’ve heard this one: A Black man walks into a federal government office and says, “Give me a lot of money and I’ll build you a Black city.” And the government, to everyone’s surprise, says, “OK, here’s $14 million!” No? Most people haven’t. The story of Floyd McKissick’s dream, struggle and, ultimately, failure to build an American city on behalf of Black citizens is one of the greatest least-told stories in American history. In “Soul City,” Thomas Healy chronicles this tragically quixotic enterprise by McKissick, a civil rights activist turned capitalist, who attempted, beginning in 1969, to build “Soul City,” a Black-run city on a former slave plantation in rural North Carolina, close to Southern Klan country.