Adrian Cho in Science:

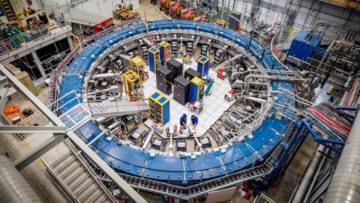

As early as March, the Muon g-2 experiment at Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory (Fermilab) will report a new measurement of the magnetism of the muon, a heavier, short-lived cousin of the electron. The effort entails measuring a single frequency with exquisite precision. In tantalizing results dating back to 2001, g-2 found that the muon is slightly more magnetic than theory predicts. If confirmed, the excess would signal, for the first time in decades, the existence of novel massive particles that an atom smasher might be able to produce, says Aida El-Khadra, a theorist at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. “This would be a very clear sign of new physics, so it would be a huge deal.”

As early as March, the Muon g-2 experiment at Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory (Fermilab) will report a new measurement of the magnetism of the muon, a heavier, short-lived cousin of the electron. The effort entails measuring a single frequency with exquisite precision. In tantalizing results dating back to 2001, g-2 found that the muon is slightly more magnetic than theory predicts. If confirmed, the excess would signal, for the first time in decades, the existence of novel massive particles that an atom smasher might be able to produce, says Aida El-Khadra, a theorist at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. “This would be a very clear sign of new physics, so it would be a huge deal.”

The measures that g-2 experimenters are taking to ensure they don’t fool themselves into claiming a false discovery are the stuff of spy novels, involving locked cabinets, sealed envelopes, and a second, secret frequency known to just two people, both outside the g-2 team. “My wife won’t pick me for responsible jobs like this, so I don’t know why an important experiment did,” says Joseph Lykken, Fermilab’s chief research officer, one of the keepers of the secret.

More here.

Countless academic articles and self-help books sing to the same tune – characterising immediate gratification as a short-sighted hitch while praising the virtues of long-term thinking as a means for overcoming temptation. Many people have heard of the marshmallow

Countless academic articles and self-help books sing to the same tune – characterising immediate gratification as a short-sighted hitch while praising the virtues of long-term thinking as a means for overcoming temptation. Many people have heard of the marshmallow  Years ago, when my body simply was what it was, soft and long, before I had even contemplated changing it into anything else, I came across Martin Schoeller’s Female Bodybuilders on a bookstore display table. In it were studio-lit portraits of women whose faces had been reduced to bone and socket and vein, whose skin had been stained with spray tan and eyes outlined in shadow. Enormous muscles rose up to enclose their necks. They looked prehistoric, fossilized and eternal. I thought they had destroyed their chances at love. My mistake was to assume they were living under the star of sexual capital, as I was. After all, they wore the rhinestones and velvet of showgirls. What I didn’t yet understand was that bodybuilders are ruled by a different star, the same star that would later rule me, if only temporarily. It was dim and solitary, with enormous gravity. I still don’t have a name for it.

Years ago, when my body simply was what it was, soft and long, before I had even contemplated changing it into anything else, I came across Martin Schoeller’s Female Bodybuilders on a bookstore display table. In it were studio-lit portraits of women whose faces had been reduced to bone and socket and vein, whose skin had been stained with spray tan and eyes outlined in shadow. Enormous muscles rose up to enclose their necks. They looked prehistoric, fossilized and eternal. I thought they had destroyed their chances at love. My mistake was to assume they were living under the star of sexual capital, as I was. After all, they wore the rhinestones and velvet of showgirls. What I didn’t yet understand was that bodybuilders are ruled by a different star, the same star that would later rule me, if only temporarily. It was dim and solitary, with enormous gravity. I still don’t have a name for it. IN 1527, THE VENETIAN EXPLORER

IN 1527, THE VENETIAN EXPLORER  Last week, my whole outlook on the world was transformed by a sheet of blank paper. Not just any paper, but beautifully embossed stationery, silky to the touch and decadent to write on. It was a gift from a dear friend and colleague. We collaborate over Zoom every week, so I could have thanked him on video, but instead I wrote a short note of gratitude and love, and posted it to him. His delight on receipt a few days later mirrored my own, and we shared a moment of emotional connection.

Last week, my whole outlook on the world was transformed by a sheet of blank paper. Not just any paper, but beautifully embossed stationery, silky to the touch and decadent to write on. It was a gift from a dear friend and colleague. We collaborate over Zoom every week, so I could have thanked him on video, but instead I wrote a short note of gratitude and love, and posted it to him. His delight on receipt a few days later mirrored my own, and we shared a moment of emotional connection. Massachusetts abolished enslavement

Massachusetts abolished enslavement

What is memory? I carried with me for more than forty years the distorted and etiolated memory-trace of what I believed was an anti-nuclear protest concert, held around 1979, somewhere in America, featuring James Taylor, Jackson Browne, Peter Frampton, and other stars of that long-forgotten era. Throughout all these decades I was convinced that the concert had been called “Nukes Knocks [sic] Your Socks Off”, or perhaps, alternatively, “Nukes Knocks Yer Sox Off”.

What is memory? I carried with me for more than forty years the distorted and etiolated memory-trace of what I believed was an anti-nuclear protest concert, held around 1979, somewhere in America, featuring James Taylor, Jackson Browne, Peter Frampton, and other stars of that long-forgotten era. Throughout all these decades I was convinced that the concert had been called “Nukes Knocks [sic] Your Socks Off”, or perhaps, alternatively, “Nukes Knocks Yer Sox Off”. It’s a truism that what we see about the world is a small fraction of all that exists. At the simplest level of physics and biology, our senses are drastically limited; we only see a narrow spectrum of electromagnetic waves, and we only hear a narrow band of sound. We don’t feel neutrinos or dark matter at all, even as they pass through our bodies, and we can’t perceive microscopic objects. While science can help us overcome some of these limitations, they do shape how we think about the world. Ziya Tong takes this idea and expands it to include the parts of our social and moral worlds that are effectively invisible to us — from where our food comes from to how we decide how wealth is allocated in society.

It’s a truism that what we see about the world is a small fraction of all that exists. At the simplest level of physics and biology, our senses are drastically limited; we only see a narrow spectrum of electromagnetic waves, and we only hear a narrow band of sound. We don’t feel neutrinos or dark matter at all, even as they pass through our bodies, and we can’t perceive microscopic objects. While science can help us overcome some of these limitations, they do shape how we think about the world. Ziya Tong takes this idea and expands it to include the parts of our social and moral worlds that are effectively invisible to us — from where our food comes from to how we decide how wealth is allocated in society. Our world has experienced diverging trends, leading to increased prosperity globally, while inequalities remain or increase. Democracies have expanded at the same time that nationalism and protectionism have seen a resurgence. Over the past decades, two major crises have disrupted our societies and weakened our common policy frameworks, casting doubt on our capacity to overcome shocks, address their root causes, and secure a better future for generations to come. They have also reminded us of how interdependent we are.

Our world has experienced diverging trends, leading to increased prosperity globally, while inequalities remain or increase. Democracies have expanded at the same time that nationalism and protectionism have seen a resurgence. Over the past decades, two major crises have disrupted our societies and weakened our common policy frameworks, casting doubt on our capacity to overcome shocks, address their root causes, and secure a better future for generations to come. They have also reminded us of how interdependent we are. I can tell you where it all started because I remember the moment exactly. It was late and I’d just finished the novel I’d been reading. A few more pages would send me off to sleep, so I went in search of a short story. They aren’t hard to come by around here; my office is made up of piles of books, mostly advance-reader copies that have been sent to me in hopes I’ll write a quote for the jacket. They arrive daily in padded mailers—novels, memoirs, essays, histories—things I never requested and in most cases will never get to. On this summer night in 2017, I picked up a collection called Uncommon Type, by Tom Hanks. It had been languishing in a pile by the dresser for a while, and I’d left it there because of an unarticulated belief that actors should stick to acting. Now for no particular reason I changed my mind. Why shouldn’t Tom Hanks write short stories? Why shouldn’t I read one? Off we went to bed, the book and I, and in doing so put the chain of events into motion. The story has started without my realizing it. The first door opened and I walked through.

I can tell you where it all started because I remember the moment exactly. It was late and I’d just finished the novel I’d been reading. A few more pages would send me off to sleep, so I went in search of a short story. They aren’t hard to come by around here; my office is made up of piles of books, mostly advance-reader copies that have been sent to me in hopes I’ll write a quote for the jacket. They arrive daily in padded mailers—novels, memoirs, essays, histories—things I never requested and in most cases will never get to. On this summer night in 2017, I picked up a collection called Uncommon Type, by Tom Hanks. It had been languishing in a pile by the dresser for a while, and I’d left it there because of an unarticulated belief that actors should stick to acting. Now for no particular reason I changed my mind. Why shouldn’t Tom Hanks write short stories? Why shouldn’t I read one? Off we went to bed, the book and I, and in doing so put the chain of events into motion. The story has started without my realizing it. The first door opened and I walked through. When

When  While Mary Wollstonecraft earned her place at the table for pioneering women in Judy Chicago’s art installation The Dinner Party (1974–9), she would not be everyone’s ideal guest. She has a reputation as an acerbic killjoy. She deemed novels to be the ‘spawn of idleness’. She did not embrace women in sisterhood but censured them for their propensity to ‘despise the freedom which they have not sufficient virtue to struggle to attain’. Wollstonecraft has proved both an inspiration and a challenge to those who have come after her.

While Mary Wollstonecraft earned her place at the table for pioneering women in Judy Chicago’s art installation The Dinner Party (1974–9), she would not be everyone’s ideal guest. She has a reputation as an acerbic killjoy. She deemed novels to be the ‘spawn of idleness’. She did not embrace women in sisterhood but censured them for their propensity to ‘despise the freedom which they have not sufficient virtue to struggle to attain’. Wollstonecraft has proved both an inspiration and a challenge to those who have come after her. Once upon a time, I thought that it was perfectly appropriate for restaurant workers to earn less than minimum wage. Tipping, in my view, was a means for customers to show gratitude and to reward a job well done. If I wanted to earn more as a restaurant worker, then I needed to hustle more, put more effort into my demeanor, and be a bit more charming.

Once upon a time, I thought that it was perfectly appropriate for restaurant workers to earn less than minimum wage. Tipping, in my view, was a means for customers to show gratitude and to reward a job well done. If I wanted to earn more as a restaurant worker, then I needed to hustle more, put more effort into my demeanor, and be a bit more charming. George Saunders, now in his early 60s, is a long-standing professor in the MFA Creative Writing program at Syracuse University’s College of Arts & Sciences. Widely recognized as one of the great living practitioners of the short story form, Saunders is a recipient of the MacArthur Fellowship and a winner of the Booker Prize for his first novel, 2017’s Lincoln in the Bardo. I conducted this interview at the end of 2020 in preparation for the release of his first nonfiction standalone title, A Swim in the Pond in the Rain, an eclectic and engrossing text that condenses the experience of workshopping with a master writer well-versed in instruction and invested in the continued development of his own reading acumen. I emailed George the questions, and he replied with alacrity, composing his answers in what I like to think of as the Nabokovian Strong Opinions mode.

George Saunders, now in his early 60s, is a long-standing professor in the MFA Creative Writing program at Syracuse University’s College of Arts & Sciences. Widely recognized as one of the great living practitioners of the short story form, Saunders is a recipient of the MacArthur Fellowship and a winner of the Booker Prize for his first novel, 2017’s Lincoln in the Bardo. I conducted this interview at the end of 2020 in preparation for the release of his first nonfiction standalone title, A Swim in the Pond in the Rain, an eclectic and engrossing text that condenses the experience of workshopping with a master writer well-versed in instruction and invested in the continued development of his own reading acumen. I emailed George the questions, and he replied with alacrity, composing his answers in what I like to think of as the Nabokovian Strong Opinions mode.