The Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory in Sci Tech Daily:

A novel computer algorithm, or set of rules, that accurately predicts the orbits of planets in the solar system could be adapted to better predict and control the behavior of the plasma that fuels fusion facilities designed to harvest on Earth the fusion energy that powers the sun and stars.

A novel computer algorithm, or set of rules, that accurately predicts the orbits of planets in the solar system could be adapted to better predict and control the behavior of the plasma that fuels fusion facilities designed to harvest on Earth the fusion energy that powers the sun and stars.

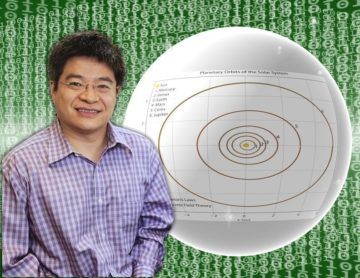

The algorithm, devised by a scientist at the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL), applies machine learning, the form of artificial intelligence (AI) that learns from experience, to develop the predictions. “Usually in physics, you make observations, create a theory based on those observations, and then use that theory to predict new observations,” said PPPL physicist Hong Qin, author of a paper detailing the concept in Scientific Reports. “What I’m doing is replacing this process with a type of black box that can produce accurate predictions without using a traditional theory or law.”

Qin (pronounced Chin) created a computer program into which he fed data from past observations of the orbits of Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, and the dwarf planet Ceres. This program, along with an additional program known as a “serving algorithm,” then made accurate predictions of the orbits of other planets in the solar system without using Newton’s laws of motion and gravitation. “Essentially, I bypassed all the fundamental ingredients of physics. I go directly from data to data,” Qin said. “There is no law of physics in the middle.”

More here. [Thanks to Ali Minai.]

With deft and bold action, Mario Draghi’s unity government in Italy can go some way toward addressing the COVID-19 emergency, laying the groundwork for long-term economic recovery, and restoring Italians’ confidence in their political leaders. But he cannot do it alone.

With deft and bold action, Mario Draghi’s unity government in Italy can go some way toward addressing the COVID-19 emergency, laying the groundwork for long-term economic recovery, and restoring Italians’ confidence in their political leaders. But he cannot do it alone. Tolstoy was a moralist. He wrote one novel—Anna Karenina—in which infidelity ends in death, and another—War and Peace—in which his characters endure a thousand pages of political, military and romantic turmoil so as to eventually earn the reward of domestic marital bliss. In the epilogue to War and Peace we encounter his protagonist Natasha, unrecognizably transformed. Throughout the main novel, we had known her as temperamental, beautiful and reflective; as independent, occasionally to the point of selfishness; as readily overwhelmed by ill-fated romantic passions.

Tolstoy was a moralist. He wrote one novel—Anna Karenina—in which infidelity ends in death, and another—War and Peace—in which his characters endure a thousand pages of political, military and romantic turmoil so as to eventually earn the reward of domestic marital bliss. In the epilogue to War and Peace we encounter his protagonist Natasha, unrecognizably transformed. Throughout the main novel, we had known her as temperamental, beautiful and reflective; as independent, occasionally to the point of selfishness; as readily overwhelmed by ill-fated romantic passions. In 2008, months before his election as president, Barack Obama assailed feckless black fathers who had reneged on responsibilities that ought not “to end at conception”. Where had all the black fathers gone, Obama wondered. In The New Jim Crow, Michelle Alexander has a simple answer to their whereabouts: they’ve gone to jail.

In 2008, months before his election as president, Barack Obama assailed feckless black fathers who had reneged on responsibilities that ought not “to end at conception”. Where had all the black fathers gone, Obama wondered. In The New Jim Crow, Michelle Alexander has a simple answer to their whereabouts: they’ve gone to jail.  On a trip to Warsaw, Poland, in 2019, Richard Freund confronted the history of resistance against the Nazis at a Holiday Inn. Freund, an archaeologist, and professor of Jewish Studies at Christopher Newport University in Virginia, was led by the hotel manager into the basement. “Lo and behold,” Freund says, a section of the Warsaw Ghetto wall was visible. Freund was in Warsaw accompanied by scientists from

On a trip to Warsaw, Poland, in 2019, Richard Freund confronted the history of resistance against the Nazis at a Holiday Inn. Freund, an archaeologist, and professor of Jewish Studies at Christopher Newport University in Virginia, was led by the hotel manager into the basement. “Lo and behold,” Freund says, a section of the Warsaw Ghetto wall was visible. Freund was in Warsaw accompanied by scientists from  Ross Andersen in The Atlantic:

Ross Andersen in The Atlantic: Judith Levine in Boston Review:

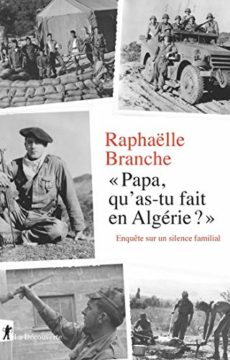

Judith Levine in Boston Review: Adam Shatz in the LRB:

Adam Shatz in the LRB: O

O Lee, or to be formal, Dame Hermione (she was awarded the title in 2013 for “services to literary scholarship”) is a leading member of that generation of British writers — it also includes Richard Holmes, Michael Holroyd, Jenny Uglow and Claire Tomalin — who have brought an infusion of style and imagination to the art of literary biography. She is probably most famous for her

Lee, or to be formal, Dame Hermione (she was awarded the title in 2013 for “services to literary scholarship”) is a leading member of that generation of British writers — it also includes Richard Holmes, Michael Holroyd, Jenny Uglow and Claire Tomalin — who have brought an infusion of style and imagination to the art of literary biography. She is probably most famous for her  Some people think libertarians only care about taxes and regulations. But I was asked not long ago, what’s the most important libertarian accomplishment in history? I said, “the abolition of slavery.”

Some people think libertarians only care about taxes and regulations. But I was asked not long ago, what’s the most important libertarian accomplishment in history? I said, “the abolition of slavery.” Released in the two-hundredth-anniversary year of the signing of the Declaration of Independence,

Released in the two-hundredth-anniversary year of the signing of the Declaration of Independence,