Adam Shatz in the LRB:

Adam Shatz in the LRB:

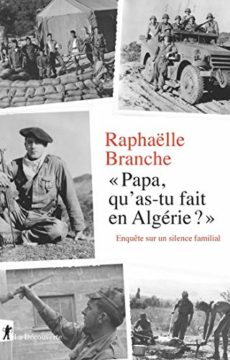

When Jacques Carbonnel went to Algeria to do his army service in 1956, his wife, Jeanne, asked him not to hide anything from her. ‘You want me to tell you everything,’ he wrote to her soon after arriving. ‘It’s ugly and you are too pretty. We arrest suspects, we release some, we kill some – it’s the dead runaways you see in the newspapers, phoney runaways! We push some out of helicopters above their villages. Criminal, inexcusable. The military solution doesn’t work here.’ Three days later, after returning from a two-day operation, he explained the method the army used to make suspected rebels talk: ‘We fill them up with water. We put a pipe in their mouths, in the anus, and we open the tap.’

Carbonnel was one of 1.5 million conscripts – appelés – who were sent to Algeria to defeat a nationalist uprising: an entire generation of young men in their early twenties. (The population of France in 1954 was 43.3 million.) But they were not at war, at least not officially. Algeria had been conquered in 1830 and administered as an integral part of France since 1848, when it was divided into three départements. More than a million European settlers lived there as French citizens. In Algeria the French were chez eux: according to a popular saying, the Mediterranean separated France from Algeria just as the Seine in Paris divided the Left Bank from the Right. When the rebels of the Front de Libération Nationale launched their war of independence in November 1954, France referred to them as hors-la-loi, outlaws rather than combatants. By the time Algeria won its independence in July 1962, hundreds of thousands of Algerians, and roughly 24,000 French soldiers, were dead. Algeria was liberated after more than a century of colonial domination, and France woke up to find itself stripped of its most prized imperial possession.

More here.